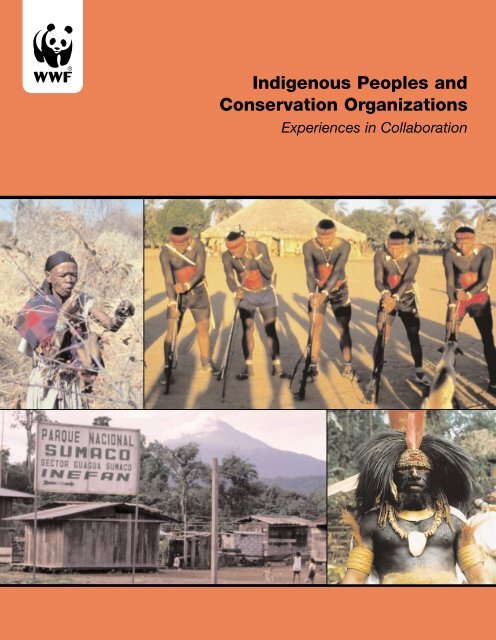

Indigenous Peoples and Conservation Organizations

Indigenous Peoples and Conservation Organizations

Indigenous Peoples and Conservation Organizations

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Organizations</strong><br />

Experiences in Collaboration

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Organizations</strong><br />

Experiences in Collaboration<br />

Ron Weber, John Butler, <strong>and</strong> Patty Larson, Editors<br />

February 2000

Support for this publication was provided by the Biodiversity Support Program, the Ford Foundation, <strong>and</strong><br />

World Wildlife Fund.<br />

The Biodiversity Support Program (BSP) is a consortium of World Wildlife Fund, The Nature<br />

Conservancy, <strong>and</strong> World Resources Institute, funded by the United States Agency for International<br />

Development (USAID). This publication was made possible through support provided to BSP by the<br />

Global Bureau of USAID, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number DHR-5554-A-00-8044-00.<br />

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors <strong>and</strong> do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.<br />

Typography <strong>and</strong> layout by Williams Production Group

CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

Preface<br />

iv<br />

v<br />

Part One: Introduction<br />

Chapter 1 <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> 3<br />

Chapter 2 <strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships with <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> 7<br />

Part Two: Case Studies<br />

Chapter 3 <strong>Indigenous</strong> Federations <strong>and</strong> the Market:<br />

The Runa of Napo, Ecuador Dominique Irvine 21<br />

Chapter 4 Lessons in Collaboration: The Xavante/WWF<br />

Wildlife Management Project in Central Brazil Laura R. Graham 47<br />

Chapter 5 Holding On to the L<strong>and</strong>: The Long Journey of the<br />

Sirionó Indians of Eastern Lowl<strong>and</strong> Bolivia Wendy R. Townsend 73<br />

Chapter 6 WWF’s Partnership with the Foi of Lake Kutubu,<br />

Papua New Guinea Joe Regis 91<br />

Chapter 7 Environmental Governance: Lessons from the Ju/’hoan<br />

Bushmen in Northeastern Namibia Barbara Wyckoff-Baird 113<br />

Part Three: Conclusions<br />

Chapter 8 Signposts for the Road Ahead 139<br />

Contributors 147<br />

Annex. <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong>: WWF Statement of Principles 149

iv<br />

Acknowledgments<br />

The editors would like to thank the case study authors, whose work forms the core of this book, for<br />

their dedication to carefully documenting project experiences so that others can learn from them.<br />

Thanks also go to participants in WWF’s 1998 workshop on collaboration with indigenous peoples for<br />

sharing their firsth<strong>and</strong> knowledge to help identify approaches to effective collaboration. This book<br />

would not have come to fruition without the long-term commitment, advice, <strong>and</strong> contributions of Janis<br />

Alcorn, Bronwen Golder, Gonzalo Oviedo, Femy Pinto, Kirsten Silvius, Stephanie Thullen, Margaret<br />

Williams, Diane Wood, <strong>and</strong> Sejal Worah. Special appreciation goes to Barbara Wyckoff-Baird, who<br />

coordinated the development of the case studies <strong>and</strong> played a lead role in designing the 1998 workshop.<br />

Last, but not least, we thank the initiative’s funders—the Ford Foundation; <strong>Peoples</strong>, Forests <strong>and</strong> Reefs,<br />

a USAID-funded program of the Biodiversity Support Program; <strong>and</strong> World Wildlife Fund—for seeing<br />

the importance of sharing lessons <strong>and</strong> guidelines for improving collaborative efforts between conservation<br />

organizations <strong>and</strong> indigenous peoples.

v<br />

Preface<br />

Each day, more <strong>and</strong> more of the world’s species are losing their toeholds on the future. As cities <strong>and</strong><br />

agricultural l<strong>and</strong>s spread, wildlife habitats are increasingly enveloped <strong>and</strong> erased by the exp<strong>and</strong>ing rings<br />

of modern human activity. At the margins of these circles of change, in the last remaining remnants of<br />

tropical forests, grassl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> pristine coasts, live isolated peoples with traditional ties to their l<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> waters. <strong>Indigenous</strong> people inhabit over 85 percent of the world’s protected areas. New proposed<br />

protected areas almost invariably include areas claimed as indigenous territories. In some countries,<br />

more biodiversity is found in indigenous reserves than in nature preserves. And so it is that, at the end of<br />

the twentieth century, conservationists are urgently seeking ways to collaborate with indigenous peoples<br />

to preserve biodiversity <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong> wildlife habitats for the future.<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong>ists have found that such collaboration is not always easy—either locally at the level of<br />

communities or regionally at the level of federations. Collaboration remains a work in progress.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> groups are suspicious that conservationists intend to alienate their l<strong>and</strong>s from them. While<br />

traditional resource management <strong>and</strong> value systems generally support conservation objectives, indigenous<br />

communities often lack people with expertise for monitoring biodiversity levels <strong>and</strong> planning l<strong>and</strong><br />

use that is compatible with habitat maintenance. They sometimes lack the organizational capacity to<br />

interact with outsiders or to manage project funds. They face multiple problems that accompany modernization.<br />

They usually have very little political weight at the national level <strong>and</strong> are sometimes viewed<br />

as troublemakers by national governments. At the international level, however, indigenous peoples are<br />

increasingly asserting their right to be recognized as conservation partners, <strong>and</strong> conservation NGOs<br />

increasingly find indigenous interests represented in stakeholder groups.<br />

There is a critical need to strengthen the ability <strong>and</strong> rights of indigenous peoples to manage biodiversity<br />

<strong>and</strong> find productive avenues for working with conservation NGOs. Donors increasingly recognize this<br />

<strong>and</strong> are responding by providing technical assistance to indigenous resource managers, strengthening the<br />

capacity of indigenous groups to communicate effectively with outside NGOs <strong>and</strong> government agencies,<br />

<strong>and</strong> supporting appropriate policy reforms. Yet insufficient attention has been paid to sharing the lessons<br />

NGOs have learned from their efforts to collaborate with indigenous peoples.<br />

World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) project experiences can provide lessons for all conservation groups, <strong>and</strong><br />

foster a broader underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the implications of applying WWF’s 1996 statement of principles for<br />

working with indigenous peoples. While the case studies in this volume review efforts designed with<br />

more limited objectives than the new ecoregional initiatives WWF is moving toward, the lessons about<br />

collaboration with indigenous communities remain valid. And while the meaning of indigenous differs<br />

in Asia, Africa, <strong>and</strong> Latin America, <strong>and</strong> the degree of self-identification as indigenous peoples varies<br />

within regions, the general lessons <strong>and</strong> insights from WWF field experiences can be applied globally in<br />

all types of conservation initiatives involving marginalized ethnic minorities.<br />

I hope that the lessons from this first-ever review of WWF’s engagement with indigenous communities<br />

will be widely read, <strong>and</strong> integrated into the operational guidelines of conservation organizations <strong>and</strong><br />

agencies around the world.<br />

Janis B. Alcorn<br />

Director, <strong>Peoples</strong>, Forests & Reefs Program<br />

Biodiversity Support Program, Washington, D.C.

