Ondatra zibethicus - NOBANIS

Ondatra zibethicus - NOBANIS

Ondatra zibethicus - NOBANIS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>NOBANIS</strong> –Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet<br />

<strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong><br />

Author of this fact sheet:<br />

Christina Birnbaum, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences,<br />

Kreutzwaldi 64, 51014 Tartu, chbirnbaum@yahoo.com<br />

Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet:<br />

Birnbaum, C. (2006): <strong>NOBANIS</strong> – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>. – From: Online Database<br />

of the North European and Baltic Network on Invasive Alien Species – <strong>NOBANIS</strong> www.nobanis.org, Date of access<br />

x/x/200x.<br />

Species description<br />

Scientific names: <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>, (L., 1766) Cricetidae (Muridae, Arvicolinae)<br />

Synonyms: <strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica, Castor <strong>zibethicus</strong>, Fiber <strong>zibethicus</strong>, Myocastor <strong>zibethicus</strong>, Mus<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong>, Mussascus<br />

Common names: Muskrat (Musquash) (GB), Swamp rabbit (GB), Marsh rabbit (GB), Marsh hare<br />

(GB), Bisam (DE), Bisamratte (DE), Moschusratte (DE), Zwergbiber (DE), Zibethratte (DE),<br />

Bisambiber (DE), Biberratte (DE), Sumpfkaninchen (DE), Sumpfhase (DE), Muschmaus (DE),<br />

Zibetmaus (DE), Wasserratte (DE), Bisamrotte (DK), <strong>Ondatra</strong> (EE), Piisamrott (EE), Piisami (FI),<br />

Moskusrotta (IS), <strong>Ondatra</strong> (LT), <strong>Ondatra</strong> / bizamžurka (LV), Piżmak (PL), Ондáтра (RU).<br />

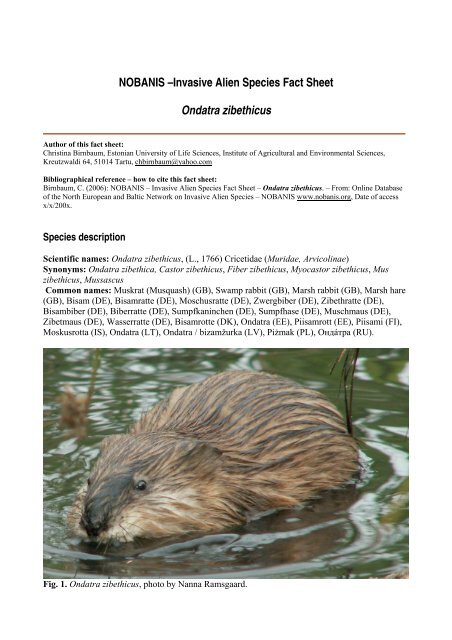

Fig. 1. <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>, photo by Nanna Ramsgaard.

Fig. 2 and 3. Close-up of tail and hind feet of <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>, photo by Nanna Ramsgaard<br />

Species identification<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> can attain a head and body length of 40 cm, a tail length of up to 25 cm, and a<br />

maximum weight of 1.5 or 2 kg. The species is especially adapted to an aquatic mode of life: its tail<br />

is naked and laterally flattened, the nose and ears are closeable, and the edges of its hind feet carry<br />

swimming bristles (Burghause 1988). It has a “rat-like” appearance but is actually closely related to<br />

voles Microtus spp. and lemmings Lemmus spp (Banfield 1974).<br />

Native range<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> originates from North America.<br />

Alien distribution<br />

The central European populations of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> are recruited from at least two centers of<br />

dispersal. Two males and three females were released for hunting purposes at Dobrisch near Prague<br />

around 1905 (cf. Hoffman 1958). In 1908 it was introduced to the Czech Republic for fur farming.<br />

Some animals were said to have been kept at Krumau on the upper Moldavia River at about the<br />

same time (possibly since 1888), and another group of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> was supposedly released at<br />

Tabor in 1905 (according to Hoffman 1958). Within a few years, these private stocks probably gave<br />

rise to a wild population in Bohemia, which gradually extended its range, invading Bavaria in 1914,<br />

and Saxony and Silesia in 1917. From their Bohemian center, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> spread across the<br />

Sudeten Mountains into the Oder Basin, across the Lausitz Mountains to the Spree River, over the<br />

Fichtelgebirge to the rivers Saale and Main, and over the Bohemian Forest to the Naab and Danube.<br />

