field guide to the amphibians and reptiles of arusha national park

field guide to the amphibians and reptiles of arusha national park

field guide to the amphibians and reptiles of arusha national park

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

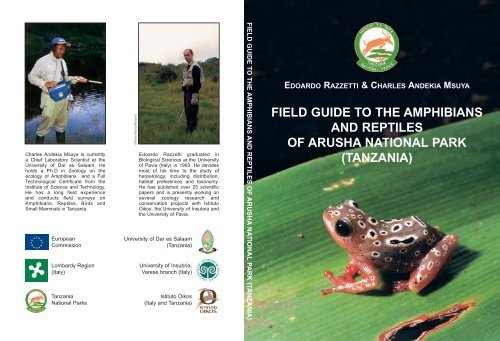

Charles Andekia Msuya is currently<br />

a Chief Labora<strong>to</strong>ry Scientist at <strong>the</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Dar es Salaam. He<br />

holds a Ph.D in Zoology on <strong>the</strong><br />

ecology <strong>of</strong> Amphibians <strong>and</strong> a Full<br />

Technological Certificate from <strong>the</strong><br />

Institute <strong>of</strong> Science <strong>and</strong> Technology.<br />

He has a long <strong>field</strong> experience<br />

<strong>and</strong> conducts <strong>field</strong> surveys on<br />

Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds <strong>and</strong><br />

Small Mammals in Tanzania.<br />

European<br />

Commission<br />

Lombardy Region<br />

(Italy)<br />

Tanzania<br />

National Parks<br />

(Pho<strong>to</strong> Paola Mariani)<br />

Edoardo Razzetti graduated in<br />

Biological Sciences at <strong>the</strong> University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Pavia (Italy) in 1993. He devotes<br />

most <strong>of</strong> his time <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> study <strong>of</strong><br />

herpe<strong>to</strong>logy, including distribution,<br />

habitat preferences <strong>and</strong> taxonomy.<br />

He has published over 25 scientific<br />

papers <strong>and</strong> is presently working on<br />

several zoology research <strong>and</strong><br />

conservation projects with Istitu<strong>to</strong><br />

Oikos, <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Insubria <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Pavia.<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Dar es Salaam<br />

(Tanzania)<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Insubria,<br />

Varese branch (Italy)<br />

Istitu<strong>to</strong> Oikos<br />

(Italy <strong>and</strong> Tanzania)<br />

FIELD GUIDE TO THE AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES OF ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK (TANZANIA)<br />

EDOARDO RAZZETTI & CHARLES ANDEKIA MSUYA<br />

FIELD GUIDE TO THE AMPHIBIANS<br />

AND REPTILES<br />

OF ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK<br />

(TANZANIA)

FIELD GUIDE TO THE AMPHIBIANS<br />

AND REPTILES<br />

OF ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK (TANZANIA)<br />

The publication <strong>of</strong> this book has been made possible through contributions from:<br />

European Commission<br />

Lombardy Region (Italy)<br />

Tanzania National Parks<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Dar es Salaam (Tanzania)<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Insubria, Varese branch (Italy)<br />

Istitu<strong>to</strong> Oikos (Italy <strong>and</strong> Tanzania)

Primary forest on <strong>the</strong> slopes <strong>of</strong> Ngurdo<strong>to</strong> crater.

EDOARDO RAZZETTI & CHARLES ANDEKIA MSUYA<br />

FIELD GUIDE TO THE AMPHIBIANS<br />

AND REPTILES<br />

OF ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK<br />

(TANZANIA)

Acknowledgements:<br />

The study <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> amphibian <strong>and</strong> reptile populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park has<br />

been carried out in <strong>the</strong> framework <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mount Meru Conservation Project (2000-<br />

2002), a joint effort <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Insubria, Varese branch, Tanzania National<br />

Parks (TANAPA) <strong>and</strong> Istitu<strong>to</strong> Oikos, funded by <strong>the</strong> European Union. The publication<br />

<strong>of</strong> this <strong>guide</strong>book, that includes <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> two <strong>field</strong> campaigns, has been possible<br />

thanks also <strong>to</strong> financial contributions by <strong>the</strong> Lombardy Region (Italy). The authors are<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore grateful <strong>to</strong> all <strong>the</strong> above mentioned institutions for <strong>the</strong>ir support.<br />

They extend especial thank <strong>to</strong> TANAPA for granting permission <strong>to</strong> work in <strong>the</strong> <strong>park</strong>, <strong>to</strong><br />

Arusha National Park’s staff, for its guidance, cooperation <strong>and</strong> assistance in <strong>the</strong> <strong>field</strong>,<br />

Istitu<strong>to</strong> Oikos <strong>and</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Insubria staff for co-ordination <strong>and</strong> logistic.<br />

We are also grateful <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> many people who have contributed <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> completion <strong>of</strong><br />

this book, <strong>and</strong> particularly <strong>to</strong>: Pr<strong>of</strong>. Kim M. Howell for confirming <strong>the</strong> identifications;<br />

Rossella Rossi for <strong>the</strong> co-ordination <strong>and</strong> enthusiastic support; Paola Mariani for<br />

preparing <strong>the</strong> distribution maps <strong>and</strong> carrying bags full <strong>of</strong> venomous snakes in her car;<br />

Paola Codipietro, Valeria Galanti, Silvia Porrini, Cesare Puzzi, Stefania Trasforini <strong>and</strong><br />

Archiebald Temu for <strong>the</strong>ir assistance during <strong>field</strong>work; Donald G. Broadley, John<br />

Poyn<strong>to</strong>n <strong>and</strong> Guido Tosi for <strong>the</strong> invaluable help on <strong>the</strong> revision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text <strong>and</strong> scientific<br />

support; Franco Andreone, Michael Lambert, Ronald A. Nussbaum, Jens<br />

Boedtker Rasmussen, Sebastiano Salvidio, Stefano Scali, Rober<strong>to</strong> Sindaco, Richard<br />

Wahlgren <strong>and</strong> Martin Whiting for <strong>the</strong>ir useful suggestions <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> bibliographic material,<br />

Stephen Spawls <strong>and</strong> Michele Menegon for providing some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> excellent slides<br />

<strong>and</strong> finally Josephine Driessen for <strong>the</strong> editing.<br />

Front cover: Hyperolius viridiflavus<br />

© Copyright 2002 TANAPA<br />

Text by: Edoardo Razzetti <strong>and</strong> Charles Andekia Msuya<br />

Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy: All pho<strong>to</strong>graphs by Edoardo Razzetti with <strong>the</strong> following exceptions:<br />

pages 42 <strong>and</strong> 47 by Michele Menegon, pages 43, 44, 64 <strong>and</strong> 70 by<br />

Stephen Spawls.<br />

Maps by: Paola Mariani<br />

All rights reserved - Printed in Varese, Italy

CONTENTS<br />

FOREWORD by Lota Melamari<br />

(Direc<strong>to</strong>r General Tanzania National Parks) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7<br />

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> booklet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Arusha National Park . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<br />

Arusha National Park <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13<br />

Data collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<br />

Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16<br />

LIST OF SPECIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

Bufo gutturalis (Guttural Toad) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19<br />

Xenopus muelleri (Mueller’s Clawed Frog) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20<br />

Ptychadena mascareniensis (Mascarene Grass Frog) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22<br />

Rana angolensis (Common River Frog) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24<br />

Strongylopus fasciatus merumontanus (Striped Long-<strong>to</strong>ed Frog) . . . . . . 26<br />

Phrynobatrachus keniensis (Puddle Frog) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28<br />

Hemisus marmoratum (Mottled Shovel-nosed Frog) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30<br />

Kassina senegalensis (Bubbling Kassina) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32<br />

Hyperolius viridiflavus omma<strong>to</strong>stictus (Painted Reed Frog) . . . . . . . . . . 34<br />

Hyperolius nasutus (Long Reed Frog) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36<br />

Geochelone pardalis babcocki (Tropical Leopard Tor<strong>to</strong>ise) . . . . . . . . . . 37<br />

Hemidactylus mabouia (Tropical House Gecko) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38<br />