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><br />

In The Diversity of Life, biologist Edward O.<br />

Wilson notes that five cataclysmic “spasms of<br />

extinction” from meteorite collisions, climatic<br />

changes, <strong>and</strong> other natural events have swept like<br />

scythes through the biosphere during the past 600<br />

million years. He postulates that a sixth great<br />

cycle of extinction is now under way, this one<br />

caused entirely by humans. Perhaps one-fifth of<br />

the world’s biodiversity will vanish by the year<br />

2020 if current trends persist.<br />

Less well known is another cycle of extinctions<br />

that parallels the one presently sweeping through<br />

the biosphere. Traditional societies, with their<br />

rich cultural heritage <strong>and</strong> historical link to nature,<br />

are vanishing at a rate unmatched in recorded<br />

history, <strong>and</strong> as many as half of those that remain<br />

are expected to disappear in the first 100 years of<br />

the new millennium.<br />

It only takes a glance at a map to show why conservationists<br />

should be concerned—biodiversity<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultural diversity are highly correlated. If<br />

one uses language as an indicator of cultural<br />

diversity, then six of the nine countries that<br />

account for 60 percent of all human languages<br />

are also areas of biological “megadiversity”<br />

teeming with plant <strong>and</strong> animal species so numerous<br />

a multitude remains uncounted. In terms of<br />

biomass, tropical rain forests are known to be the<br />

richest <strong>and</strong> most varied habitats on the planet.<br />

They are also the most culturally diverse regions,<br />

home to as many as half the world’s more than<br />

4,000 indigenous peoples.<br />

This is significant because, until recently, most<br />

of these peoples lived in relative harmony with<br />

their environments, using <strong>and</strong> managing their<br />

resource bases sustainably. The environmental<br />

alterations made by indigenous groups, such as<br />

the Bentian Dayak rattan farmers of<br />

Kalimantaan, were so subtle, in fact, that outsiders<br />

have mistakenly presumed vast stretches<br />

of the Earth to be wildernesses barren of human<br />

populations. The movement to establish<br />

national parks <strong>and</strong> reserves that began at the<br />

turn of the twentieth century was intended to<br />

keep at least a representative portion of these<br />

areas pristine, removed from human predation<br />

as the pace of technology <strong>and</strong> economic development<br />

accelerated. By the last quarter of the<br />

century it became clear in much of the world<br />

that this idea had serious flaws. <strong>Conservation</strong>ists<br />

who persuaded the state to establish<br />

protected areas found many of these victories to<br />

be hollow. Government agencies often lacked<br />

either the political will or the manpower, skills,<br />

<strong>and</strong> funding to defend park boundaries from<br />

outside encroachment.

4 <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><br />

By the 1980s, some conservation organizations<br />

began to develop new strategies designed to turn<br />

local communities into allies of park conservation.<br />

Some approaches focused on creating rings<br />

of low-intensity development around parks that<br />

would act as barriers to colonization by migrant<br />

farmers who practiced slash-<strong>and</strong>-burn agriculture.<br />

Others focused on projects that more actively<br />

involved local populations in managing wildlife<br />

<strong>and</strong> other resources in ways that gave them a tangible<br />

stake in preserving habitat not only around<br />

but in protected areas. Sustainable development<br />

that merged income generation <strong>and</strong> conservation<br />

became a new watchword.<br />

WWF published a book about its experiences<br />

during a decade of work with rural communities<br />

in integrated conservation <strong>and</strong> development<br />

projects (Larson et al. 1996). Valuable lessons<br />

were learned that are being applied in working<br />

with communities around the world. Yet this<br />

field experience also suggested that the rural<br />

poor are far from monolithic, varying not only<br />

from country to country, but within national<br />

borders. In fact, many of the projects involved<br />

populations that were marginalized from the<br />

mainstream by language <strong>and</strong> culture as well as<br />

class <strong>and</strong> income. And it became increasingly<br />

evident that these groups were not intruders to<br />

wilderness ecosystems but integral parts of<br />

them. Indeed, in many places national reserves<br />

<strong>and</strong> parks had been carved out of their traditional<br />

territories. <strong>Conservation</strong>ists were in danger<br />

of adding to the misery of the world’s most<br />

disenfranchised peoples. WWF responded by<br />

drafting a policy statement respecting the<br />

integrity <strong>and</strong> rights of traditional peoples <strong>and</strong><br />

establishing guidelines for its relations with<br />

them (see Annex).<br />

It became apparent that working with indigenous<br />

communities involves complex issues that pose<br />

new challenges but also open up new opportunities.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples are in many ways more<br />

organized <strong>and</strong> better able to represent their own<br />

interests <strong>and</strong> make their case to outsiders than<br />

ever before. <strong>Indigenous</strong> groups around the world<br />

have established more than a thous<strong>and</strong> grass-roots<br />

organizations to enhance their livelihoods <strong>and</strong><br />

gain greater control of their l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> resources<br />

(Hitchcock 1994). Many indigenous groups are<br />

politically active <strong>and</strong> play an important role in<br />

influencing national <strong>and</strong> international environmental<br />

<strong>and</strong> sustainable development policies.<br />

At the same time, these communities st<strong>and</strong> at a<br />

crossroads <strong>and</strong> confront an uncertain future. If<br />

many indigenous groups once lived in relative<br />

balance with their environments, that equation has<br />

been severely disrupted. <strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples face<br />

mounting pressures from the outside as encroachment<br />

by agribusiness, by petroleum, mineral, <strong>and</strong><br />

timber combines, <strong>and</strong> by uprooted, l<strong>and</strong>less farmers<br />

shrinks traditional territories. They also face a<br />

growing internal challenge as their population<br />

densities increase <strong>and</strong> the market economy undermines<br />

subsistence strategies <strong>and</strong> the cultural traditions<br />

that supported them. <strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples are<br />

not only in danger of losing their l<strong>and</strong> but the<br />

identity the l<strong>and</strong> gave them. They are increasingly<br />

under pressure to augment rates of resource<br />

extraction to unsustainable levels. If they resist<br />

doing so, someone else is ready to argue for the<br />

right to do so—<strong>and</strong> the state, starved for funds, is<br />

often more than ready to listen.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> groups that have maintained close<br />

contact with the l<strong>and</strong> know it well. Where cultures<br />

<strong>and</strong> traditional resource management practices<br />

remain relatively intact, they often have<br />

mechanisms for dealing with resource scarcity or<br />

other changes in the natural resource base, but<br />

have limited means for assessing the side effects<br />

of new technologies or new kinds of exploitation.<br />

A potential role for conservation organizations is<br />

to help indigenous groups obtain relevant legal,<br />

scientific, <strong>and</strong> economic information, weigh their<br />

options, <strong>and</strong> select strategies that are appropriate.<br />

This is more complicated than it seems, since<br />

many traditional peoples face the dual challenge<br />

of organizing themselves institutionally, first to<br />

claim legal title to their l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> second to manage<br />