They spread rapidly along the Elbe River, attaining its mouth in 1947 (the first specimens were<br />

2

found in Hamburg in 1933; i.e. after having covered a straight distance of 550 km in only 28 years;<br />

their colonization of the Elbe and Havel rivers is described by Hoffmann 1958). O. <strong>zibethicus</strong><br />

subsequently colonized eastern Germany, spreading westward across the Mecklenburg lake district<br />

(Kintzel 1985; cf. Kirchner 1954). In western Germany, Schröpfer & Engstfeld (1983) state that<br />

they have inhabited the entire Emsland, for instance, since 1967.<br />

In southwestern Germany, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> invaded the counties of Kehl, Offenburg and Lahr in 1932,<br />

and the counties of Lörrach, Freiburg, Emmendingen, Müllheim, and Säckingen in 1955. By 1980,<br />

it had colonized every county in the State of Baden-Württemberg. O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is now naturalized<br />

throughout all of Germany (Heidecke & Seide 1986).<br />

For financial reasons, Finland imported about 1, 100 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> from Germany, Czechoslovakia<br />

and North America (Artimo 1960). The animals were released in a total of 293 localities all over<br />

Finland from 1919 and onwards. Within 35 years (1920-1955) O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> had established in<br />

almost all available habitats, with the exception of those in the northernmost parts of Finland. In<br />

northern Finland, the spread has been distinctly slower than in southern Finland. The spread has<br />

varied within limits of 4-120 km per year, but usually O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> has spread at rate of 10-20 km<br />

per year.<br />

From northern Finland O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> spread into Sweden, and in 1957 the species had fully<br />

occupied the lower region of the border river Torneälven (Artimo 1960). In Sweden, there have<br />

been and still are excellent possibilities of studying the dispersal rate of the O. <strong>zibethicus</strong><br />

southwards in the country (Danell 1996).<br />

In 1927, 10 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> were introduced from Finland to Russia. Twenty individuals from Finland<br />

were released to the wild (nature) near the islands of Solovets. Beginning in 1928, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> was<br />

released in massive numbers in the territory of the Soviet Union. By 1955 large areas near different<br />

water bodies were occupied by about 160,000 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> (Lavrov 1957).<br />

In the early 1930s O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> was also introduced to the Kola Peninsula (Lund and Wikan 1995).<br />

In total, about 1,000 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> were released on the Kola Peninsula during 1931-1936. Just<br />

before 1950 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> occurred all over the peninsula (Semjonov-Tian-Sjanskij 1987).<br />

1650 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> were imported into Russia in 1928 - 1932 from Finland, Canada and England.<br />

After that ten thousand animals caught in new settlements, were released in the nature. Natural<br />

moving happened very quickly too and by 1970 the muskrat has occupied almost all suitable<br />

territories. Their distribution in Russia is from the western border up to Kamchatka. It exceeds the<br />

natural area significantly.<br />

Between 1980 and 1988 there are very few observations of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Norway. Since 1988<br />

there has been a rapid population increase in Sör-Varanger, and today O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> has spread to<br />

almost every part of the municipality (Danell 1996). Little is known about the distribution and<br />

abundance of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in other parts of Finnmark or the rest of Norway, but it seems likely that<br />

the species has a scattered distribution and low population numbers (Lund 1995). O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> has,<br />

however, been documented shot or caught in gillnets intended for fishing, in Hattfjelldal in<br />

Nordland county and in Lierne in North Trøndelag county in 2005. For both areas it appears that O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong> has migrated into Norway along watersheds crossing the mountain range along the<br />

border. South of the mountainous areas the O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> probably will spread easier across the<br />

border and also spread north-south on rivers in southern Norway.<br />

3

The incidental record of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Denmark was from the island of Rømø in 1989<br />

(Ramsgaard and Christensen 2006). Since 2000, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> has been regularly reported from the<br />

southern parts of Denmark close to the German borders, the size of the population has, however, not<br />

been determined yet (Ramsgaard 2005, Ramsgaard and Christensen 2006).<br />

In France, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> farms were founded in the southern Vosges Mountains after World War I.<br />

When the price of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> furs plunged during the 1920s, a number of farms closed and<br />

released their animals (e.g. 500 animals in 1928 near Belfort). This population spread to<br />

Switzerland and Alsace by 1930, and the Meuse and Moselle rivers in 1935.<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> was introduced twice to Estonia: in 1947, 190 animals and in 1952, 361 animals,<br />

raised from the original stock, were released to water bodies in southern and western parts of<br />