Pachydactylus turneri (Bibron’s Thick-<strong>to</strong>ed Gecko) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39<br />

Keys for <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chameleons<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arusha National Park . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40<br />

Bradypodion tavetanum (Kilimanjaro Two-horned Chameleon) . . . . . . . 41<br />

Chamaeleo dilepis (Common Flap-necked Chameleon) . . . . . . . . . . . . 42<br />

Chamaeleo gracilis (Gracile Chameleon) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43<br />

Chamaeleo rudis (Ruwenzori Side-striped Chameleon) . . . . . . . . . . . . 44<br />

Chamaeleo jacksonii merumontanus<br />

(Meru Three-horned Chameleon) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46<br />

Agama agama (Rock Agama) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48<br />

Mabuya striata (Eastern Striped Skink) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50<br />

Mabuya varia (Variable Skink) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51<br />

Lygosoma afrum (Peter’s Writhing-skink) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52<br />

Panaspis wahlbergii (Wahlberg’s Snake-eyed Skink) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53<br />

5

Adolfus jacksoni (Jackson’s Forest Lizard) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54<br />

Nucras boulengeri (Boulenger’s Scrub-lizard ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55<br />

Lep<strong>to</strong>typhlops scutifrons merkeri (Merker’s Worm-snake) . . . . . . . . . . . 56<br />

Python natalensis (Sou<strong>the</strong>rn African Python) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58<br />

Bitis arietans (Puff Adder) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60<br />

Elapsoidea loveridgei loveridgei (Loveridge’s Garter Snake) . . . . . . . . . 62<br />

Naja haje (Egyptian Cobra) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63<br />

Dendroaspis angusticeps (Green Mamba) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64<br />

Lamprophis fuliginosus (Brown House-snake) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65<br />

Lycophidion capense jacksoni (Jackson’s Wolf-snake) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66<br />

Psammophis phillipsii (Olive Grass Snake) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67<br />

Natriciteres olivacea (Olive Marsh-snake) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68<br />

Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia (White-lipped Snake) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69<br />

Thelo<strong>to</strong>rnis mossambicanus (Mozambique Twig Snake) . . . . . . . . . . . . 70<br />

Dasypeltis scabra (Common Egg-eater) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71<br />

OTHER SPECIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73<br />

CHECK LIST OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES<br />

AT THE ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75<br />

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79<br />

6

FOREWORD<br />

The breathtaking scenery <strong>of</strong> Mount Meru <strong>and</strong> Kilimanjaro is not <strong>the</strong> only reason<br />

for visiting Arusha National Park. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> extraordinary quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>park</strong> lies in <strong>the</strong> variety <strong>of</strong> its l<strong>and</strong>scapes <strong>and</strong> habitats, ranging from open<br />

savannah <strong>to</strong> montane forests, lakes, marshes <strong>and</strong> rocky peaks, hosting a<br />

highly diverse wildlife community. Therefore visi<strong>to</strong>rs, during <strong>the</strong>ir walks<br />

through <strong>the</strong> <strong>park</strong>, besides enjoying <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> an elephant roaming in <strong>the</strong> forest,<br />

have <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>to</strong> discover <strong>the</strong> enchanting world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> minor<br />

species: birds, butterflies, frogs, snakes. The Arusha National Parks herpe<strong>to</strong>fauna<br />

seems <strong>to</strong> be particularly interesting <strong>and</strong> diverse.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> last 50 years many species <strong>of</strong> <strong>amphibians</strong> throughout <strong>the</strong> world have<br />

declined markedly in numbers, also within apparently pristine habitats, such<br />

as <strong>national</strong> <strong>park</strong>s <strong>and</strong> nature reserves. Concern is so high that <strong>the</strong> Species<br />

Survival Commission <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Inter<strong>national</strong> Union for <strong>the</strong> Conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

Nature (IUCN) established <strong>the</strong> Declining Amphibian Populations Task Force<br />

<strong>to</strong> collect <strong>and</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r data on amphibian populations <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> assess <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

geographic distribution, <strong>the</strong>ir decline <strong>and</strong> possible causes. In order <strong>to</strong> contribute<br />

<strong>to</strong> this inter<strong>national</strong> effort, TANAPA decided <strong>to</strong> ga<strong>the</strong>r updated information<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park herpe<strong>to</strong>fauna <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> keep moni<strong>to</strong>ring its<br />

populations.<br />

This booklet is <strong>the</strong> result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> joint effort <strong>of</strong> two naturalists: Charles Msuya<br />

from <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Dar es Salaam <strong>and</strong> Edoardo Razzetti from <strong>the</strong><br />

University <strong>of</strong> Pavia. They have been working within <strong>the</strong> framework <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Mount Meru Conservation Project (2000-2002), a joint effort <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University<br />

<strong>of</strong> Insubria, Varese branch, Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) <strong>and</strong> Istitu<strong>to</strong><br />

Oikos, funded by <strong>the</strong> European Union <strong>and</strong> aimed at studying <strong>and</strong> preserving<br />

<strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park biodiversity. The authors’ competence, commitment<br />

<strong>and</strong> enthusiasm, <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong>ir ability <strong>to</strong> take beautiful pho<strong>to</strong>graphs,<br />

resulted in this fine work, that is expected <strong>to</strong> gently <strong>guide</strong> visi<strong>to</strong>rs in<strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> fascinating world <strong>of</strong> <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong>, two groups <strong>of</strong> animals,<br />

which have been on earth so much longer than man.<br />

LOTA MELAMARI<br />

(Direc<strong>to</strong>r General<br />

Tanzania National Parks)<br />

7

FIELD GUIDE TO THE AMPHIBIANS<br />

AND REPTILES<br />

OF ARUSHA NATIONAL PARK<br />

(TANZANIA)

Aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> booklet<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Tanzania is inter<strong>national</strong>ly recognised as a key country for <strong>the</strong> conservation<br />

<strong>of</strong> African biological diversity. Its herpe<strong>to</strong>fauna numbers about 130 <strong>amphibians</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> over 275 <strong>reptiles</strong>, many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m strictly endemic <strong>and</strong> included in <strong>the</strong><br />

“IUCN” Red lists <strong>of</strong> different countries. This unique resource is still relatively<br />

unknown even if <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> are ideal subjects for zoological<br />

inven<strong>to</strong>ries <strong>and</strong> biogeographical analysis as <strong>the</strong>y are relatively easy <strong>to</strong> survey<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten strictly related <strong>to</strong> a particular environment. Moreover, since<br />

1989 <strong>the</strong> scientific community has started <strong>to</strong> realise that <strong>amphibians</strong> are<br />

declining in many areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world <strong>and</strong> that <strong>the</strong>y are more sensitive than<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r species <strong>to</strong> diverse environmental modifications. This is probably due <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>ir larval <strong>and</strong> adult stages occupy different habitats <strong>and</strong> have<br />

limited vagility (Stebbins & Cohen, 1995; Houlahan et al., 2000).<br />

Despite its importance, <strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park herpe<strong>to</strong>fauna has never<br />

been completely studied up <strong>to</strong> now, even if some scientific papers showed<br />

already its peculiarity <strong>and</strong> importance.<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> this booklet is <strong>to</strong> fill <strong>the</strong> existing gap in <strong>the</strong> literature <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> provide<br />

a stimulus that will streng<strong>the</strong>n ecological <strong>to</strong>urism in <strong>the</strong> <strong>park</strong>. Visi<strong>to</strong>rs will<br />

be encouraged <strong>to</strong> appreciate also this fascinating <strong>and</strong> a bit mysterious component<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ecosystems.<br />

Arusha National Park<br />

Arusha National Park is situated on <strong>the</strong> eastern slopes <strong>of</strong> Mt. Meru in<br />

Tanzania. The area lies on <strong>the</strong> eastern edge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Rift Valley. The<br />

geology <strong>and</strong> soils dominating much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>park</strong> <strong>and</strong> Mt. Meru area are volcanic<br />

by origin, resulting from <strong>the</strong> activity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mountain. The volcanic<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> Mt. Meru began during <strong>the</strong> Pleis<strong>to</strong>cene, forming <strong>the</strong> Meru caldera<br />