the l<strong>and</strong> wisely.<br />

In looking at the issue of conservation <strong>and</strong><br />

indigenous peoples, two key questions emerge:<br />

What are the common concerns of conservation<br />

organizations <strong>and</strong> indigenous peoples? How can<br />

they collaborate effectively?<br />

To better underst<strong>and</strong> the issues involved, WWF’s<br />

Latin America <strong>and</strong> Caribbean Program (LAC)<br />

decided in 1996 to survey its experience working<br />

with indigenous peoples. From a decade of<br />

funding, 35 projects were identified that had at<br />

least one component related to indigenous peo-

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> 5<br />

ple. These projects ranged from efforts in<br />

Mexico <strong>and</strong> Central America that involved the<br />

Maya, Miskito, <strong>and</strong> Kuna Indians, to efforts in<br />

South America with a wide variety of indigenous<br />

groups in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador,<br />

Chile, Argentina, <strong>and</strong> Bolivia.<br />

The spectrum of project activities has been as<br />

broad as the geographic distribution was wide.<br />

Support has been provided for training, educational,<br />

<strong>and</strong> capacity-building efforts. Some projects<br />

focused entirely on a specific issue of<br />

interest to an indigenous group, such as the<br />

Xavante’s concern about declining wildlife populations<br />

on their homel<strong>and</strong> in central Brazil.<br />

Other efforts, such as the Pacaya–Samiria project<br />

in Peru, included indigenous people as stakeholders<br />

in larger integrated conservation <strong>and</strong> development<br />

projects. Over time, WWF gathered<br />

experience at working with indigenous organizations<br />

that ranged in size from village associations<br />

to regional federations, <strong>and</strong> national <strong>and</strong> even<br />

transnational confederations. All of these projects<br />

contributed to WWF’s growing underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

of the need for meaningful partnerships with<br />

indigenous peoples on conservation <strong>and</strong> natural<br />

resource management at the community, national,<br />

<strong>and</strong> international levels.<br />

In collaboration with WWF’s People <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> Program, LAC decided to select<br />

several case studies for in-depth review <strong>and</strong> augment<br />

them with case studies from other areas of<br />

the globe to identify common processes <strong>and</strong> lessons<br />

that could help guide future project activity.<br />

Respected experts in conservation <strong>and</strong> development<br />

who were closely involved with the communities<br />

<strong>and</strong> projects being profiled were asked<br />

to prepare the case studies. They were asked to<br />

examine how conservation organizations collaborated<br />

with indigenous groups to develop a common<br />

agenda <strong>and</strong> strengthen local capacity to<br />

implement it, <strong>and</strong> how this process affected project<br />

results. A workshop brought together field<br />

staff from four regional programs within WWF<br />

to discuss the studies <strong>and</strong> bring their own experiences<br />

to bear in analyzing issues that had been<br />

spotlighted. An overview of the history <strong>and</strong> situation<br />

of indigenous peoples worldwide, presented<br />

at the workshop, is included here to provide a<br />

contextual lens that readers can use to bring individual<br />

cases into sharper focus.<br />

The structure of this book mirrors the process of<br />

its formation. The overview concludes Part One.<br />

Part Two contains the five case studies that form<br />

the book’s core. Part Three discusses common<br />

themes <strong>and</strong> closes with a look ahead at how lessons<br />

might be applied.<br />

Although the sample of case studies is small,<br />

taken together they suggest how human cultures<br />

have mirrored the richness <strong>and</strong> diversity of the<br />

natural environments that helped shape them.<br />

Although they are from different parts of the<br />

world <strong>and</strong> involve peoples who would have great<br />

difficulty speaking to one another directly, the<br />

experiences in one locale often throw light on<br />

efforts in the other case studies to locally manage<br />

resources vital to community survival. Chapter 3<br />

examines an attempt to selectively harvest, plane,<br />

<strong>and</strong> market wood products for export by<br />

Quichua-speaking communities in an oil-rich<br />

area of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Chapter 4 presents<br />

an effort in Brazil by outsiders <strong>and</strong> a<br />

Western-educated Xavante leader to process <strong>and</strong><br />

market native fruits, <strong>and</strong> contrasts it with a project<br />

to manage subsistence game harvests which<br />

has helped spark a cultural revival <strong>and</strong> engage<br />

the broader community. Chapter 5 looks at the<br />

Sirionó Indians of eastern Bolivia, who have battled<br />

back from the verge of extinction to win a<br />

territory, <strong>and</strong> now must develop a resource management<br />

plan to hold on to it. Chapter 6 examines<br />

how subsistence fisheries management is<br />

taking hold among the Foi people of Lake<br />

Kutubu in Papua New Guinea (PNG), one of the<br />

crown jewels of world biodiversity. Chapter 7<br />

explores how the Ju/’hoan Bushmen in northeastern<br />

Namibia are working with government planners<br />

to adapt traditional resource management<br />

systems, invent new institutional structures, <strong>and</strong><br />

develop ecotourism in the Kalahari Desert.<br />

Readers should keep in mind two sets of issues.<br />

The first set is internal to indigenous groups <strong>and</strong><br />

involves questions about cultural intactness, institutional<br />

capacity, <strong>and</strong> the mix of subsistence <strong>and</strong><br />

cash economies. Issues about l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong><br />

usage rights are central here. The second set of<br />

issues is external <strong>and</strong> concerns the kind <strong>and</strong><br />

degree of involvement by outside actors. Two of<br />

the case studies, for example, involve nearby<br />

national parks, but government policies in the<br />

two cases are polar opposites, shedding light on

6 <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><br />

the difference it makes when the state encourages<br />

rather than discourages community involvement<br />

in managing natural resources. Another example<br />

is petroleum development. In the case of Napo,<br />

Ecuador, local communities are scrambling to<br />

cope with the side effects of unbridled development<br />

by multinational firms in partnership with<br />

the state. In PNG, a petroleum consortium is trying<br />

to minimize its intrusiveness <strong>and</strong> share the<br />

benefits of newfound wealth with local communities.<br />

One might also note the role that tenure<br />

plays in the two cases, since indigenous peoples<br />

in PNG enjoy customary ownership <strong>and</strong> usage<br />

rights unparalleled in most areas of the world.<br />

A final example is the role conservation organizations,<br />

particularly WWF, played in these case studies.<br />

In some, WWF was a peripheral collaborator<br />

in a cobbled-together coalition. In others its goal<br />

was to be an active partner. Sometimes, this difference<br />

reflected a disparity in resources between<br />

partners whose primary focus was socioeconomic<br />

development <strong>and</strong> those whose long-term focus<br />

was conservation. Other times, it reflected where<br />

a project fell on WWF’s learning curve. The<br />

Brazil <strong>and</strong> Ecuador projects, for instance, date<br />

from WWF’s first experiences with communitybased<br />

conservation <strong>and</strong> development, while the<br />

examples from PNG <strong>and</strong> Namibia began later <strong>and</strong><br />

benefited from what was learned before.<br />

Lessons from the case studies are also relevant to<br />

new conservation contexts. During the past two<br />

years, WWF <strong>and</strong> other conservation organizations<br />

have widened their focus to target conservation<br />

resources on ecoregions—large geographic<br />

areas that contain tightly integrated sets of<br />

ecosystems <strong>and</strong> important ecological interactions<br />

<strong>and</strong> evolutionary mechanisms that generate <strong>and</strong><br />

maintain species. The new strategy grows out of<br />

heightened concern that successfully protecting<br />

isolated patches of wilderness <strong>and</strong> specific<br />

species is not enough to ward off accelerating<br />

threats to the planet’s biodiversity. A new scale<br />

of thinking, planning, <strong>and</strong> acting is needed to<br />

meet the scale of the biological challenge.<br />

Collaboration of diverse stakeholders is a primary<br />

strategy for achieving these ambitious goals<br />

(Dinerstein et al. 1999). Examples of emerging<br />

partnerships with indigenous peoples <strong>and</strong> other<br />

issues involved in working at this larger scale are<br />

provided in the conclusion.<br />

References<br />

Dinerstein, Eric, George Powell, David Olson,<br />

Eric Wikramanayake, Robin Abell, Colby<br />

Loucks, Emma Underwood, Tom Allnut, Wes<br />

Wettengel, Taylor Ricketts, Neil Burgess, Sheila<br />

O’Connor, Holly Str<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Melody Mobley.<br />