Estonia (N. Laanetu, pers.comm.).<br />

The first record of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Latvia is from 1961; it spread from Belarus and later also from<br />

Estonia and Lithuania, where it was introduced (Ozols 1997).<br />

Pathways of introduction<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> was introduced for fur farming and breeding purposes.<br />

Alien status in region<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is present in most of the countries of the region (see table 1). In some parts of Estonia<br />

the American mink (Mustela vison) has displaced O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> by taking its habitat (Kukk 2001).<br />

However, in other parts of Estonia O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is still present, e.g. in South-Estonia and near the<br />

Narva reservoir (in north-east of Estonia) (Kull et al. 2005).<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> occurs throughout Poland. However, within the last 15 years, the numbers have<br />

dropped significantly (by 81% in NW Poland). This is partly due to the presence of Mustela vison,<br />

since Mustela vison occurs only in the northern part of the country and the decrease in O. <strong>zibethicus</strong><br />

was recorded in all of Poland (Polish Alien Species Database).<br />

In Norway O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> occur in areas with quite unfavourable habitats where population density is<br />

very low (Danell 1996).<br />

The status of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Latvia is not known; but in later years the number of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> has<br />

decreased, because of its natural enemies, such as Mustela vison and Arvicola terrestris (Ozols<br />

1997, J. Ozoliņš, pers. comm.).<br />

In Russia O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> kept its new huge area, but its quantity has significantly decreased for the<br />

last 15 - 20 years. There are many reasons for the quantity decline, but in the north of the area there<br />

has been a reduction of edible plants and intensive growth of inedible plants (Павлов, и др.1973,<br />

Соколов, Лавров, 1993.)<br />

4

Country Not Not Rare Local Common Very Not<br />

found established<br />

common known<br />

Denmark X<br />

Estonia X<br />

European part of Russia X<br />

Finland X<br />

Faroe Islands X<br />

Germany X<br />

Greenland X<br />

Iceland X<br />

Latvia X<br />

Lithuania X<br />

Norway X<br />

Poland X<br />

Sweden X<br />

Table 1. The frequency and establishment of <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>, please refer also to the<br />

information provided for this species at www.nobanis.org/search.asp. Legend for this table: Not<br />

found –The species is not found in the country; Not established - The species has not formed selfreproducing<br />

populations (but is found as a casual or incidental species); Rare - Few sites where it is<br />

found in the country; Local - Locally abundant, many individuals in some areas of the country;<br />

Common - Many sites in the country; Very common - Many sites and many individuals; Not<br />

known – No information was available.<br />

Ecology<br />

Habitat description<br />

The animals live semi-aquatically. They are crepuscular, spending the day in burrows or floating<br />

reed lodges up to 1.5 m in height (mostly during winter – depending on habitat and climate)<br />

(Heidecke & Seide 1986, Ramsgaard 2005).<br />

Reproduction and life cycle<br />

Females usually throw 3 or 4 times per year from late April on, producing 2 to 12 offspring (4 to 7<br />

on average) annually. In colder climates females may throw only twice a year (Ramsgaard 2005).<br />

The young grow a nest coat after 18 days, an adolescent coat after about 4 weeks, and the adult coat<br />

at about 4 months (Burghause 1988). The rate of reproduction depends on food supply, population<br />

density, and water temperature. The mortality of the offspring increases at low water temperatures<br />

and high population densities (cf. Meinert & Diemer 1977). Females may attain sexual maturity at<br />

the age of five months, and the males after seven months (Heidecke & Seide 1986).<br />

Dispersal and spread<br />

The principal migration period of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is during spring (peaking in March) and fall<br />

(peaking in October). The migration period may extend from fall to spring during very mild<br />

winters. The rate of dispersal varies from year to year, depending mostly on the survival rate of the<br />

litter in spring, as well as on the amount of precipitation during the summer, as low water levels<br />

strongly impede the dispersal of the species (Burghause 1996). Dispersal rates of 6-8 km/year have<br />

been reported from several countries in Europe including Denmark (Ramsgaard and Christensen<br />

2006 and references therein). High water levels may provide stochastic dispersal opportunities<br />

(Ramsgaard 2005). For example O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> can migrate long distances (up to 160 km/day) by<br />

rafting, being carried long distances by river currents (Böhmer et al 2001)<br />

5

Impact<br />

Affected habitats and indigenous organisms<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> feeds mainly on the plants of reed belt communities (Pietsch 1982; Krauss 1990;<br />