<strong>and</strong> several minor craters including Ngurdo<strong>to</strong> Crater. About six thous<strong>and</strong><br />

years ago <strong>the</strong> eastern part <strong>of</strong> Meru caldera collapsed forming an extensive<br />

lahar <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> closed alkaline lakes. The only lake which has an outflow water<br />

system is <strong>the</strong> Small Momela, which empties in<strong>to</strong> Big Momela Lake.<br />

Continued volcanic activity built an ash cone in Meru Crater, an attractive feature<br />

on Mt. Meru. A combination <strong>of</strong> climatic changes <strong>and</strong> river flows have<br />

influenced <strong>the</strong> concentration <strong>of</strong> alkali in <strong>the</strong> lakes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> biological<br />

diversity <strong>and</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> organisms. The highest biological diversity is<br />

found in Lake Longil, which has relatively low alkaline levels.<br />

11

The vegetation <strong>of</strong> Arusha National Park follows an altitudinal zonation<br />

(Hedberg, 1951). The lower altitude (1440-1700 m) vegetation cover varies<br />

from shrubl<strong>and</strong>, thicket <strong>and</strong> bushl<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> dry evergreen forest, where<br />

Diospyros abyssinica (Hiern) <strong>and</strong> Olea hochstetteri Baker are common.<br />

The mid altitude (1700-1800 m) vegetation on Mt. Meru is dominated by an<br />

evergreen mist fed forest, with Olea hochstetteri, Assearis, Cro<strong>to</strong>n, Ficus <strong>and</strong><br />

Nuxia sp. On <strong>the</strong> walls <strong>of</strong> Ngurdo<strong>to</strong> Crater Cassipourea malossana (Baker)<br />

dominates.<br />

The higher altitude (1800-2100 m) forest is dominated by Juniperus,<br />

Podocarpus, Ilex, Xymalos, Afrocrania sp. <strong>and</strong> several epiphytes. Plant communities<br />

around Meru caldera are mainly pioneers.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lakes are very alkaline <strong>and</strong> open with Cyperus leavigatus dominating<br />

at <strong>the</strong> edge. Lake Longil has a less alkaline environment <strong>and</strong> lit<strong>to</strong>ral<br />

vegetation, with Cyperus, Papyrus <strong>and</strong> Typha sp. dominate. The lake is also<br />

covered with Nymphaea caerulea, Cera<strong>to</strong>phyllum demersum <strong>and</strong> Pistia stratiorates.<br />

Pitfall traps at Lokie swamp; many species <strong>of</strong> <strong>amphibians</strong> can be found in this area including:<br />

Xenopus muelleri, Ptychadena mascareniensis, Phrynobatrachus keniensis, Kassina senegalensis,<br />

Hyperolius viridiflavus <strong>and</strong> Hemisus marmoratum.<br />

12

Lokie swamp after heavy rainfalls, hundreds <strong>of</strong> Xenopus muelleri can be found in a single pitfall<br />

trap.<br />

Arusha National Park <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong><br />

The Arusha National Park herpe<strong>to</strong>fauna has never been completely studied<br />

although some specimens were collected in <strong>the</strong> Mt. Meru area during <strong>the</strong><br />

Swedish scientific expedition in East Africa at <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> last century<br />

(Andersson, 1911; Lönnberg, 1910, 1911). Later (1956-1957) some<br />

chameleons <strong>and</strong> a few o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>reptiles</strong> were collected by <strong>the</strong> hunters <strong>and</strong> snake<br />

experts C.J.P. Ionides <strong>and</strong> Lt. Col. J. Minnery (Loveridge, 1959; R<strong>and</strong>, 1958;<br />

1963). Finally, a paper about <strong>the</strong> most common snakes was posthumously<br />

published by <strong>the</strong> Scientific Officer <strong>of</strong> Tanzania National Parks, Desmond<br />

Foster Vesey-FitzGerald (1975).<br />

The Arusha National Park is particularly interesting for <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong><br />

because (1) <strong>the</strong>re are still large areas <strong>of</strong> montane forest, (2) <strong>the</strong> mountain<br />

systems <strong>of</strong> Meru, Kilimanjaro <strong>and</strong> Kenya are quite varied <strong>and</strong> host many<br />

endemic species, (3) <strong>the</strong>re are many different habitats.<br />

Last but not least, Arusha National Park is regularly visited by many <strong>to</strong>urists<br />

interested not only in large mammals, but also in smaller animals such as<br />

birds or butterflies. The opportunity <strong>to</strong> watch some brightly coloured endemic<br />

chameleons (such as Chamaeleo jacksonii merumontanus) or listen <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

13

melodic calls <strong>of</strong> beautiful frogs (like <strong>the</strong> endemic Hyperolius viridiflavus<br />

omma<strong>to</strong>stictus or <strong>the</strong> mountain frog Strongylopus fasciatus merumontanus)<br />

could add value <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Park <strong>and</strong> help people <strong>to</strong> appreciate a different aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> this beautiful protected area.<br />

Data collection<br />

This <strong>guide</strong>book includes <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> a <strong>field</strong> campaign carried out in April-<br />

May 2001. Some scattered data were also collected by one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors<br />

during <strong>the</strong> ichthyological <strong>and</strong> limnological survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>park</strong> in Oc<strong>to</strong>ber-<br />

November 2000.<br />

The methods used <strong>to</strong> collect data on <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> agree with <strong>the</strong><br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard ones proposed by Heyer et al. (1994), Blomberg & Shine (1996)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Halliday (1996). Two trained persons were active for at least 6 hours a<br />

day (day time <strong>and</strong> night time) for 17 days (April-May 2001) always assisted<br />

by three more biologists.<br />

Pho<strong>to</strong>graphs were taken <strong>of</strong> all taxa <strong>to</strong> document <strong>the</strong>ir natural coloration <strong>and</strong><br />

pattern variation. As a fur<strong>the</strong>r aid <strong>to</strong> taxonomic identification <strong>the</strong> acoustic<br />

reper<strong>to</strong>ire <strong>of</strong> some <strong>amphibians</strong> was recorded with a Marantz pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

tape recorder. Voucher specimens were deposited at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Dar es<br />

Salaam <strong>to</strong> confirm identification but this was, if possible, limited <strong>to</strong> specimens<br />

occasionally killed by ants or drowned in <strong>the</strong> traps.<br />

Two main survey techniques were adopted: (1) Drift fences & pitfall traps <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> (2) Systematic Sampling Surveys (time-constrained). Both techniques<br />

were applied in all <strong>the</strong> major natural habitats available in Arusha National<br />

Park.<br />

Drift fences & pitfall traps. Drift fences intercept <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong><br />

moving on <strong>the</strong> ground <strong>and</strong> redirect <strong>the</strong>m in<strong>to</strong> pitfall traps. Four drift fences<br />

were located in different habitat types. Each fence was made from a 60 cm<br />

wide plastic sheeting placed in a 10 cm trench, backfilled with soil <strong>and</strong> fastened<br />

every three meters <strong>to</strong> a staple. The pitfall traps were made from large<br />

plastic buckets (diameter 30 cm, high 40 cm) buried in <strong>the</strong> ground, with <strong>the</strong><br />

opening flush with <strong>the</strong> surface. Fifty meters <strong>of</strong> fencing with 10 traps were<br />

placed near <strong>to</strong> possible amphibian breeding sites (swamps, ponds, streams)<br />

<strong>and</strong> 75 meters <strong>of</strong> fencing with 10 traps in suitable reptile habitats. The traps<br />

were checked every day in <strong>the</strong> morning for seven days <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n moved <strong>to</strong><br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r location.<br />

Pitfall traps are extremely useful <strong>to</strong> obtain information about ground dwelling<br />

<strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong>, but some species are captured more easily than<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs: <strong>amphibians</strong> that are strong jumpers or climbers (like Ptychadena or<br />

Hyperolius) or large <strong>reptiles</strong> (large snakes) are more difficult <strong>to</strong> trap.<br />