1999. Workbook for Conducting Biological<br />

Assessments <strong>and</strong> Developing Diversity Visions<br />

for Ecoregion-Based <strong>Conservation</strong>, Part I:<br />

Terrestrial Ecoregions. Washington, D.C.: World<br />

Wildlife Fund.<br />

Hitchcock, Robert K. 1994. Endangered<br />

<strong>Peoples</strong>: <strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights <strong>and</strong> the Environment.<br />

Colorado Journal of International Environmental<br />

Law <strong>and</strong> Policy 5 (1):11.<br />

Larson, Patricia S., Mark Freudenberger, <strong>and</strong><br />

Barbara Wyckoff-Baird. 1996. WWF Integrated<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> Development Projects.<br />

Washington, D.C.: World Wildlife Fund.<br />

Wilson, Edward O. 1992. The Diversity of Life.<br />

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

CHAPTER 2<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships with<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><br />

To form effective partnerships, one must know<br />

one’s partners well. In the case of indigenous<br />

peoples, this poses special problems. The populations<br />

are so diverse <strong>and</strong> their marginalization so<br />

deep in many cases that outsiders frequently lack<br />

a clear picture of whom exactly they are working<br />

with. This chapter reviews the terminology in<br />

order to explain why these groups are important<br />

to conservation of global biodiversity. It then<br />

reviews the broader policy <strong>and</strong> programmatic<br />

context in which indigenous peoples <strong>and</strong> conservation<br />

organizations are interacting. It closes by<br />

examining how WWF approaches its work with<br />

indigenous peoples, <strong>and</strong> profiles issues that other<br />

conservation groups are likely to face as they<br />

take on similar activities.<br />

I. A Global Overview<br />

1.1 Defining What <strong>Indigenous</strong> Means<br />

Given their diverse histories, cultures, <strong>and</strong><br />

locales, it is not surprising that no single term<br />

completely encompasses the people who are the<br />

focus of this book. Officially, WWF uses the<br />

definition (or “statement of coverage”) of the<br />

International Labour Organization (ILO) in<br />

Convention 169—Concerning <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

Tribal <strong>Peoples</strong> in Independent Countries. 1<br />

According to ILO (1998):<br />

The term indigenous refers to those who,<br />

while retaining totally or partially their traditional<br />

languages, institutions, <strong>and</strong><br />

lifestyles which distinguish them from the<br />

dominant society, occupied a particular<br />

area before other population groups<br />

arrived. This is a description which is<br />

valid in North <strong>and</strong> South America, <strong>and</strong> in<br />

some areas of the Pacific. In most of the<br />

world, however, there is very little distinction<br />

between the time at which tribal <strong>and</strong><br />

other traditional peoples arrived in the<br />

region <strong>and</strong> the time at which other populations<br />

arrived. In Africa, for instance, there<br />

is no evidence to indicate that the Maasai,<br />

the Pygmies or the San (Bushmen),<br />

namely peoples who have distinct social,<br />

economic <strong>and</strong> cultural features, arrived in<br />

the region they now inhabit long before<br />

other African populations. The same is<br />

true in some parts of Asia. The ILO therefore<br />

decided, when it first began working<br />

intensively on these questions shortly after<br />

World War II, that it should refer to indigenous<br />

<strong>and</strong> tribal peoples. The intention was<br />

to cover a social situation, rather than to<br />

establish a priority based on whose ancestors<br />

had arrived in a particular area first.<br />

In addition, the description of certain

8 <strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships<br />

population groups as tribal is more easily<br />

accepted by some governments than a<br />

description of those peoples as indigenous.<br />

Another term that has become relevant for biodiversity<br />

conservation since the Convention on<br />

Biological Diversity came into force is that of<br />

“local communities embodying traditional<br />

lifestyles,” or “traditional peoples” for short.<br />

This term has a socioeconomic as well as a cultural<br />

dimension. It usually implies a largely subsistence<br />

economy based on close ties to the l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

International organizations that are working with<br />

indigenous peoples, such as the UN Working<br />

Group on <strong>Indigenous</strong> Populations, the World<br />

Bank, <strong>and</strong> the European Union, have identified<br />

the following characteristics of indigenous peoples<br />

relative to natural resource management:<br />

• ancestral attachment to l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> resources;<br />

• management of relatively large territories<br />

or areas;<br />

• collective rights over resources;<br />

• traditional systems of control, use, <strong>and</strong><br />

management of l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> resources;<br />

• traditional institutions <strong>and</strong> leadership<br />

structures for self-governance <strong>and</strong><br />

decision making;<br />

• systems for benefit sharing;<br />

• traditional ecological knowledge; <strong>and</strong><br />

• subsistence economies that are largely selfsufficient<br />

<strong>and</strong> rely on resource diversity<br />

rather than monocultures or simplified<br />

ecosystems.<br />

The question for conservation organizations is<br />

whether these characteristics apply as well to traditional<br />

rural peoples, mainly in Asia, Africa, <strong>and</strong><br />

Latin America, who generally are not called or<br />

don’t call themselves “indigenous.” In Latin<br />

America, for example, this question can be asked<br />

about Afro–Latin American groups like the<br />

Maroons of Suriname, the black communities of<br />

the Chocó forests, <strong>and</strong> the Garífunas of Central<br />

America. If, generally speaking, these groups<br />

share most of the characteristics listed above, an<br />

essential difference between traditional <strong>and</strong><br />

indigenous peoples has been the latter’s claimed<br />

right to political self-determination, based on a<br />

distinct identity <strong>and</strong> culture <strong>and</strong> often on prior<br />

occupation. This distinction, however, is also<br />

blurring since traditional peoples often have distinctive<br />

cultures that marginalize them from<br />

mainstream society, <strong>and</strong> many ethnolinguistic<br />

communities around the world are claiming the<br />

right to political self-determination.<br />

In many cases, the primary difference between<br />

indigenous <strong>and</strong> traditional peoples may be one of<br />

aboriginality to the place in question, particularly<br />

in cases where colonialism has uprooted <strong>and</strong> dispossessed<br />

indigenous peoples. Aboriginality, in<br />

many legal systems, can be used to support<br />

claims to limited sovereignty, a right that the<br />

occupying power sometimes has implicitly<br />

acknowledged through the signing of treaties.<br />

Until recently, these rights have remained latent,<br />

<strong>and</strong> aboriginal peoples have faced a Hobson’s<br />

choice between cultural assimilation <strong>and</strong> remaining<br />

wards of the state. When indigenous peoples<br />

are able to establish these rights legally, they<br />

have an important power that traditional peoples<br />

often lack: the power to say “no” to outsiders,<br />

whether they are conservationists or developers.<br />

For WWF’s conservation work, the differences<br />

between indigenous <strong>and</strong> traditional peoples are<br />

far less important than the similarities. Therefore<br />

WWF policies that refer to indigenous peoples<br />

refer also to tribal peoples, <strong>and</strong> by extension to<br />

traditional peoples.<br />

1.2 Population Estimates <strong>and</strong> Distribution<br />

Using ILO Convention 169’s definition, there are<br />

some 300 million men, women, <strong>and</strong> children<br />

worldwide who can be called “indigenous <strong>and</strong><br />

tribal” people living within the borders of independent<br />

nation states in North <strong>and</strong> South America,<br />

Northern Europe, Asia, Africa, <strong>and</strong> Oceania. The<br />

l<strong>and</strong> they occupy spans a wide geographical range,<br />

including the polar regions, northern <strong>and</strong> southern<br />

deserts, <strong>and</strong> tropical savannas <strong>and</strong> forests.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples account for 4,000 to 5,000 of<br />

the nearly 7,000 spoken languages, representing<br />

much of humankind’s cultural diversity. They<br />

include groups as disparate as the Quechua from<br />

Bolivia, Ecuador, <strong>and</strong> Peru, who collectively number<br />

more than 10 million people, <strong>and</strong> the tiny b<strong>and</strong><br />

of Gurumalum in Papua New Guinea who number<br />

fewer than 10 individuals (IUCN 1997, 30).<br />

Although these groups account for only about 6<br />

percent of the world’s population (Hitchcock<br />

1994), they live in areas of vital importance to

<strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships 9<br />

conservationists. Alan Durning (1992) notes that<br />

“the vast majority of the world’s biological diversity<br />

... is in l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> seascapes inhabited<br />