Diemer 1996), particularly on common reed (Phragmites communis). According to Burghause<br />

(1988), one animal is capable of cropping 1.5 m 2 per night. O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> also likes to dig for roots,<br />

and it is particularly attracted to the tubers of Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus), a<br />

common neophyte in river plains (Burghause 1988, 1996). O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is a generalist but usually<br />

only eats a few species, which for example could be the plant species mentioned above (Ramsgaard<br />

2005). Small well-vegetated lakes with relatively stable water levels are especially favored by O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong> in Finnish waters, but heavy impacts have also been reported in waters with poor stands<br />

of helophytes (Rintanen 1976). O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> grazing affects the structure of littoral vegetation<br />

(Danell 1977, 1979). This change in vegetation affects communities of aquatic invertebrates<br />

(Nummi et al. 2005).<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> may sometime feed on crayfish, zebra mussels, crustaceans, and insects (cf. Ulbrich<br />

1928, Hoffmann 1958), bivalves - including threatened taxa such as Anodonta, Unio, and the<br />

freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera (cf. Brander 1955; Baumann & Everding 1986;<br />

Hochwald 1990; Zimmermann et al. 2000). This indirectly affects rare fish species that deposit their<br />

eggs in bivalves, such as the bitterling (Rhodeus amarus).<br />

The effects of spreading of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> are often linked with those of anthropogenic pollution, as<br />

in the case of the decline of reed belts in many lakes (Kintzel 1985; Barthelmes 1991). According to<br />

Barthelmes (1991), long-term observations at a lake in Berlin (Grosser Müggelsee) have shown that<br />

the decline in reed cover may have been due mainly to the feeding pressure exerted by O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong>. In Kintzel (1985), Stüber reports that at the Lake of Döbbertin "the plant cover was<br />

usually destroyed completely after one or two years, after which O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> moved on".<br />

Bernhardt and Schröpfer (1992) have shown that in the Ems region O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> removes bulrushes<br />

(Typha latifolia), promoting the development of club-rushes (Schoenoplectus lacustris).<br />

All in all, the general opinion on the impact of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> on their habitat is mixed, especially in<br />

northern Europe. On one hand, the animal is regarded as a positive factor because it creates<br />

openings in dense vegetation stands and it prevents lakes from being overgrown by vegetation. On<br />

the other, it has been blamed for destroying valuable vegetation and creating mud-flats. Depending<br />

on human interest in the development of the particular wetland, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> may be regarded as a<br />

valuable element or as a “pest” species (Danell 1996).<br />

The American mink (Mustela vison), which is now spreading throughout Germany, is an important<br />

predator of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> (Burghause 1988; Stubbe 1993). Other natural enemies are martens,<br />

European polecats, weasels, foxes, lynxes and various birds of prey and large owls; however, the<br />

populations of these predators have been anthropogenically decimated, so that their predation<br />

pressure on O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is low. (O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is difficult to catch for most of the predators since it<br />

spends most of its time in the water. The O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> taken by the mentioned predators are often<br />

sick or young animals which spend more time on land (Ramsgaard 2005).<br />

Genetic effects<br />

No known genetic effects.<br />

Human health effects<br />

According to Hoffmann (1958), O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is host to a great number of parasites (41 species of<br />

6

trematodes, 22 species of cestodes, 27 species of nematodes, and others), notably various species<br />

capable of infesting humans, such as the dog tapeworm (Taenia hydatigena), the cat tapeworm<br />

(Taenia taeniaformis), and the dwarf tapeworm (Echinococcus multilocuralis; cf. Diemer 1996).<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> only occasionally affect humans directly. This occurs in situations when the animals<br />

are cornered. They defend themselves vigorously and may even attack humans (Danell 1996).<br />

Economic and societal effects (positive/negative)<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> may dig far into the banks of water bodies. Their extended burrowing activity can<br />

cause serious economic damage (undermining of banks, dams, road and railway embankments)<br />

causing their collapse during floods. Also damage to flood protection structures (destabilization of<br />

flood dikes), and to fish farms (chewing through nets and fish traps) have been observed<br />

(Burghause 1996). The system of passages of one O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> family may extend up to 25 m along<br />

the bank and 15 m inland. In Germany the costs of economical impacts caused by O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> are<br />

regarded to be 12,400,000 euros (Reinhardt et al 2003).<br />

O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> may also reduce the ecological value of wetlands of interest to nature conservation<br />

destroying the reed belts, feed on endangered plant species and prey upon rare freshwater bivalves.<br />