Systematic Sampling Surveys (time-constrained). This is an opportunistic<br />

search for <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> with <strong>the</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> finding as many species<br />

as possible. Before each search, <strong>the</strong> exact locality, latitude <strong>and</strong> longitude,<br />

14

Lake Longil during <strong>the</strong> wet season with Kilimanjaro on <strong>the</strong> background.<br />

date, number <strong>of</strong> observers, wea<strong>the</strong>r conditions, temperature, habitat type,<br />

vegetation, slope <strong>and</strong> starting time were recorded. When a habitat had been<br />

adequately sampled in <strong>the</strong> judgement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> investiga<strong>to</strong>r (i.e. when <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

area had been thoroughly investigated or when no new species had been<br />

located within a given period <strong>of</strong> time), <strong>the</strong> finishing time was recorded <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

observers moved <strong>to</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r location. This technique is very useful, making it<br />

possible <strong>to</strong> obtain quantitative values as percentage composition <strong>of</strong> species<br />

<strong>and</strong> numbers seen per man-hour <strong>of</strong> searching.<br />

Secretive species were sought in <strong>the</strong>ir refuges (e.g., under s<strong>to</strong>nes, tree barks<br />

or fallen logs, in leaf litter or among <strong>the</strong> branches <strong>of</strong> trees). Night searches<br />

were carried out with <strong>the</strong> aid <strong>of</strong> head-lamps <strong>and</strong> flashlights. The calls <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>amphibians</strong> at breeding sites were used <strong>to</strong> detect different species (sometimes<br />

<strong>the</strong>y can be heard up <strong>to</strong> 2 km away) <strong>and</strong> traced <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir source when a<br />

“different” call was heard. Specific searching techniques were applied <strong>to</strong> find<br />

some taxa (Caecilians, Chameleons). Different kinds <strong>of</strong> stake nets were used<br />

<strong>to</strong> catch adult <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> tadpoles; fishing rods with slip knots were<br />

used <strong>to</strong> noose lizards, agamas <strong>and</strong> skinks; thick lea<strong>the</strong>r gloves <strong>and</strong> boots,<br />

hooks, <strong>to</strong>ngs <strong>and</strong> “T” shaped sticks helped <strong>to</strong> catch snakes.<br />

15

Results<br />

During <strong>the</strong> herpe<strong>to</strong>logical survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park 10 species <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> 24 <strong>of</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> were found. Analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> data collected<br />

shows that <strong>the</strong> survey allowed us <strong>to</strong> do a complete (or almost complete)<br />

check list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>amphibians</strong>, but <strong>the</strong> accumulation graphs for <strong>the</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> indicate<br />

that a few species are still lacking <strong>and</strong> more research is needed <strong>to</strong> complete<br />

<strong>the</strong> list. This is due <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> limited time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> survey <strong>and</strong> also because<br />

<strong>the</strong> rainy season is optimal for <strong>the</strong> amphibian census, but is also <strong>the</strong> worst<br />

period <strong>to</strong> look for <strong>reptiles</strong> due <strong>to</strong> cold wea<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> high grasses. In particular<br />

most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> large snakes were probably hibernating. We were unable <strong>to</strong><br />

observe any large pythons, for example, during <strong>the</strong> survey, whereas in<br />

Oc<strong>to</strong>ber <strong>and</strong> November many specimens had been found.<br />

16

LIST OF SPECIES

The species accounts are based on <strong>the</strong> following references except where<br />

noted:<br />

Common names for Reptiles are taken from Broadley & Howell (1991),<br />

Loveridge (1957) <strong>and</strong> Branch (1994); for Amphibians from Passmore &<br />

Carru<strong>the</strong>rs (1995), Lambiris (1989b) <strong>and</strong>, for <strong>the</strong> species not listed, from<br />

Frank & Ramus (1996).<br />

Systematics <strong>and</strong> Nomenclature are based on Frost, 1985, 2000, Duellman,<br />

1993, Meirte, 1992 <strong>and</strong> Uetz, 2001 except where noted.<br />

Relevant data about identification, geographic range, ecology <strong>and</strong> reproduction<br />

were taken from (Amphibians): Andersson, 1911; Bowker &<br />

Bowker, 1979; Channing & Griffin, 1993; Duellman & Trueb, 1994; Frost,<br />

2000; Lambiris, 1989a, 1989b; Loveridge, 1925, 1953; Passmore &<br />

Carru<strong>the</strong>rs, 1995; Passmore et al., 1995; Poyn<strong>to</strong>n, 1964; Poyn<strong>to</strong>n &<br />

Broadley, 1985a, 1985b, 1987, 1988, 1991; Rödel, 2000; Schiøtz, 1999;<br />

Stewart, 1967. (Amphibians <strong>and</strong> Reptiles): Barbour & Loveridge, 1928b;<br />

Bauer et al., 1993; Lambert, 1985, 1987; Laurent, 1964; Largen, 1997;<br />

Loveridge, 1935; 1957; Rose, 1962. (Reptiles): Broadley, 1990; Chippaux,<br />

1999, FitzSimons, 1943; Lönnberg, 1911, Loveridge, 1936, 1959; MacKay &<br />

MacKay, 1985; Marais, 1992; Neças, 1999, Pitman, 1974; Schleich et al.,<br />

1996; Uetz, 2001; Vesey-Fitzgerald, 1975.<br />

Notes: Due <strong>to</strong> graphic necessities <strong>the</strong> order in which <strong>the</strong> species are presented<br />

have been slightly modified but a complete systematic check-list has<br />

been added at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> specie accounts.<br />

The synonymies are limited <strong>to</strong> those names that can be found in <strong>field</strong> <strong>guide</strong>s<br />

on African <strong>amphibians</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>reptiles</strong> published in recent years.<br />

18

Bufo gutturalis<br />

Power, 1927<br />

Common names<br />

Guttural Toad, Greater Cross-marked<br />

Toad<br />

Synonyms<br />

Bufo regularis gutturalis Power, 1927<br />

Identification<br />

Bufo gutturalis, as it is common in <strong>the</strong><br />

species <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same genus, is s<strong>to</strong>ut with<br />

short strong limbs <strong>and</strong> reduced webbing<br />

on <strong>the</strong> feet. The skin is rough <strong>and</strong> warty,<br />

granular below; <strong>the</strong>re are two large<br />

prominent para<strong>to</strong>id gl<strong>and</strong>s just behind<br />

<strong>the</strong> eyes. The <strong>to</strong>p <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> snout is typically<br />

marked by four dark patches with a<br />

light cross between <strong>the</strong>m. The ground<br />

colour is usually brown with symmetrically<br />

arranged irregular dark blotches<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten a light vertebral stripe. Some<br />

individuals show a reddish tinge in <strong>the</strong><br />

back <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> legs. This species can grow<br />

up <strong>to</strong> 98 mm <strong>of</strong> length but <strong>the</strong> biggest<br />

animal we found in Arusha National Park<br />

was just 57.8 mm.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

Eastern <strong>and</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa: from Kenya<br />

southward <strong>to</strong> South Africa including<br />

Botswana, nor<strong>the</strong>rn Namibia <strong>and</strong> eastern<br />

Angola.<br />

Local distribution<br />

The guttural <strong>to</strong>ad is apparently confined<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> lowl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> we found it up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Park Rest House (less than 1700 m). It<br />

is quite common in <strong>the</strong> bushl<strong>and</strong><br />

between Momela Gate <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> shore <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Ngare Nanyuki river but can be<br />

found also in <strong>the</strong> bushl<strong>and</strong> Uwanja wa<br />

Momela <strong>and</strong> between Big <strong>and</strong> Small<br />

Momela lakes.<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

This species lives in open country bushl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong>ten quite far<br />

from wet areas <strong>and</strong> it is not unusual <strong>to</strong><br />

find it on roads, in gardens <strong>and</strong> near <strong>to</strong><br />

human habitations. The diet is wide,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y will eat almost any animal <strong>of</strong> a suitable<br />

size. The call is a deep vibrant<br />

croak.<br />

Reproduction<br />

Breeding usually takes place in permanent<br />

shallow waters; <strong>the</strong> eggs are characteristically<br />

united in paired strings <strong>and</strong><br />

are laid among submerged vegetation.<br />

During our survey in April <strong>and</strong> May we<br />

heard <strong>the</strong> call <strong>of</strong> a few males only one<br />

night in <strong>the</strong> Serengeti Ndogo. We never<br />

observed <strong>to</strong>ads in <strong>the</strong> water <strong>and</strong> we<br />

never caught any Bufo gutturalis in <strong>the</strong><br />

pitfall traps that we put close <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

water. All <strong>the</strong> guttural <strong>to</strong>ads we found in<br />