<strong>and</strong> used by local peoples, mostly indigenous.”<br />

This is reflected in the correlation between linguistic<br />

diversity <strong>and</strong> biodiversity. Of the nine<br />

countries that account for 60 percent of all human<br />

languages, six are also centers of biodiversity that<br />

contain immense numbers of plant <strong>and</strong> animal<br />

species (see figure 2.1). Ten of the 12 megacenters<br />

for biodiversity listed in figure 2.1 can be<br />

found among the 25 countries containing the<br />

largest numbers of endemic languages (see lists<br />

2.1 <strong>and</strong> 2.2). Bio-rich tropical rain forests are<br />

also culturally diverse, containing about 2,000<br />

indigenous peoples, nearly half the world’s total.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples are linked with the l<strong>and</strong> they<br />

occupy through highly sophisticated resource<br />

management practices. Most “wildernesses,”<br />

especially those that currently are sparsely populated,<br />

are not pristine (Gomez-Pompa <strong>and</strong> Kaus<br />

1992). Many seemingly untouched l<strong>and</strong>scapes are<br />

actually cultural l<strong>and</strong>scapes, either created or<br />

modified by humans through natural forest management,<br />

cultivation, or the use of fire. According<br />

to a Canadian indigenous peoples’ organization,<br />

the Four Directions Council (1996), “the territories<br />

in which indigenous peoples traditionally live are<br />

shaped environments, with biodiversity as a<br />

priority goal, notwithst<strong>and</strong>ing the fact that the<br />

modifications may be subtle <strong>and</strong> can be confused<br />

with the natural evolution of the l<strong>and</strong>scape.”<br />

WWF International’s People <strong>and</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong><br />

Unit has conducted an analysis that supports these<br />

views. It superimposed maps of WWF’s 200 priority<br />

ecoregions around the world onto maps showing<br />

the distribution of indigenous cultures. The<br />

results show a significant overlap of cultural <strong>and</strong><br />

biological diversity (see table 2.1). Although the<br />

analysis is not yet complete, preliminary results<br />

confirm the importance of indigenous peoples <strong>and</strong><br />

their issues for scaling up conservation efforts.<br />

1.3 Threats, Vulnerability, <strong>and</strong><br />

Marginalization<br />

Tragically, <strong>and</strong> despite their contributions to<br />

biodiversity conservation <strong>and</strong> to human culture,<br />

indigenous societies are disappearing at an unprecedented<br />

pace. Approximately 10 percent of<br />

existing indigenous languages are nearly extinct,<br />

endangering the cultures of hundreds of peoples.<br />

Among countries facing the highest rates of language<br />

extinction are Australia with 138 <strong>and</strong> the<br />

United States with 67. During the next century, at<br />

least half the existing indigenous languages are<br />

projected to disappear, erasing the ecological<br />

knowledge accumulated by countless generations.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> cultures face threats from many directions.<br />

Often they are direct targets of hatred <strong>and</strong><br />

Figure 2.1 Countries with Cultural <strong>and</strong> Biological Megadiversity<br />

Highest Cultural Diversity 1 Highest Biological Diversity 2<br />

Papua New<br />

Guinea<br />

Nigeria<br />

Cameroon<br />

Indonesia<br />

India<br />

Australia<br />

Mexico<br />

Zaire<br />

Brazil<br />

Colombia<br />

China<br />

Peru<br />

Malaysia<br />

Ecuador<br />

Madagascar<br />

1 Countries where more than 200 languages are spoken<br />

2 Countries listed by biologists as ‘megadiversity’ countries<br />

for their exceptional numbers of unique species<br />

Source: Worldwatch Institute, cited in Durning (1992:16)

10 <strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships<br />

hostility from the groups that dominate mainstream<br />

national societies. Other times they are<br />

victimized by policies <strong>and</strong> actions that are well<br />

intentioned but harmful. The imposition of alien<br />

l<strong>and</strong> tenure, religions, <strong>and</strong> educational systems<br />

may be motivated by the desire to “advance,”<br />

“integrate,” or help indigenous peoples “progress”<br />

in the modern world, yet these efforts often are<br />

self-defeating because they undermine the identity<br />

<strong>and</strong> values systems of the people being<br />

“helped.” Until recently the conventional wisdom<br />

of modernity held that the rural poor, including<br />

indigenous populations, were part of the problem<br />

of “underdevelopment,” sometimes even the main<br />

problem, rather than part of the solution. Blinded<br />

by cultural arrogance, too many conservation <strong>and</strong><br />

development projects have gone awry or done<br />

more harm than good because they did not tap the<br />

resourcefulness of local communities.<br />

The accelerating integration of the global<br />

economy now touches indigenous people living<br />

in the remotest corners of the planet.<br />

Technological change <strong>and</strong> consumerism introduced<br />

by the public <strong>and</strong> private sectors have<br />

undermined traditional value systems as the conversion<br />

from a subsistence economy to a cash<br />

economy follows in the wake of large-scale<br />

efforts to extract mineral, timber, <strong>and</strong> other natural<br />

resources. The result in many places has been<br />

a loss of social cohesion, displacement from<br />

traditional territories, dependency, impoverishment,<br />

<strong>and</strong> disease.<br />

List 2.1 Top 25 Countries by Number of Endemic Languages<br />

1. Papua New Guinea (847)<br />

2. Indonesia (655)<br />

3. Nigeria (376)<br />

4. India (309)<br />

5. Australia (261)<br />

6. Mexico (230)<br />

7. Cameroon (201)<br />

8. Brazil (185)<br />

9. Zaire (158)<br />

10. Philippines (153)<br />

11. USA (143)<br />

12. Vanuatu (105)<br />

13. Tanzania (101)<br />

14. Sudan (97)<br />

15. Malaysia (92)<br />

16. Ethiopia (90)<br />

17. China (77)<br />

18. Peru ( 75)<br />

19. Chad (74)<br />

20. Russia (71)<br />

21. Solomon Isl<strong>and</strong>s (69)<br />

22. Nepal (68)<br />

23. Colombia (55)<br />

24. Côte d’Ivoire (51)<br />

25. Canada (47)<br />

List 2.2 Megadiversity Countries: Concurrence with Endemic Languages<br />

(Countries in top 25 for endemic languages in bold)<br />

Countries listed alphabetically (rank in “Top 25,” list 2.1, in parentheses)<br />

Australia (5)<br />

Brazil (8)<br />

China (17)<br />

Colombia (23)<br />

Ecuador—<br />

India (4)<br />

Indonesia (2)<br />

Madagascar—<br />

Malaysia (15)<br />

Mexico (6)<br />

Peru (18)<br />

Zaire (9)<br />

Source: Maffi 1999.

<strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships 11<br />

Table 2.1<br />

Ethnolinguistic Groups (EG) in Global 200 Terrestrial Ecoregions (TER)<br />

Biogeographical<br />

Realm<br />

Number of<br />

terrestrial<br />

ecoregions<br />

(TERs) in realm<br />

Number <strong>and</strong><br />

percentage of<br />

TERs in realm<br />

that contain EGs<br />

Number of<br />

ethnolinguisitic<br />

groups (EGs)<br />

in realm<br />

Number <strong>and</strong><br />

percentage of<br />

the realm s EGs<br />

living in the<br />

realm s TERs<br />

Afrotropical<br />

Neotropical<br />

Nearctic<br />

Indomalayan<br />

Oceanian<br />

Palearctic<br />

Australasian<br />

WORLD<br />

32<br />

30<br />

11<br />

24<br />

3<br />

21<br />

15<br />

136<br />

30 (94%) 1,934 1,364 (71%)<br />

132 (97%) 2 6,867 3 4,889 (71%)<br />

28 (93%)<br />

830<br />

535 (64%)<br />

11 (100%)<br />

24 (100%)<br />

223<br />

1,547<br />

80 (36%)<br />

1,117 (72%)<br />

3 (100%)<br />

153<br />

9 (6%)<br />

21 (100%)<br />

15 (100%)<br />

748<br />

1,432<br />

662 (89%)<br />

1,122 (78%)<br />

Source: WWF-International, People <strong>and</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> Program, Gl<strong>and</strong>, Switzerl<strong>and</strong>, 1998.<br />

1.4 <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>and</strong> International<br />

Environmental Policy<br />

WWF’s indigenous peoples policy recognizes that<br />

“unfortunately, [indigenous] cultures have become<br />

highly vulnerable to destructive forces related to<br />

unsustainable use of resources, population expansion,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the global economy,” <strong>and</strong> that “industrialized<br />

societies bear a heavy responsibility for the<br />

creation of these destructive forces.” It points to<br />

the need to “correct the national <strong>and</strong> international<br />

political, economic, social, <strong>and</strong> legal imbalances<br />

giving rise to these destructive forces, <strong>and</strong> to<br />

address their local effects.”<br />

WWF is not alone in this recognition. The 1992<br />

United Nations Conference on Environment <strong>and</strong><br />

Development in Rio de Janeiro recognized<br />

indigenous peoples as important stakeholders in<br />

environment <strong>and</strong> development policies at the<br />

international level. Almost every relevant international<br />

instrument on the environment signed at<br />

or developed after the Rio Summit includes provisions<br />

related to indigenous peoples or has initiated<br />

processes to promote their participation.<br />

Agenda 21, the international agreement on follow-up<br />

actions to the conference, considers<br />

indigenous peoples to be a “Major Group” in<br />

trailblazing a path toward sustainable development,<br />

<strong>and</strong> proposes a number of objectives <strong>and</strong><br />

activities that are compatible with WWF’s<br />

agenda (see box 2.1). The international policy<br />

forums that address conservation issues—the<br />

Commission on Sustainable Development, the<br />

Convention on Biological Diversity, the<br />

Convention to Combat Desertification, the Inter-<br />

Governmental Forum on Forests, <strong>and</strong> the Ramsar<br />

Convention, among others—include indigenous<br />

peoples as essential stakeholders. In policy<br />

debates, the interests of indigenous peoples often<br />

coincide with those of WWF <strong>and</strong> other conservation<br />

organizations, especially when dealing with<br />

environmental threats <strong>and</strong> the underlying causes<br />

of biodiversity loss.<br />

Apart from the arena of international environmental<br />

policy, an array of multinational organizations<br />

has incorporated policy provisions on<br />

indigenous peoples into their program operations.

12 <strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships<br />

Particularly prominent are the World Bank,<br />

whose Operational Directive on <strong>Indigenous</strong><br />

<strong>Peoples</strong> is well known <strong>and</strong> frequently cited, <strong>and</strong><br />

the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) <strong>and</strong><br />

the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which have<br />

similar policies.<br />

Many governments of developed countries have<br />

also adopted policies to ensure that their international<br />

assistance programs for development <strong>and</strong><br />

the environment respect indigenous rights.<br />

Among others, Denmark, the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, Spain,<br />

<strong>and</strong> more recently the European Union have all<br />

specifically addressed the issue of local community<br />

rights <strong>and</strong> interests in undertaking development<br />

<strong>and</strong> environmental actions with indigenous<br />

groups. This convergence in policy is an important<br />

str<strong>and</strong> in the growing partnership between<br />

WWF <strong>and</strong> the aid agencies of these governments<br />

on conservation projects worldwide.<br />

Finally, a broad spectrum of international conservation<br />

organizations has adopted policies geared<br />

toward indigenous peoples. WWF adopted its<br />

Statement of Principles on <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> (see Annex) in May 1996. In<br />

October 1996, the World <strong>Conservation</strong> Congress<br />

of the World <strong>Conservation</strong> Union (IUCN) passed<br />

a set of eight resolutions related to indigenous<br />

peoples. IUCN recognized them as repositories<br />

of traditional knowledge about biodiversity, <strong>and</strong><br />

noted the role they play in protected areas,<br />

forests, marine <strong>and</strong> coastal habitats, <strong>and</strong> a host of<br />

other environmental areas. Nongovernmental<br />

organizations (NGOs) dealing with forest issues,<br />

such as the World Rainforest Movement <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Rainforest Foundation, have made issues affecting<br />

indigenous peoples a fundamental component<br />

of their strategy. Although some environmental<br />

groups like The Nature Conservancy, Friends of<br />

the Earth, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> International do not<br />

have specific policies or programs dealing with<br />

indigenous peoples, they have carried out activities<br />

in coordination with indigenous organizations<br />

on many occasions <strong>and</strong> have expressed<br />

interest in indigenous issues.<br />

Perhaps the most notable exception to this policy<br />

convergence in the international conservation<br />

movement is Greenpeace, which, in spite of<br />

internal discussions <strong>and</strong> pressure, has declared<br />

indigenous peoples outside its orbit of priorities.<br />

II. WWF’s Approach to Working<br />

with <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><br />

WWF seeks to partner with indigenous groups<br />

when conservation of their l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> resources<br />

coincides with its conservation priorities.<br />

WWF’s partnerships with indigenous peoples are<br />

based on recognition of their legitimate rights<br />

<strong>and</strong> interests. These two affirmations are the cornerstones<br />

of WWF’s indigenous peoples policy,<br />

which includes a set of principles to guide the<br />

formation of partnerships. This section discusses<br />

the principles, <strong>and</strong> the next section addresses the<br />

programmatic guides to partnership.<br />

2.1 Achieving WWF’s <strong>Conservation</strong> Mission<br />

WWF’s guiding philosophy is that the Earth’s<br />

natural systems, resources, <strong>and</strong> life forms<br />

should be conserved for their intrinsic value <strong>and</strong><br />

for the benefit of future generations. WWF’s<br />

commitment to collaborating with indigenous<br />

peoples to achieve conservation is firm, but not<br />

unconditional. As stated in WWF’s indigenous<br />

peoples policy:<br />

WWF may choose not to support, <strong>and</strong><br />

may actively oppose, activities it judges<br />

unsustainable from the st<strong>and</strong>point of<br />

species or ecosystems… even if such<br />

activities are carried out by indigenous<br />

peoples. WWF seeks out partnerships<br />

with local communities, grassroots<br />

groups, nongovernmental organizations,<br />

<strong>and</strong> other groups, including indigenous<br />

communities <strong>and</strong> indigenous peoples’<br />

organizations, that share WWF’s commitment<br />

to the conservation of biodiversity,<br />

sustainable use of resources, <strong>and</strong> pollution<br />

prevention.<br />

This echoes Article 10(c) of the Convention on<br />

Biological Diversity, which requires parties to<br />

“protect <strong>and</strong> encourage customary use of biological<br />

resources in accordance with traditional cultural<br />

practices that are compatible with<br />

conservation or sustainable use requirements.”<br />

This means that traditional systems for environmental<br />

management <strong>and</strong> for the use of biological<br />

resources should be supported by conservation<br />

organizations as long as those systems contribute<br />

to the conservation <strong>and</strong> sustainable use of biodiversity.<br />

Clearly those systems are more likely to<br />

remain sustainable as circumstances change if

<strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships 13<br />

Box 1 AGENDA 21 - CHAPTER 26: Recognizing <strong>and</strong> Strengthening the Role of<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> People <strong>and</strong> Their Communities<br />