The animal moves four times its own weight in gnawed off plants. About a quarter of this is eaten<br />

by the animal, creating quite a lot of dung which usually goes into the water.<br />

In Sweden O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is called a “keystone” species because it creates better living areas for<br />

water fowls and insect as it creates openings in dense vegetation stands and thus prevents lakes<br />

from being overgrown by vegetation (Danell 1996).<br />

Management approaches<br />

Prevention methods<br />

Indications that the spreading of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> would result in serious damages already existed at the<br />

beginning of the 20th century. The first police regulations in Germany on O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> control were<br />

enacted in Saxony and Bavaria in 1917, and provided the basis for the organization of the first<br />

control institutions after World War I (Hoffmann 1958, Burghause 1996). The increasing problems<br />

caused by O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Germany led to the creation of a State Control Service (Reichsbekämpfungsdienst)<br />

in 1933. The State Regulation on O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> Control (Reichsverordnung zur<br />

Bekämpfung der Bisamratte) came into effect on July 1 st 1938, based on the Act for the Protection<br />

of Cultivated Plants (Gesetz zum Schutze der Kulturpflanzen) of 5 May 1937.<br />

The Bern Convention on the Preservation of European Wild Plants and Animals and their Natural<br />

Habitats lists O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Recommendation No. 77 among those species which demonstrably<br />

pose a threat to biological diversity, and therefore recommends its extermination. However,<br />

Burghause (pers. comm.) asserts that it has been obvious for decades that an extermination of O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong> is no longer possible, not even at considerable effort.<br />

According to Estonian List of Invasive Alien Species (Ordinance of the Minister of Environment,<br />

no 126 of 7th Oct. 2004) it is forbidden to bring O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in the country for artificial breeding<br />

or keeping. In the Nature Conservation Law in §49 and §57. cases are described where particular<br />

prevention actions should take place (considering the problems of (invasive) species and their<br />

massive distribution.<br />

Eradication, control and monitoring efforts<br />

7

The choice of the control method depends on the specific features of the problem and the<br />

characteristics of the impacted area.<br />

In some countries the control of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is no longer focused on the extermination of the<br />

species, which is judged impossible. Instead, it is targeted at slowing down the rate of spreading and<br />

at controlling the population size in critical situations. By these measures, Rhineland-Palatinate has<br />

succeeded in preventing serious O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> damage, according to Burghause (1996). However,<br />

statewide control in Germany of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> was only regarded as a reasonable task as long as<br />

there was hope of keeping certain areas pest-free (Burghause, pers. comm.).<br />

Direct control of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> in Germany, for example, has been conducted with traps (cf. Bothe<br />

1993), poisoned bait (chlorphacinon), ferrets, poison gas, and firearms (Burghause 1996).<br />

In the Netherlands O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> are caught in underwater traps constructed to make entry easy but<br />

exit difficult. The animals drown using this method, but this is accepted in the Netherlands as the<br />

period between when O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> realizing there is no way out and it is drowned within the<br />

internationally accepted time limit. In the Netherlands during the last decade of last century the<br />

number of catches was about 30,000 animals and in 2002, 363.042 O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> were caught<br />

(Landelijk Jaarverslag 2002).<br />

In Sweden, trapping of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> has been insignificant due to the low price of O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> furs<br />

and the banning of leghold traps. Furthermore, the species has not been regarded as a “pest” animal<br />

in Sweden and therefore there have been no campaigns to reduce their numbers (Danell 1996).<br />

In Estonia O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is a hunting object, which can be also considered as a controlling method.<br />

According to the Hunting Law in Poland, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> occurring in fish ponds can be shot<br />

throughout the year. Outside fish ponds, the species can be hunted between 11.04 and 15.04 (Polish<br />

Alien Species Database). In Latvia, according to Hunting Law, O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> can be shot from<br />

October 1 st – March 31 st and in unlimited numbers. In the open season of year 2004/2005, 69 O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong> were caught in Latvia.<br />

According to Burghause (1996), the "most successful, but also the most expensive" form of O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong> indirect control is fortification of the embankments. The banks of water bodies are<br />

protected against O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> essentially by inserting a layer of plastic foil. These sections are<br />

additionally reinforced with a strong layer of large stones.<br />

Information and awareness<br />

In Estonia two booklets introducing invasive species of local importance have been published<br />