<strong>the</strong> pitfall traps were caught in open<br />

bushl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> over 75% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m were<br />

juveniles (less than 50 mm <strong>of</strong> length).<br />

19

Xenopus muelleri<br />

(Peters, 1844)<br />

Common names<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Platanna, Mueller’s Clawed Frog<br />

Synonyms<br />

Dactylethra mülleri Peters, 1844<br />

Taxonomy<br />

While Xenopus muelleri has a wide<br />

range <strong>of</strong> distribution in Tanzania <strong>and</strong><br />

Kenya, <strong>the</strong>re is confusion in geographic<br />

distribution with Xenopus laevis. The<br />

species is monotypic.<br />

Identification<br />

The head is small with upwardly directed<br />

eyes, <strong>the</strong> pupil is circular <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is a<br />

short tentacle under each eye; tympanum<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>ngue are lacking. The body is<br />

flattened <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re are sensory lateral<br />

lines organs on <strong>the</strong> sides made by many<br />

tubercles; <strong>the</strong> skin is very slippery.<br />

Fingers lack webbing while <strong>to</strong>es are fully<br />

webbed <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> inner three terminate in<br />

a black claw. The back is usually dark<br />

brown or grey with irregular dark patches,<br />

<strong>the</strong> belly is usually greyish white.<br />

Females can be distinguished by <strong>the</strong><br />

larger skin folds around <strong>the</strong> vent <strong>and</strong> are<br />

usually larger than males. In Arusha<br />

National Park Xenopus muelleri can<br />

reach 82.5 mm <strong>of</strong> body length.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

All sou<strong>the</strong>rn Africa: from Burkina Faso <strong>to</strong><br />

Kenya <strong>and</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a, southward <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Republic <strong>of</strong> South Africa.<br />

Local distribution<br />

Xenopus muelleri is one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most<br />

common <strong>and</strong> widespread species in<br />

Arusha National Park. from <strong>the</strong> open<br />

grassl<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> Serengeti Ndogo up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

wetl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Kilimanjaro view point <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> big pond near Njeku Camp (2519 m).<br />

It can be found both in temporary <strong>and</strong><br />

permanent waters even in some soda<br />

20<br />

lakes like Lek<strong>and</strong>iro <strong>and</strong> Small Momela.<br />

Using a beach seine we caught some<br />

platannas even in <strong>the</strong> muddy waters <strong>of</strong><br />

El Kekho<strong>to</strong>i<strong>to</strong> pond, a place that is<br />

organically enriched by a large herd <strong>of</strong><br />

buffalos <strong>and</strong> a few hippos. The highest<br />

density population is probably located in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Lokie swamp where, using a drift<br />

fence, on a few occasions we caught<br />

over 100 platannas in a single pitfall<br />

trap. Many authors reported <strong>the</strong> presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> Xenopus muelleri in streams<br />

<strong>and</strong> rivers, but we never found any in <strong>the</strong><br />

watercourses <strong>of</strong> Arusha National Park.<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

Platannas are usually restricted <strong>to</strong><br />

aquatic habitats, <strong>the</strong>y move on l<strong>and</strong> during<br />

rainy nights. If <strong>the</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>r is wet<br />

enough <strong>the</strong>y sometimes w<strong>and</strong>er in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

forest or bushl<strong>and</strong>; we observed some <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>m over half a kilometre from <strong>the</strong> nearest<br />

wet zone. During <strong>the</strong> day <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

usually difficult <strong>to</strong> spot, but in pools with<br />

poor oxygen it is possible <strong>to</strong> detect <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

presence by circles in <strong>the</strong> water when<br />

individuals come <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>to</strong> take<br />

air. In <strong>the</strong> night with a lamp it is possible<br />

<strong>to</strong> observe <strong>the</strong>m as <strong>the</strong>y float motionless<br />

in <strong>the</strong> shallow water. Xenopus can feed<br />

both in <strong>the</strong> water <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>; a wide range<br />

<strong>of</strong> arthropods are preyed on but also<br />

small fish <strong>and</strong> even small tadpoles. The<br />

call is a s<strong>of</strong>t buzzing sound uttered<br />

under water by both sexes.

Reproduction<br />

The mating begins immediately after <strong>the</strong><br />

start <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rainy season <strong>and</strong> amplexus<br />

occurs under water. Several thous<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>of</strong> eggs are laid on <strong>the</strong> aquatic vegetation.<br />

The tadpoles are plank<strong>to</strong>n feeders<br />

<strong>and</strong> swim with <strong>the</strong> head directed downward.<br />

The body is almost transparent<br />

with a long tail <strong>and</strong> two sensory tentacles<br />

in <strong>the</strong> mouth region. They somewhat<br />

resemble <strong>the</strong> glass catfish<br />

Kryp<strong>to</strong>pterus bicirrhis, a common<br />

species <strong>of</strong> aquarium fish.<br />

21

Ptychadena mascareniensis<br />

(Duméril <strong>and</strong> Bibron, 1841)<br />

Common names<br />

Mascarene Grass Frog<br />

Taxonomy<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> fact that species <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

genus Ptychadena are common <strong>and</strong><br />

widespread in most <strong>of</strong> Africa <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten very difficult <strong>to</strong> identify.<br />

Identification<br />

A “green frog” with six longitudinal ridges<br />

on <strong>the</strong> back, <strong>and</strong> only <strong>the</strong> outer ones<br />

may be interrupted. This species is<br />

medium sized reaching a snout-vent<br />

length <strong>of</strong> 51 mm (average size <strong>of</strong> adults<br />

in Arusha National Park 25.5 - 30 mm).<br />

Fingers lack webbing <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>es<br />

webbing is present between <strong>the</strong> outer<br />

metatarsals. The back is usually brown<br />

or green with rounded green or brown<br />

blotches usually smaller than <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong><br />

22<br />

<strong>the</strong> eye. There is a light creamy vertebral<br />

b<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> a longitudinal light coloured<br />

line on <strong>the</strong> upper surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tibia.<br />

Males have paired gular slits on <strong>the</strong><br />

sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> throat.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

Widespread in most <strong>of</strong> Africa: from<br />

Sierra Leone <strong>to</strong> Egypt through Eritrea<br />

<strong>and</strong> Ethiopia <strong>to</strong> South Africa; also<br />

Madagascar <strong>and</strong> Seychelles Isl<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

Introduced in<strong>to</strong> Mascarene Isl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Male <strong>of</strong> Mascarene Grass Frog from Kilimanjaro View Point; <strong>the</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vocal sac fold<br />

can be spotted under <strong>the</strong> tympanum.