Objectives<br />

26.3 In full partnership with indigenous people <strong>and</strong> their communities, Governments <strong>and</strong>, where<br />

appropriate, intergovernmental organizations should aim at fulfilling the following objectives:<br />

(a) Establishment of a process to empower indigenous people <strong>and</strong> their communities through<br />

measures that include:<br />

(i) Adoption or strengthening of appropriate policies <strong>and</strong>/or legal instruments at<br />

the national level;<br />

(ii) Recognition that the l<strong>and</strong>s of indigenous people <strong>and</strong> their communities should<br />

be protected from activities that are environmentally unsound or that the indigenous<br />

people concerned consider to be socially <strong>and</strong> culturally inappropriate;<br />

(iii) Recognition of their values, traditional knowledge <strong>and</strong> resource management<br />

practices with a view to promoting environmentally sound <strong>and</strong> sustainable<br />

development;<br />

(iv) Recognition that traditional <strong>and</strong> direct dependence on renewable resources <strong>and</strong><br />

ecosystems, including sustainable harvesting, continues to be essential to the<br />

cultural, economic <strong>and</strong> physical well-being of indigenous people <strong>and</strong> their<br />

communities;<br />

(v) Development <strong>and</strong> strengthening of national dispute-resolution arrangements in<br />

relation to settlement of l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> resource-management concerns;<br />

(vi) Support for alternative environmentally sound means of production to ensure a<br />

range of choices on how to improve their quality of life so that they effectively<br />

participate in sustainable development;<br />

(vii) Enhancement of capacity-building for indigenous communities, based on the<br />

adaptation <strong>and</strong> exchange of traditional experience, knowledge <strong>and</strong> resourcemanagement<br />

practices, to ensure their sustainable development;<br />

(b) Establishment, where appropriate, of arrangements to strengthen the active participation of<br />

indigenous people <strong>and</strong> their communities in the national formulation of policies, laws <strong>and</strong> programmes<br />

relating to resource management <strong>and</strong> other development processes that may affect<br />

them, <strong>and</strong> their initiation of proposals for such policies <strong>and</strong> programmes;<br />

(c) Involvement of indigenous people <strong>and</strong> their communities at the national <strong>and</strong> local levels in<br />

resource management <strong>and</strong> conservation strategies <strong>and</strong> other relevant programmes established to<br />

support <strong>and</strong> review sustainable development strategies, such as those suggested in other programme<br />

areas of Agenda 21.<br />

Source: UNCED 1992.

14 <strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships<br />

indigenous peoples <strong>and</strong> local communities participate<br />

in determining the criteria for measuring sustainability.<br />

If they underst<strong>and</strong> the reasons for<br />

changing behaviors, they are more likely to make<br />

the changes.<br />

There is no blueprint for working with indigenous<br />

peoples. Each situation is different, not<br />

only culturally but socially, politically, economically,<br />

<strong>and</strong> geographically. While WWF’s<br />

involvement is based on a clear set of principles,<br />

a solid underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the links between biological<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultural diversity, <strong>and</strong> a genuine<br />

appreciation for indigenous peoples’ contribution<br />

to biodiversity conservation, its operational<br />

approach should be sensitive <strong>and</strong> flexible in order<br />

to maximize the input of its partners.<br />

2.2 Why Human Rights <strong>and</strong><br />

Self-Determination Should Matter<br />

to <strong>Conservation</strong>ists<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> organizations repeatedly <strong>and</strong> forcefully<br />

insist that development <strong>and</strong> the environment<br />

must be approached from a human-rights perspective.<br />

The conservation movement has often<br />

responded that human rights are beyond its mission<br />

<strong>and</strong> m<strong>and</strong>ate. Increasingly the difference<br />

between these two viewpoints is narrowing.<br />

Environmental human rights—the right of present<br />

<strong>and</strong> future generations to enjoy a healthy life in a<br />

healthy environment—are implicitly at the heart of<br />

the environmental agenda, <strong>and</strong> will become more<br />

explicitly so in the future. Environmental human<br />

rights are linked to the right to a decent quality of<br />

life <strong>and</strong> to other related rights recognized in the<br />

International Covenant on Economic, Social, <strong>and</strong><br />

Cultural Rights. WWF <strong>and</strong> other conservation<br />

organizations recognize that indigenous groups<br />

cannot be expected to commit themselves to conservation<br />

if their livelihoods are in peril from lack<br />

of secure tenure to l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> resources. Indeed, it is<br />

the strength of their claim to the l<strong>and</strong>, coupled with<br />

long histories of managing it wisely, that make<br />

them attractive potential partners for environmental<br />

stewardship. They cannot play this role under conditions<br />

of political oppression <strong>and</strong> marginalization.<br />

The more people’s basic needs are met <strong>and</strong> their<br />

rights respected, the more they will be willing <strong>and</strong><br />

able to engage in biodiversity conservation because<br />

they underst<strong>and</strong> it is in their own interest to do so.<br />

For indigenous peoples, the question of human<br />

rights is bound up with the struggle for selfdetermination,<br />

which involves control of traditional<br />

resources <strong>and</strong> cultural autonomy within<br />

existing nation states. WWF acknowledges<br />

indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination,<br />

<strong>and</strong> has built its own policies on it. When<br />

indigenous peoples define themselves as distinct<br />

nations <strong>and</strong> seek political autonomy, WWF<br />

respects their efforts to negotiate their status with<br />

governments, but does not consider this to be an<br />

issue on which it must take sides.<br />

III. Key Program Issues for<br />

<strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Organizations</strong><br />

Collaboration with indigenous peoples falls<br />

under several programmatic areas. This section<br />

explores six of them: 1) participation <strong>and</strong> prior<br />

informed consent; 2) protected areas; 3) traditional<br />

ecological knowledge <strong>and</strong> management<br />

practices; 4) alternative economic options <strong>and</strong><br />

benefit sharing; 5) mitigation of environmental<br />

impacts; <strong>and</strong> 6) conservation capacity-building.<br />

Many of these issues are discussed in more detail<br />

in the case studies that follow.<br />

3.1 Prior Informed Consent<br />

Prior informed consent (PIC) is a fundamental<br />

principle for indigenous collaboration with outside<br />

organizations <strong>and</strong> the basis for protecting all<br />

other rights. PIC requires outsiders proposing<br />

any action to fully inform indigenous groups of<br />

the reasons for the activity, how it will be implemented<br />

in detail, the potential risks involved, <strong>and</strong><br />

how this activity realistically can be expected to<br />

affect other aspects of community life in the short<br />

<strong>and</strong> long terms. If the indigenous community<br />

withholds its consent, no activities can begin, <strong>and</strong><br />

activities already under way must be halted. The<br />

following types of activities relevant to biodiversity<br />

conservation should be subject to PIC:<br />

• the extraction of renewable or nonrenewable<br />

resources from indigenous communities<br />

or their territories;<br />

• the acquisition of knowledge from a person<br />

or people, whether for commercial or noncommercial<br />

purposes; <strong>and</strong><br />

• all projects affecting indigenous communities,<br />

including infrastructure construction of<br />

roads <strong>and</strong> dams, <strong>and</strong> colonization schemes.

<strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships 15<br />

Since legal frameworks <strong>and</strong> tools to exercise <strong>and</strong><br />

protect PIC are still in their infancy, WWF<br />

addresses this issue primarily at the local level<br />

through agreements with communities. This<br />

does not foreclose efforts to establish needed<br />

legal tools at national <strong>and</strong> other levels.<br />

3.2 Protected Areas<br />

The establishment of protected areas is a primary<br />

tool for conserving biodiversity around the<br />

world. <strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples inhabit nearly 20 percent<br />

of the world’s surface, or close to three<br />

times the total surface covered by protected<br />

areas. Of course, many of the world’s protected<br />

areas overlap with indigenous l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> territories.<br />

For example, in Latin America local populations,<br />

most of them indigenous, inhabit 86<br />

percent of protected areas (Amend 1992).<br />

The protected area model is presumed to be a<br />

creation of modern Western societies, dating<br />

back to the establishment of Yellowstone<br />

National Park in the United States in 1872. Yet<br />

there are similar models that are much older. For<br />

hundreds if not thous<strong>and</strong>s of years, traditional<br />

societies have established “sacred” areas within<br />

the compass of their territorial l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> waters<br />

where human activities have been very limited<br />

<strong>and</strong> strictly regulated. This traditional concept of<br />

protected areas is alive <strong>and</strong> functioning in many<br />

parts of the world, although it generally lacks<br />

recognition <strong>and</strong> support from modern states <strong>and</strong><br />

societies. Sadly, despite their respect for nature,<br />

indigenous communities have been expelled from<br />

their traditional l<strong>and</strong>s to create reserves <strong>and</strong><br />

parks. The livelihoods <strong>and</strong> cultures of these<br />

communities have been severely disrupted, turning<br />

protected areas into an enemy rather than a<br />

guarantor of community survival.<br />

WWF has joined with the World Commission on<br />

Protected Areas (WCPA) to develop a new<br />

framework policy on indigenous/traditional peoples<br />

<strong>and</strong> protected areas. This policy promotes<br />

the concept of partnerships between indigenous<br />

communities <strong>and</strong> the public or private institutions<br />

responsible for administering a park or reserve<br />

when the local groups’ l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> resources fall<br />

within the boundaries of the protected area. The<br />

policy also supports indigenous peoples’ own<br />

actions to protect their territories. Within this<br />

framework, conservation groups are encouraged<br />

to support the growing number of comanagement<br />

arrangements between the state <strong>and</strong> indigenous<br />

peoples, <strong>and</strong> to work to extend recognition of<br />

indigenous protected areas as self-regulated parts<br />

of national protected-area systems.<br />

3.3 Traditional Ecological Knowledge<br />

Traditional knowledge is an important resource<br />

for development of strategies to conserve biodiversity.<br />

Generations of interaction with specific<br />

habitats <strong>and</strong> species can provide a long-term perspective<br />

on ecosystem dynamics. Anthropologists<br />

<strong>and</strong> other researchers have frequently documented<br />

how various traditional peoples have developed<br />

sophisticated classification systems, in many<br />

cases producing more complete taxonomies than<br />

those of Western science. Traditional knowledge<br />

is also a catalyst for cultural adaptation to environmental<br />

conditions. One of the great ironies<br />

facing many indigenous peoples is that scientific<br />

<strong>and</strong> commercial interest in their ecological knowledge<br />

<strong>and</strong> resource management practices is<br />

increasing while traditional knowledge systems<br />

are disappearing at an accelerating rate as globalization<br />

makes the world more biologically <strong>and</strong><br />

culturally uniform.<br />

WWF has worked with indigenous peoples in<br />

several countries to protect <strong>and</strong> revitalize traditional<br />

knowledge. In Thail<strong>and</strong>, WWF supports<br />

the Karen people’s efforts to maintain <strong>and</strong> consolidate<br />

their cultural practices, <strong>and</strong> pays particular<br />

attention to strengthening knowledge of local<br />

ecosystems. The People <strong>and</strong> Plants Program<br />

implements various ethnobotany projects in Asia,<br />

Africa, <strong>and</strong> the Pacific to recuperate, protect, <strong>and</strong><br />

revitalize traditional botanical knowledge, <strong>and</strong> to<br />

help local people conserve their plant resources.<br />

Traditional management practices also have much<br />

to offer to biodiversity conservation. Article 10(c)<br />

of the Convention on Biological Diversity<br />

requires recovery <strong>and</strong> support of these practices<br />

when they are “compatible with conservation or<br />

sustainable use requirements.” The assumption<br />

underlying this injunction is that these practices<br />

not only have specific local values but can be<br />

integrated into national efforts to enhance biodiversity<br />

conservation in a given country.<br />

Some of WWF’s work with indigenous groups<br />

supports that assumption. For instance, a study<br />

with indigenous communities in the Arctic<br />

showed that their use of wildlife was essentially

16 <strong>Conservation</strong> Partnerships<br />

compatible with conservation objectives, <strong>and</strong> that<br />

external market forces have caused recent disruptions.<br />

Based on this analysis, <strong>and</strong> on working<br />

with local people, WWF developed guidelines<br />

for the sustainable use of wildlife in the region.<br />

Many of the concepts in the guidelines are applicable<br />

to other areas where communities are concerned<br />

that their wildlife is dwindling.<br />

Fortunately international environmental law<br />

increasingly recognizes, through agreements such<br />

as the Convention on Biological Diversity, that<br />

the knowledge, innovations, <strong>and</strong> practices of<br />

indigenous peoples <strong>and</strong> local communities are<br />

vital resources for preserving the genetic heritage<br />

of the planet. Systematic effort is needed to help<br />

revitalize <strong>and</strong> protect such knowledge in collaboration<br />

with concerned communities, with full<br />

respect for their intellectual property rights.<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples should have the opportunity<br />

to benefit fairly from the use <strong>and</strong> application of<br />

their knowledge, <strong>and</strong> this will serve our common<br />

interest by strengthening their ability <strong>and</strong> commitment<br />

to act as environmental stewards.<br />

3.4 Benefit Sharing <strong>and</strong> Economic<br />

Alternatives<br />

Long-term conservation of indigenous peoples’<br />

territories <strong>and</strong> resources requires that communities<br />

directly <strong>and</strong> equitably benefit from the use of<br />

their l<strong>and</strong>. In most cases, conservation implies<br />

trade-offs that have direct or indirect impact on<br />

local livelihoods. <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong> traditional people<br />

should not be expected to participate in conservation<br />

activities that do not contribute to<br />

improving their quality of life. Ensuring an<br />

improved quality of life often involves the creation<br />

of economic alternatives that promote sustainable<br />

resource use <strong>and</strong> generate income to<br />

counterbalance market pressures to overexploit<br />

resources for short-term gain. Care must also be<br />

taken that benefits are broadly distributed to<br />

avoid fragmenting the community <strong>and</strong> undermining<br />

its ability to manage its resource base wisely.<br />

3.5 Mitigation of Environmental Impacts<br />

<strong>Indigenous</strong> groups <strong>and</strong> conservation organizations<br />

are both concerned about the destructive<br />

impact that ill-conceived logging, mining, oil<br />

exploitation, <strong>and</strong> other development efforts can<br />

have on the environment. These issues have converted<br />

many indigenous groups into activists<br />

fighting to defend the integrity of their l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

ecosystems. Through coordinated <strong>and</strong> mutually<br />

supportive work, conservationists <strong>and</strong> indigenous<br />

peoples can mitigate these threats <strong>and</strong> promote<br />

practices that lead to sustainable development.<br />

Article 7 of ILO Convention 169 requires governments<br />

to carry out environmental impact assessments<br />

(EIAs) for any activities taking place on the<br />

l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> territories of indigenous peoples that<br />

could affect the quality of their environment <strong>and</strong><br />

resource bases. To help ensure that this proscription<br />

is followed, WWF has pledged to help monitor<br />

development of EIAs for external interventions<br />

in any indigenous territory where WWF works so<br />

that affected communities are fully informed,<br />

allowed to voice their concerns, <strong>and</strong> able to defend<br />

their rights. WWF, in cooperation with concerned<br />

indigenous organizations, will also urge governments<br />

to put in place all necessary measures to<br />