(Kukk et al 2001, Kull et al. 2005.). The purpose of those booklets is to make the wider range of<br />

people aware of the problems going hand-in-hand with the spread of invasive species. The booklet<br />

also aims to show how the species look and to explain how the spread of species could be<br />

controlled.<br />

Knowledge and research<br />

In Denmark registration of the O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> distribution has taken place with the use of O.<br />

<strong>zibethicus</strong> rafts (Ramsgaard 2005, Ramsgaard and Christensen 2006). In Norway, there are no<br />

recent mappings of the O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> distribution and no analyses of the dispersal rate during<br />

different periods (Danell 1996).<br />

Recommendations or comments from experts and local communities<br />

A monitoring program for O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> is recommended. It should focus on the maximum population<br />

density attained in the absence of control measures, and on the efficacy of predation by mink<br />

(Mustela vison). Lauenstein (pers. comm.) expects that some government agencies may reassess<br />

their position in the next few years, because the widespread lack of control activities could result in<br />

8

a serious aggravation of the O. <strong>zibethicus</strong> problem. Furthermore a better co-operation between the<br />

implicated countries is needed to collect better knowledge of the species (Nanna R. Ramsgaard,<br />

pers. comm.).<br />

References and other resources<br />

Contact persons<br />

Nikolai Laanetu (EE) Centre of Forest Protection and Silviculture, Iva 12, 12618 Tallinn, Tel: +372<br />

6 771 301, Fax: +372 6 771 300, E-mail: nlaanetu@hotmail.com<br />

Frank Klingenstein (DE) Bundesamt für Naturschutz (Federal Agency for Nature Conservation)<br />

Konstantinstraße 110 53179 Bonn -- www.bfn.de Tel.: ++49(0)228/8491-264, Fax: -119, E-mail:<br />

frank.klingenstein@bfn.de<br />

Pall Hersteinsson (IS) PhD, Professor of Mammalogy, Institute of Biology, University of Iceland,<br />

Sturlugata 7, IS-101 Reykjavik, Iceland, Tel.: +354-535 4608, E-mail: pher@hi.is<br />

Petri Nummi (FI) Lecturer in wildlife ecology and management, Department of applied biology<br />

FIN-00014, University of Helsinki, Tel: +358 9 191 58366, E-mail: petri.nummi@helsinki.fi<br />

Wojciech Solarz (PL) Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences Mickiewicza<br />

33, 31-120 Krakow, Poland, Tel. +48 609 440 104 E-mail: solarz@iop.krakow.pl<br />

Thomas Secher Jensen (DK) Aarhus Universitet, Naturhistorisk Museum, Universitetsparken,<br />

Bygning 210, DK-8000 århus C, Tel:. +45 86 12 97 77, E-mail:<br />

Thomas.Secher.Jensen@nathist.au.dk<br />

Nanna R. Ramsgaard (DK) Tordenskjoldsgade 29 st th. 8200 Århus N Tel.: Tel. 87390069, E-mail:<br />

bisam@somewhere.dk<br />

Steinar Wikan (NO) Svanhovd Environmental Centr, N-9925 Svanvik, Tel. (+47) 78 97 36 00, Email:<br />

svanhovd@svanhovd.no<br />

Jānis Ozoliņš (LV) State forest service, Department of hunting, Rīga, 13 janvāra Str. – 15, LV-<br />

1932, Tel: +371 7212776, E-mail: janis.ozolins@vmd.gov.lv<br />

Kjell Danell (SE) Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Animal Ecology,<br />

Tel: +46 70 3747974, E-mail: Kjell.Danell@szooek.slu.se<br />

Johan Danielsen (NO) Directorate for Nature Management, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim,<br />

Norway, Tel.: + 47 73580 949, E-mail: Johan.Danielsen@dirnat.no<br />

Andrey Warshavsky (RU) Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of<br />

Sciences, Moskow, Leninskij pros., 33, Russia. Tel.:495 1247932. E-mail: Warsh@yandex.ru<br />

Links<br />

A review of European mink (Mustela lutreola)<br />

Polish Alien Species database<br />

Bisamrotte – Registreringer i Pasvik Naturreservat 1994-2000<br />

9

References<br />

Artimo, A. 1960. The dispersal and acclimatization of the <strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica (L.), in Finland. Papers on Game Res. 21:<br />

1-101. Helsinki.Banfield, A. W. F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. – University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada,<br />

438 pp.<br />

Barthelmes, D. 1991. Schwere Fraßschäden durch Bisamratten (<strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica L.) als Ursache für den<br />