Female <strong>of</strong> Mascarene Grass Frog from Kilimanjaro View Point almost ready <strong>to</strong> lay <strong>the</strong> eggs.<br />

Local distribution<br />

Widespread <strong>and</strong> abundant in many<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>park</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Mascarene grass<br />

frog is <strong>the</strong> most common amphibian<br />

around <strong>the</strong> brackish waters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Momela lakes (Big <strong>and</strong> Small Momela,<br />

Lek<strong>and</strong>iro). Walking on <strong>the</strong> banks<br />

among <strong>the</strong> reeds it is possible <strong>to</strong> see a<br />

hundred frogs leaping away in <strong>the</strong> water<br />

in less than ten minutes. This species<br />

also inhabits most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ephemeral<br />

ponds in <strong>the</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong>s, for example, in<br />

Serengeti Ndogo <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> small pond<br />

between Lek<strong>and</strong>iro <strong>and</strong> Tulusia lake.<br />

Some specimens were found on <strong>the</strong><br />

shore <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fast flowing stream Ngare<br />

Nanyuki. In Arusha National Park<br />

P. mascareniensis can be found as high<br />

as Kilimanjaro view point <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arched<br />

Fig tree (about 1900 m).<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

Lives in grassl<strong>and</strong>s, wooded grassl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> forest not <strong>to</strong>o far from water. This<br />

species is extremely common in most <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> wet areas as long as it can find<br />

refuge among <strong>the</strong> vegetation. According<br />

<strong>to</strong> Inger <strong>and</strong> Marx (1961) <strong>the</strong> diet consists<br />

mainly <strong>of</strong> terrestrial prey: beetles,<br />

grasshoppers, dragonflies, ants, butterflies<br />

<strong>and</strong> small <strong>amphibians</strong> although<br />

aquatic invertebrates are preyed on as<br />

well. The voice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> male can be heard<br />

both during <strong>the</strong> day <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> night, a<br />

short low pitched nasal “quack” <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

associated by a series <strong>of</strong> clucking<br />

sounds. The males call from a concealed<br />

position in grass or just floating<br />

on <strong>the</strong> surface with open legs.<br />

Reproduction<br />

During <strong>the</strong> rainy season, small pigmented<br />

eggs are laid in a series <strong>of</strong> small<br />

clumps among vegetation in shallow<br />

water. We were not able <strong>to</strong> observe any<br />

oviposition site but at <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong><br />

May we found a few females that looked<br />

almost ready <strong>to</strong> lay.<br />

23

Rana angolensis<br />

Bocage, 1866<br />

Common names<br />

Common River Frog, Angola River Frog<br />

Synonyms<br />

Rana fuscigula angolensis Bocage,<br />

1866<br />

Identification<br />

Alarge “green frog” that can attain in<br />

some areas (Malawi) 90 mm <strong>of</strong> snoutvent<br />

length but usually no more than 70<br />

mm. Skin with incomplete longitudinal<br />

ridges variable in development (cf.<br />

Ptychadena mascareniensis), long legs<br />

(length <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tibia is 55-72% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

snout-vent length). Toes extensively<br />

webbed (cf. Strongylpus fasciatus), fingers<br />

not webbed. Ground colour on <strong>the</strong><br />

back usually green or brown with blotches<br />

about <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eye, a light<br />

green or yellow vertebral line usually<br />

present.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

Upl<strong>and</strong> areas from Ethiopia <strong>to</strong> Angola,<br />

eastward <strong>to</strong> Mozambique, including<br />

most <strong>of</strong> South Africa.<br />

Local distribution<br />

The common river frog in Arusha<br />

National Park can be found both in<br />

24<br />

brackish <strong>and</strong> fresh water, at low altitude<br />

(Maksoro river springs, about 1400 m)<br />

<strong>and</strong> medium altitude (Kilimanjaro View<br />

Point, arched fig tree wet area) up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Maio falls (1926 m).<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

The typical habitat <strong>of</strong> this species are<br />

slow flowing streams with permanent<br />

water. In Arusha National Park most <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> frogs can be found in forested areas<br />

though many can also be observed<br />

among <strong>the</strong> aquatic vegetation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Maksoro river. Rana angolensis has two<br />

distinct calls, a sharp rattle <strong>of</strong> about one<br />

second followed after a short pause by a<br />

short “croak” that resemble <strong>the</strong> call <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> European green frogs Rana synk.<br />

esculenta.<br />

Reproduction<br />

Breeding may occur throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

year; several thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> small pigmented<br />

eggs are laid in shallow water<br />

with a very slow current. The tadpoles <strong>of</strong><br />

Rana angolensis reach a length <strong>of</strong> 80<br />

mm at Gosner’s stage 40. We observed<br />

some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m close <strong>to</strong> metamorphosis at<br />

Kilimanjaro view point at <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> April.<br />

Adult River Frog from<br />

Kilimanjaro View Point.

The wet area at Kilimanjaro View Point; in <strong>the</strong> area it is easy <strong>to</strong> spot: Xenopus muelleri, Rana<br />

angolensis, Strongylopus fasciatus, Ptychadena mascareniensis, Phrynobatrachus keniensis,<br />

Kassina senegalensis <strong>and</strong> Hyperolius viridiflavus.<br />

Only few <strong>amphibians</strong> can survive in <strong>the</strong> soda waters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Small Momela lake: Xenopus<br />

muelleri, Hemisus marmoratum <strong>and</strong> Ptychadena mascareniensis.<br />

25

Strongylopus fasciatus merumontanus<br />

(Lönnberg, 1910)<br />

Common names<br />

Striped Stream Frog, Striped Long-<strong>to</strong>ed<br />

Frog<br />

Synonyms<br />

Strongylopus fasciatus (Smith, 1849)<br />

Taxonomy<br />

Three subspecies are actually considered<br />

valid (Poyn<strong>to</strong>n, 1964): <strong>the</strong> nominal<br />

form, S.f. fuelleborni <strong>and</strong> S.f. merumontanus.<br />

This latter subspecies was<br />

described by Einar Lönnberg from a single<br />

specimen collected on Mt. Meru at<br />

3000 meters during <strong>the</strong> first Swedish<br />

expedition in 1905 (Lönnberg, 1910).<br />

Identification<br />

Snout-vent length up <strong>to</strong> 50 mm (46 mm<br />

in S.f. merumontanus), very similar <strong>to</strong> a<br />

river frog but with extremely long slender<br />

legs <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>es. Webbing absent from fin-<br />

26<br />

gers <strong>and</strong> very reduced on <strong>the</strong> <strong>to</strong>es.<br />

There is a dark stripe on each leg from<br />

<strong>the</strong> knee <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> ankle. The dorsal surface<br />

lacks <strong>the</strong> skin ridges <strong>of</strong> Ptychadena. The<br />

ground colour is usually buff or golden<br />

yellow with conspicuous dark longitudinal<br />

stripes. Some specimens <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mt.<br />

Meru lack <strong>the</strong> dorsal stripes <strong>and</strong> have a<br />

brown-red back.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

Strongylopus fasciatus forms isolated<br />

Strongylopus fasciatus from Kilimanjaro View Point, individual with striped pattern.

Strongylopus fasciatus from <strong>the</strong> same locality, individual with plain reddish back.<br />

populations in <strong>the</strong> mountains from nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Tanzania <strong>to</strong> South Africa, westward<br />

up <strong>to</strong> Zambia <strong>and</strong> eastern Zimbabwe.<br />

This scattered distribution is a clear relict<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cooler periods during <strong>the</strong><br />

Pleis<strong>to</strong>cene when <strong>the</strong>se populations<br />

were linked <strong>to</strong>ge<strong>the</strong>r. Strongylopus fasciatus<br />

merumontanus is endemic in <strong>the</strong><br />

upl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn Tanzania including<br />

Mt. Meru, Uluguru <strong>and</strong> Usumbara Mts.<br />

S.f. fuelleborni occurs in sou<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Tanzania, eastern Zambia <strong>and</strong> Malawi.<br />

S.f. fasciatus is widespread in South<br />

Africa <strong>and</strong> Zimbabwe.<br />

Local distribution<br />

Limited <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> upper meadows <strong>and</strong> open<br />

forested areas <strong>of</strong> Mt. Meru from<br />

Kilimanjaro view point upwards, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

wet areas near <strong>the</strong> arched Fig tree<br />

(about 1900 m) up <strong>to</strong> Njeku camp in <strong>the</strong><br />

caldera (over 2500 m) <strong>and</strong> Ki<strong>to</strong><strong>to</strong> forest.<br />