Gelegerückgang in mitteleuropäischen Seen. – Arch. Natursch. Landschaftsforsch. 31(1): 3-18.<br />

Baumann, A. and R. Everding .1986. Schädling in Naturschutzgebieten. – Der Bisamjäger 21: 9.<br />

Bernhardt, K. G., Schröpfer, R.1992. Einfluß des Bisams auf die Vegetation - Untersuchungen im Ersatzbiotop Geeste<br />

im Emsland. Naturschutz und Landschafts-planung 1/92: 20-26<br />

Bothe, C. 1993. Über die Wirksamkeit, Zuverlässigkeit, Norwendigkeit und Tierschutzgerechtigkeit von Bisamfallen<br />

und Fangmethoden. Unveröff. Diplomarbeit, Braunschweig.<br />

Brander, T. 1955. Über die Bisamratte, <strong>Ondatra</strong> z. zibethica (L.) als Vernichter von Najaden. – Arch. f. Hydrobiol.<br />

50(1): 92-103.<br />

Burghause, F. 1988. Der Bisam – vom Pelztier zum Schädling. – In: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz (ed.),<br />

„Einwanderer“ – Zur Geschichte und Biologie eingeschleppter und eingewanderter Arten in Rheinland-Pfalz. I.:<br />

Säugetiere, 27-37. Mainz (=Mainzer Naturwissenschaftliches Archiv, Beiheft 10).<br />

Burghause, F. 1996. 40 Jahre Bisam in Rheinland-Pfalz. Die Bedeutung eines eingewanderten Nagers und die<br />

Bemühungen, seinen Schaden einzudämmen. – Mainzer naturwiss. Archiv 34: 119-138.<br />

Böhmer, H.J., Heger, T., Trepl, L. 2001. Fallstudien zu gebietsfremden<br />

Arten in Deutschland - Case studies on Aliens Species in Germany. – Texte des Umweltbundesamtes 2001 (13),<br />

126pp.<br />

Danell, K. 1977. Short-term plant succession for following the colonization of a northern Swedish lake by O. zibethica,<br />

- J. APPL. ECOL. 14: 933-947.<br />

Danell, K. 1979. Reduction of aquatic vegetation following the colonization of a northern Swedish lake by the O.<br />

zibethica, – OECOLOGIA 38: 101-106.<br />

Danell, 1996 – introduction of aquatic rodents: lessons of the <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong> invasion, Wildlife biology 2: 213-220.<br />

Diemer, B. 1996. Der Bisam (<strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>) in Baden-Württemberg. - In: Verein der Freunde und Förderer der<br />

Akademie für Natur- und Umweltschutz (Umweltakademie) beim Ministerium für Umwelt und Verkehr Baden-<br />

Württemberg (Hrsg.), Neophyten, Neozoen – Gefahr für die heimische Natur?, 182-186. Stuttgart (= Beiträge der<br />

Akademie für Natur- und Umweltschutz Baden-Württemberg 22).<br />

Heidecke, D. and Seide, P. ca. 1986. Bisamratte <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong> (L.). In: Buch der Hege, 640-666.<br />

Hochwald, S. 1990. Bestandsgefährdung seltener Muschelarten durch den Bisam (<strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica). – Schriftenr.<br />

Bayer. Landesamt für Umweltschutz 97: 113-114.<br />

Hoffmann, M. 1958. Die Bisamratte – ihre Lebensgewohnheiten, Verbreitung, Bekämpfung und wirtschaftliche<br />

Bedeutung. – Leipzig 1958.<br />

Kintzel, W. 1985. Die Besiedlung des Kreises Lübz durch die Bisamratte (<strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica). – Säugetierkd. Inf. Jena<br />

2(9): 277-281.<br />

Kirchner, H.-A. 1954. Das Vordringen der Bisamratte nach Mecklenburg. – In: Archiv der Freunde der Naturgeschichte<br />

in Mecklenburg, Bd. 1, 118-124.<br />

Krauss, M. 1990. Die Nahrung des Bisams (<strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>) an der Havel in Berlin-West und der schädigende<br />

Einfluß auf das Röhricht. – Landschaftsentw. u. Umweltforschung 71: 141-181.<br />

Kukk, T., Kull, T., Lilleleht, V., Ojaveer, H. 2001. Võõrliigid Eestis. Keskkonnaministeerium. Tallinn. Estonia.<br />