The species probably occurs also in<br />

higher zones since <strong>the</strong> type specimen <strong>of</strong><br />

S.f. merumontanus has been collected<br />

at 3000 meters.<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

Stream frogs are generally found near<br />

open grassl<strong>and</strong>s within <strong>the</strong> forest, but<br />

during <strong>the</strong> wet season <strong>the</strong>y move in<strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> forest quite far from wet areas. We<br />

observed several young individuals<br />

Strongylopus along <strong>the</strong> road from<br />

Kilimanjaro view point <strong>to</strong> Ki<strong>to</strong><strong>to</strong> forest<br />

view point. Taking pho<strong>to</strong>graphs <strong>of</strong> this<br />

species is quite difficult as <strong>the</strong>y are fast<br />

moving <strong>and</strong> can jump long distances.<br />

The call <strong>of</strong> Strongylopus fasciatus is a<br />

clear high-pitched “pip” uttered singly or<br />

in a short burst <strong>of</strong> three or four; it is quite<br />

difficult <strong>to</strong> distinguish from <strong>the</strong> call <strong>of</strong><br />

Hyperolius viridiflavus.<br />

Reproduction<br />

The eggs are laid singly among vegetation<br />

in shallow waters. During April <strong>and</strong><br />

May on Meru we found many juveniles<br />

<strong>of</strong> about 20 - 25 mm body length. The<br />

reproduction peak probably occurs during<br />

<strong>the</strong> small rains <strong>of</strong> Oc<strong>to</strong>ber <strong>to</strong><br />

December.<br />

27

Phrynobatrachus keniensis<br />

Barbour <strong>and</strong> Loveridge, 1928<br />

Common names<br />

Puddle Frog, Cricket Frog<br />

Taxonomy<br />

This species has been described by<br />

Thomas Barbour <strong>and</strong> Arthur Loveridge<br />

in 1928(a) from a specimen collected in<br />

“a marsh on <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>ast slope <strong>of</strong> Mt.<br />

Kenya, Kenya Colony”. The systematics<br />

<strong>of</strong> puddle frogs is still quite confused<br />

especially in some African regions: “As<br />

long as we lack a thorough revision <strong>of</strong><br />

this genus, <strong>the</strong>se frogs cannot be determined<br />

for certain” (Rödel, 2000).<br />

Identification<br />

In Arusha National Park Phrynobatrachus<br />

keniensis is, along with Hyperolius nasutus,<br />

<strong>the</strong> smallest amphibian species; it<br />

may attain a body length that ranges<br />

Adult Puddle Frog from Mbuga Za Raiden pond.<br />

28<br />

from 14.6 <strong>to</strong> 26 mm (29 individuals<br />

examined). The body is ra<strong>the</strong>r s<strong>to</strong>cky<br />

with short limbs, <strong>the</strong> head is small <strong>and</strong><br />

pointed. The pupil is horizontal <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

tympanum quite small. The most important<br />

diagnostic feature <strong>of</strong> this genus is a<br />

tubercle in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tarsus.<br />

Colour <strong>and</strong> markings are very variable<br />

within <strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park with at<br />

least three different patterns. Ground

Phrynobatrachus keniensis from Kilimanjaru View Point.<br />

colour is usually brown, grey or beige<br />

with a golden tinge. The back can be<br />

uniform, faintly mottled or marked with<br />

dark blotches; some individuals have a<br />

yellow vertebral line extending from<br />

snout <strong>to</strong> vent. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> frogs observed<br />

had a dark lateral b<strong>and</strong> on both sides <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> head <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> flanks.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

Phrynobatrachus keniensis is endemic<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> upl<strong>and</strong> meadows <strong>of</strong> Kenya<br />

(Kikuyu, Molo, Mt. Kinangop, Mt. Kenya)<br />

<strong>and</strong> Mt. Meru.<br />

Local distribution<br />

Common <strong>and</strong> widespread in all <strong>the</strong> wet<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Park especially in grassl<strong>and</strong>s<br />

but also in some forested areas<br />

(Ki<strong>to</strong><strong>to</strong>) from Serengeti Ndogo (1400 m)<br />

up <strong>to</strong> Njeku Camp (over 2500 m). This<br />

species can be observed especially in<br />

<strong>the</strong> small temporary ponds <strong>of</strong> Serengeti<br />

Ndogo <strong>and</strong> near Lokie swamp. We<br />

never found any Phrynobatrachus near<br />

soda lakes <strong>and</strong> brackish streams.<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

Puddle frogs usually live on <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong><br />

swamp, pools <strong>and</strong> streams <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

ready <strong>to</strong> seek refuge in <strong>the</strong> water when<br />

disturbed. They usually move away from<br />

<strong>the</strong> wet areas only after rainfall, but in<br />

<strong>the</strong> meadows inside <strong>the</strong> caldera <strong>of</strong> Meru<br />

<strong>the</strong> average humidity is so high that it is<br />

common <strong>to</strong> find many individuals w<strong>and</strong>ering<br />

around. The voice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> males is<br />

a quick series <strong>of</strong> ticks that resembles <strong>the</strong><br />

sound <strong>of</strong> a coin falling on <strong>the</strong> ground.<br />

Reproduction<br />

Breeding occurs in shallow st<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

waters. The small eggs float in a single<br />

surface layer.<br />

29

Hemisus marmoratum<br />

(Peters, 1854)<br />

Common names<br />

Mottled Shovel-nosed Frog<br />

Synonyms<br />

Engys<strong>to</strong>ma marmoratum Peters, 1854<br />

Kakophrynus sudanensis Steindachner,<br />

1863<br />

Taxonomy<br />

The systematic position <strong>of</strong> Hemisus<br />

marmoratum has been tentatively<br />

revised by Laurent (1972) that recognised<br />

a few subspecies: H.m. marmoratum,<br />

H.m. ingeri, H.m. loveridgei <strong>and</strong><br />

H.m. sudanese.<br />

Identification<br />

Asmall amphibian with short, fat body;<br />

<strong>the</strong> limbs are powerful <strong>and</strong> short, <strong>the</strong><br />

head is small with transverse fold <strong>and</strong><br />

has a pointed snout hardened for digging.<br />

The eyes are small with a vertical<br />

pupil. In Arusha National Park females<br />

reach a snout vent length <strong>of</strong> 35.5 mm<br />

<strong>and</strong> males 29.5 mm (30 individuals<br />

measured). The dorsal colour is usually<br />

brown with a pattern <strong>of</strong> darker reticulation<br />

<strong>and</strong> yellow patches. The throat <strong>of</strong><br />

males is usually grey.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa excluding rainforest<br />

from sou<strong>the</strong>rn Somalia <strong>to</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

South Africa.<br />

Local distribution<br />

The Mottled shovel-nosed frog is quite<br />

common in most grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> open<br />

wooded areas from 1400 <strong>to</strong> 1670 m (we<br />

found it up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> big fig tree near<br />

Leopard Hill View Point on Ngurdo<strong>to</strong><br />

crater). Usually lives near watercourses<br />

(Maksoro, Ngare Nanyuki rivers) <strong>and</strong><br />

most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ponds, swamps <strong>and</strong> even<br />

brackish water lakes (like Big <strong>and</strong> Small<br />

Momela lakes).<br />

30<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

This species is rarely seen as it spends<br />

most <strong>of</strong> its time underground <strong>and</strong> can be<br />

found above <strong>the</strong> surface only during <strong>the</strong><br />

night or in wet wea<strong>the</strong>r. Unlike most<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r burrowing <strong>amphibians</strong><br />

Hemisus burrows headfirst using <strong>the</strong><br />

forelimbs <strong>and</strong> pointed snout <strong>to</strong> penetrate<br />

<strong>the</strong> soil. The prehensile <strong>to</strong>ngue <strong>of</strong><br />

Hemisus marmoratum has a peculiar<br />

structure that allows it <strong>to</strong> be protracted<br />

slowly (increasing capture success) <strong>and</strong><br />

also <strong>to</strong> be elongated hydrostatically <strong>to</strong><br />

double its length during feeding<br />

(Nishikawa et al., 1999). The diet consists<br />

mainly <strong>of</strong> ants <strong>and</strong> termites. Males<br />

call from <strong>the</strong> mouth <strong>of</strong> a small burrow<br />

near water, <strong>the</strong> voice is a repetitive highpitched<br />

buzz that can be confused with<br />

<strong>the</strong> sound produced by crickets.<br />

Reproduction<br />

Eggs are laid in an underground chamber<br />

near water <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> female remains<br />

with <strong>the</strong> brood (Van Dijk, 1997). The tadpoles<br />

develop inside <strong>the</strong> chamber <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>y react very quickly <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> first rains<br />

going in<strong>to</strong> temporary ponds before any<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r species <strong>of</strong> <strong>amphibians</strong>. In Arusha<br />

National Park during April <strong>and</strong> May we<br />

found some tadpoles that were on <strong>the</strong><br />

edge <strong>of</strong> metamorphosis <strong>and</strong> we could<br />

hear very few males calling, so <strong>the</strong><br />

breeding season probably occurs during<br />

<strong>the</strong> small rains period.