Kull, T., Kukk, T., Kangur, M. et al. 2005. Invasiivsed võõrliigid Eestis. Keskkonnaministeerium. Tallinn. Estonia. (In<br />

Estonian)<br />

Landelijk Jaarverslag 2002 Muskusrattenbestrijding – Web-version<br />

Lavrov, N.P. 1957. Akklimatizatsija ondatrõ v SSSR. Izdatelstvo Tsentrosojuz, Moskva. 531 s.<br />

Liljeström, G. 1954: Bisam I Norrbotten. – Svensk Jakt 92: 341. (In Swedish).<br />

Lund, E. and S. Wikan 1995: The <strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica L. established in Norway. Fauna 48: 114-122.<br />

Meinert, G. and Diemer, B. 1977. Die Vermehrung des Bisams in Abhängigkeit von der Wassertemperatur. – Gesunde<br />

Pflanze 28 (9): 200-202.<br />

Ramsgaard, Nanna R. (2005): Bisamrotten (<strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>) i Danmark - Status og konsekvensanalyse af<br />

bisamrottens udbredelse i Danmark. Unpubl. M.Sc. thesis. Univ.Aarhus, Denmark.<br />

Nummi, P., Väänanen, V-M. and Malinen, J. 2005. Alien grazing: Indirect effects of muskrats on invertebrates. – Biol.<br />

Invasions. In press.<br />

Ozols G. 1997. <strong>Ondatra</strong>, bizamžurka (<strong>Ondatra</strong> zibethica). Enciklopēdija Latvijas daba. 4. Rīga, Preses nams, 55 - 56<br />

10

Pietsch, M. 1982. <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong> (Linnaeus, 1766) – Bisamratte, Bisam. – In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp, Handbuch<br />

der Säugetiere Europas, Bd. 2/I, 177-192. Wiesbaden.<br />

Ramsgaard N. R. and Christensen, J.T. 2006. Bisamrotten (<strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong>) I Danmark: Status 2005 (with english<br />

summary: Distribution of the muskrat in Denmark: Status 2005). Flora of Fauna 112(1): 20-24.<br />

Reinhardt, F., Herle, M., Bastiansen, F., Streit, B. 2003. Economic Impact of the Spread of Alien Species in Germany.<br />

pp 183<br />

Rintanen, T. 1976. Lake studies in eastern Finnish Lapland. I. Aquatic flora: Phanerograms and Charles. – Ann. Bot.<br />

Fennici 13: 137-148.<br />

Schröpfer, H. & C. Engstfeld. 1983. Die Ausbreitung des Bisams <strong>Ondatra</strong> <strong>zibethicus</strong> (Linné 1766, Rodentia<br />

Arvicolidae) in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. – Z. angew. Zool. 70: 13-37.<br />

Semjonov-Tian-Sjanskij, O. 1987: Pattedyrene på Kola. – Rapport fra Fylkesmannen i Finnmark, (Vadsö, Norway) 25:<br />

1-129. (In Norwegian).<br />

Stubbe, M. 1993. Mustela vison – Mink. – In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp (ed.), Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas. Band<br />

5: Raubsäuger – Carnivora (Fissipedia). Wiesbaden.<br />

Ulbrich, J. ca. 1928. Die Bisamratte – Lebensweise, Gang ihrer Ausbreitung in Europa, wirtschaftliche Bedeutung und<br />

Bekämpfung. – Dresden.<br />

Zimmermann, U., Gorlach, J., Ansteeg, O. and U. Bossneck 2000. Bestandsstützungsmaßnahme für die Bachmuschel<br />

(Unio crassus) in der Milz (Landkreis Hildburghausen). – Landschaftspflege und Naturschutz in Thüringen 37(1):<br />

11-16.<br />

Корсакова И. Б., Тимофеев В. В., Сафонов В. Г. Акклиматизация охотничье-промысловых зверей и птиц в<br />

СССР, ч. 1. – Киров. – 1973. – 536 с. (Acclimatization game animals and birds in the USSR. Kirov, 1973, part<br />

1: 536).<br />

Соколов В. Е., Лавров Н. П. (Отв. ред.). 1993.. Ондатра. Морфология, систематика, экология. М.: Наука. 542 с.<br />

(Sokolov V.E., Lavrov N.P. The muskart. Morphology, Systematics, Ecology. Nauka Publishers, Moscow 1993.<br />

542 p.<br />

Date of creation/modification of this species fact sheet: 05-02-2008<br />

11