Hemisus marmoratum from Momela gate.<br />

Shovel-nosed Frogs call from concealed positions on <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> Lokie swamp.<br />

31

Kassina senegalensis<br />

(Duméril <strong>and</strong> Bibron, 1841)<br />

Common names<br />

Bubbling Kassina, Senegal Running Frog<br />

Synonyms<br />

Cystignathus senegalensis Duméril <strong>and</strong><br />

Bibron, 1841<br />

Taxonomy<br />

Possibly composed <strong>of</strong> various cryptic<br />

species or at least a number subspecies;<br />

Schiøtz (1975) discussed <strong>the</strong><br />

differences in eastern African material<br />

<strong>and</strong> observed four different “forms”<br />

based mainly on dorsal pattern, but<br />

rejected <strong>the</strong> recognition <strong>of</strong> subspecies.<br />

Poyn<strong>to</strong>n & Broadley (1987) concluded<br />

that: “...<strong>the</strong> material appears <strong>to</strong> provide<br />

no clear grounds for <strong>the</strong> separation <strong>of</strong><br />

taxa within <strong>the</strong> senegalensis complex”.<br />

Examination <strong>of</strong> K. senegalensis in <strong>the</strong><br />

Arusha National Park shows both specimens<br />

with Schiøtz’s “Form 1” (pattern<br />

senegalensis) <strong>and</strong> “Form 3” (pattern<br />

argyreivittis).<br />

Identification<br />

Bubbling kassinas are medium sized<br />

frogs reaching a length <strong>of</strong> 44 mm in<br />

Arusha National Park (34 individuals<br />

examined) with short hind legs. Fingers<br />

lack webbing <strong>and</strong> do not bear terminal<br />

discs. The pupil is vertical. The back is<br />

usually bright yellow, khaki or dark<br />

brown (darker individuals are more common<br />

at Njeku camp) with a disruptive<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> longitudinal dark b<strong>and</strong>s that<br />

can be continuous or broken in<strong>to</strong> streaks<br />

<strong>and</strong> oblong spots. Males have a gular<br />

disc <strong>and</strong> a large dark subgular sac divided<br />

in<strong>to</strong> paired lateral pouches.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

African savannas south <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sahara,<br />

from Senegal <strong>and</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Mali <strong>to</strong><br />

Eritrea, Ethiopia <strong>and</strong> Somalia, southward<br />

<strong>to</strong> Namibia <strong>and</strong> South Africa<br />

(excluding <strong>the</strong> western Cape province).<br />

32<br />

Local distribution<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Arusha National Park bubbling<br />

kassinas avoid <strong>the</strong> brackish waters <strong>of</strong><br />

soda lakes but are quite common both in<br />

grassl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> forested areas from <strong>the</strong><br />

lowl<strong>and</strong> temporary ponds in Serengeti<br />

Ndogo (1414 m) up <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Njeku camp<br />

pond (2519 m). Kassinas are good walkers<br />

<strong>and</strong> sometimes single individuals<br />

can be found quite far from wet areas.<br />

We found a few specimen on <strong>the</strong><br />

Ngurdo<strong>to</strong> crater rim <strong>and</strong> a subadult in<br />

s<strong>to</strong>ny bushl<strong>and</strong> about one kilometre from<br />

<strong>the</strong> nearest pond. Lokie swamp, <strong>the</strong> wet<br />

areas near Kilimanjaro View Point <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> rest house ponds are <strong>the</strong> best places<br />

<strong>to</strong> observe this species in <strong>the</strong> Park.<br />

Ecology <strong>and</strong> general behaviour<br />

Even though Kassina senegalensis<br />

belongs <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hyperoliidae family (<strong>the</strong><br />

same as <strong>the</strong> reed frogs) it is a slow moving<br />

ground dwelling species that prefers<br />

<strong>to</strong> walk ra<strong>the</strong>r than jump. During <strong>the</strong> dry<br />

season <strong>the</strong> species seeks refuge under<br />

logs <strong>and</strong> s<strong>to</strong>nes. The voice is an unmistakable<br />

“quoip!” that resembles <strong>the</strong> popping<br />

sound <strong>of</strong> bubbles coming <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> surface.<br />

Males usually call from submerged<br />

vegetation in shallow water during late<br />

afternoon <strong>and</strong> night. Large choruses can<br />

be heard over great distances; during <strong>the</strong><br />

wet season for example <strong>the</strong> large aggregations<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kassinas calling from swamps<br />

<strong>and</strong> ponds inside Ngurdo<strong>to</strong> crater can be<br />

distinctively heard from <strong>the</strong> rim.

Bubbling Kassina from Kilimanjaro View Point.<br />

Reproduction<br />

In Arusha National Park we observed<br />

small clumps <strong>of</strong> eggs on submerged<br />

grass during April <strong>and</strong> May. The tadpoles<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten brightly coloured <strong>and</strong> grow<br />

quite big (usually about 50 mm); <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have broad fins <strong>and</strong> a pointed tail.<br />

Cluster <strong>of</strong> eggs laid by a single kassina at Lokie swamp.<br />

33

Hyperolius viridiflavus omma<strong>to</strong>stictus<br />

Laurent, 1951<br />

Common names<br />

Painted Reed Frog<br />

Taxonomy<br />

The taxonomy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hyperolius viridiflavus<br />

group is extremely complex with<br />

28 subspecies recognized by Schiøtz,<br />

(1999). Wieczorek et al. (2001) split H.<br />

viridiflavus in<strong>to</strong> 10 species <strong>and</strong> according<br />

<strong>to</strong> this paper <strong>the</strong> subspecies<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arusha National Park should be<br />

included, along with seven more taxa<br />

in Hyperolius gl<strong>and</strong>icolor (Peters,<br />

1878). Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> books published<br />

before Schiøtz (1999) considered <strong>the</strong><br />

omma<strong>to</strong>stictus subspecies as members<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> large group <strong>of</strong> Hyperolius marmoratus.<br />

Christina M. Richards (1981)<br />

discussed <strong>the</strong> pattern variation <strong>of</strong> different<br />

subspecies <strong>of</strong> Hyperolius viridiflavus<br />

including H.v. omma<strong>to</strong>stictus.<br />

Identification<br />

Amedium sized treefrog with a snoutvent<br />

length up <strong>to</strong> 30 mm, <strong>the</strong> shape<br />

resembles somewhat <strong>the</strong> European<br />

treefrog Hyla arborea or <strong>the</strong> American<br />

barking treefrog Hyla gratiosa. Fingers<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>es bear terminal adhesive discs<br />

<strong>and</strong> are webbed. The snout is truncate.<br />

Spotted individual from <strong>the</strong> rest house pond.<br />

34<br />

As in all <strong>the</strong> species <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> genus<br />

Hyperolius,<strong>the</strong> pupil is horizontal <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

tympanum concealed. The colour pattern<br />

<strong>of</strong> H.v. omma<strong>to</strong>stictus is extremely variable<br />

usually <strong>the</strong> dorsum is dark brown<br />

with small white rings or white spots that<br />

can be completely absent in some individuals.<br />

During <strong>the</strong> day frogs seen resting<br />

on <strong>the</strong> vegetation can be almost<br />

white. A few adult males <strong>and</strong> most juveniles<br />

are beige or brown with undulating<br />

dorsolateral stripes. The limbs are <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

red especially on <strong>the</strong> underside. Males<br />

present a large vocal sac on <strong>the</strong> throat<br />

protected by a gular disc.<br />

Geographic Range<br />

The distribution range <strong>of</strong> Hyperolius<br />

viridiflavus complex includes most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />