The view that politics should be kept out of sport would never have cut any ice with Max Mosley, who has died aged 81. As the son of the British Union of Fascists’ leader, Sir Oswald Mosley, he was brought up in a notoriously political household during the 1940s and 50s, and in his 20s was involved in his father’s postwar Union Movement.

After being drawn into motor racing in the early 60s, he demonstrated that sport could be politics continued by other means. He rose to the presidency of the sport’s governing body, the FIA, but while he was admired for his clarity of mind and intellect, he was feared for the ruthlessness with which he would manipulate events to suit himself and crush his opponents.

These qualities came to the fore in 2008 when he found himself embroiled in scandal after the News of the World exposed his involvement in what it described as a “sick Nazi orgy” that featured German sex workers and sado-masochistic sex. He weathered a storm of demands for his resignation as FIA president and successfully sued the newspaper for breach of privacy, despite what the high court judge in the case described as his “reckless and almost self-destructive” behaviour.

He subsequently became involved in a campaign to curb the excesses of tabloid newspapers, and was a prominent supporter of the Hacked Off campaign, which helped bring about the Leveson inquiry into phone hacking.

Mosley had been accustomed to controversy since birth. A few weeks after he was born, in June 1940, as Britain braced itself for a Nazi invasion, his mother, Diana (nee Freeman-Mitford – the third eldest of the six illustrious Mitford sisters), was interned under Defence Regulation 18B, a measure designed to sweep up fascists, fifth columnists and Nazi sympathisers.

Sir Oswald had been detained a month earlier. Aside from their involvement in British fascism, the Mosleys had been married in Joseph Goebbels’ drawing-room in Berlin in 1936, after which their special guest Adolf Hitler had presented the newlyweds with a framed photograph of himself.

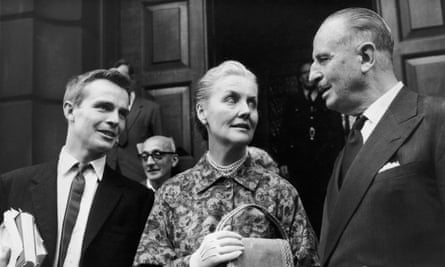

Max and his older brother, Alexander, were separated from their parents until they were released from Holloway prison in November 1943. After the war, the Mosleys spent their time moving around Europe, cruising the Mediterranean on the family yacht or visiting Sir Oswald’s Spanish friend, General Francisco Franco.

They settled in France in 1951, and Max acquired a Eurocentric education in France and Germany before attending Millfield school, Somerset, then went to Christ Church, Oxford. He became secretary of the Oxford Union and graduated in physics in 1961. He went on to study patent and trademark law, and qualified as a barrister in 1964.

His suave exterior masked a highly volatile character, made more so by the knowledge that his family name would exclude him from any involvement in British politics, though otherwise he would surely have thrived in the Westminster jungle. In 1962 he was arrested after a punch-up in Dalston, east London, while protecting his father from a mob as he canvassed for the Union Movement. Max also trained as a paratrooper with the Territorial Army.

While he was still at Oxford, his interest in motor racing was sparked by a visit to the Silverstone circuit in Northamptonshire with his wife, Jean (nee Taylor). The couple had married in 1960 after meeting at a Union Movement party. The sport appealed to the thrill-seeking Max, and he began dabbling in motor racing in his spare time.

He won a dozen races in 1966-67, and in 1968 he formed the London Racing Team to compete in European Formula Two. He was a competitor in the race at Hockenheim in April 1968 in which the Scottish ace Jim Clark was killed, and finished ahead of Graham Hill in the same event.

However, he realised he would never be a top-flight competitor and in 1969 he quit driving to become a co-founder of the March Engineering team with Alan Rees, Graham Coaker and the designer Robin Herd. March enjoyed a spectacular start in the 1970 Formula One season.

As well as running their own drivers, they constructed chassis for the reigning world champion Jackie Stewart and his Tyrrell team, and consequently finished third in the 1970 constructors’ table. However, the team ran into financial problems, and had to borrow £20,000 to remain solvent for 1971. Over the following years they enjoyed considerable success building cars for Formula Two, but Mosley grew weary of the constant struggle to keep afloat and sold his March shareholding in 1977.

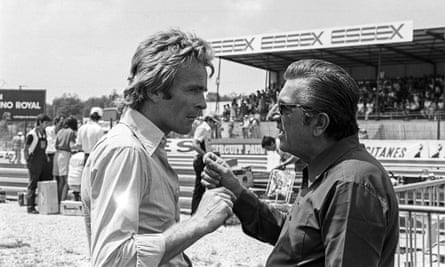

He had struck up a friendship with the ambitious entrepreneur Bernie Ecclestone, who had bought the Brabham Formula One team and was developing a vision of how the then-chaotic sport should develop. The pair became the prime motivators behind the Formula One Constructors’ Association (Foca), formed in 1974 to represent the interests of the racing teams in negotiations with the governing body, the Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile (Fisa), the motor sport subsidiary of the overarching FIA. Spotting Mosley’s political and legal skills, Ecclestone made him Foca’s legal adviser.

The early 80s brought Formula One’s so-called Fisa-Foca war, a power struggle for the sport’s TV and commercial rights which pitted Mosley and Ecclestone against Jean-Marie Balestre, Fisa’s autocratic French president. After much acrimony and a threat by the teams to form their own breakaway championship, the dispute was settled by both parties signing the Concorde agreement, a document masterminded by Mosley. In essence, the teams agreed to participate in all rounds of the FIA’s new championship in exchange for a larger share of the financial spoils. The agreement continued to underpin the structure of Formula One for the next 40 years.

It became widely believed that Ecclestone and Mosley were a wily double act, carving up Formula One between them behind closed doors. The fact that the Concorde agreement in effect gave Ecclestone carte blanche to exploit Formula One’s commercial rights lent credence to this view, but both protagonists always denied it.

“People always think of us two together, and I like to think of Bernie as being a close friend,” Mosley commented. “We haven’t agreed about everything by any means. I’ve never worked for Bernie and I’m not in any sense under his influence.”

In 1991, he sought to extend his power by challenging Balestre for the presidency of Fisa, arguing that the organisation’s structure was chaotic and that Balestre had too much on his plate to function effectively. His sleek political skills guaranteed a comfortable victory. With Ecclestone already installed as FIA vice-president, the former Foca rebels had now taken control of the engine room of the motor sport establishment.

Mosley tightened his grip further in 1993 by becoming president of the FIA, with Fisa being absorbed back into the parent organisation. He was thus in charge of overseeing all worldwide motor sport as well as general motoring issues such as road safety and environmental impact.

In the early 80s, Mosley made an unsuccessful attempt to launch himself into British politics as a Conservative candidate. However, as president of the FIA, he was still able to exercise wide-ranging political influence, since the organisation has consultative status at the European parliament, the UN and other international bodies. In the late 90s he became a donor to the Labour party and supported Tony Blair’s government. In 2018, the Labour party declared it would not accept further donations from Mosley following revelations about a racist leaflet he had published in 1961.

Following the death of the triple world champion Ayrton Senna and the Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger on a grim weekend at Imola, Italy, in 1994, Mosley embarked on a campaign to improve safety in Formula One, including limited engine sizes and improved crash-testing standards.

“In the first Formula Two race I ever did, there were I think 21 cars on the grid in April,” Mosley said in 2004. “By July three of the drivers were dead. It was like being in a frontline regiment in Vietnam or something. I remember thinking: ‘If ever I get to any position of power in motor racing I’ll do something about this,’ because the attitude in those days was: ‘Well, if you don’t like it, don’t take the risk.’”

Mosley was also quick to sense the rising tide of environmentalism, and saw that Formula One’s reputation as a wasteful rich man’s club risked drawing fire from politicians and eco-activists.

He embarked on a mission to reduce the sport’s exorbitant costs by standardising components and to enhance its usefulness by developing technologies with applications beyond the racetrack. For instance, he backed research into the kinetic energy recovery system, a method of capturing and reusing a vehicle’s kinetic energy. In 2006 he was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by the French government for his work in road safety and motor sport.

The issue of tobacco sponsorship in Formula One naturally fell within his purview, and in 1997 he battled to delay the EU’s proposed ban on tobacco advertising to give Formula One time to find new sources of funding. He was nimble enough to accomplish this without provoking the kind of furore that surrounded Ecclestone’s £1m donation to the Labour party, which was widely criticised as a bid to pre-empt the tobacco ban in the UK.

Mosley’s robust helmsmanship brought discipline and purpose to the FIA, but his condescending and supercilious manner guaranteed that he would make enemies along the way. His pronouncements on how Formula One should be run often brought him into conflict with team bosses, especially McLaren’s Ron Dennis, who the motor sport writer Alan Henry felt was regarded by Mosley as “almost an irritating NCO who has been promoted beyond his status”.

Patrick Head, the co-founder of the Williams team, complained about “the patronising way the FIA, and Max particularly, deals with the teams. He has changed technical regulations at enormous cost and with late notice. You can see from his own public announcements that he hates all the team principals. He detests them.”

Yet Mosley was repeatedly able to win re-election to the FIA presidency, thanks not least to his skill in cultivating support among the worldwide network of automobile clubs which comprise the FIA’s membership. The value of this was dramatically emphasised in 2008, in the aftermath of the exposé of his sexual predilections in the News of the World. The newspaper had secretly filmed him engaged in sado-masochistic sex with sex workers in a London flat, and the participants’ outfits prompted the tabloid to describe the proceedings as “a depraved Nazi-style orgy in a torture dungeon”. The allegations seemed fatally damaging.

Mosley’s presidential tenure appeared doomed as motor manufacturers including Mercedes, BMW, Honda and Toyota expressed their disgust, the ex-racing champions Stewart and Jody Scheckter called for his head, and even Ecclestone suggested that his old comrade’s days were numbered. However, it was a measure of Mosley’s baleful influence that most drivers and racing team personnel kept their opinions to themselves. An unabashed Mosley then summoned every ounce of patrician hauteur and faced down his critics, striking a crucial blow by comfortably winning a confidence vote at a specially convened FIA meeting.

Then he successfully sued the News of the World for invasion of privacy, claiming that he had indulged in “a perfectly harmless activity” with no Nazi connotations whatsoever. He was awarded £60,000 damages and £450,000 in legal costs. However, this was not enough for him. He was an early supporter – though not a financial backer – of the Hacked Off pressure group, which helped persuade the then prime minister, David Cameron, to set up the Leveson inquiry “into the culture, practices and ethics of the press” in 2011, and he underwrote the court costs of claimants who believed they had had their phones hacked by the News of the World. In July 2011 Rupert Murdoch closed the News of the World.

Remarkable as Mosley’s fightback had been, the affair was also fascinating for the light it shed on Formula One’s secret alliances and vendettas. Many commentators wondered whether the newspaper exposé was in some way connected to the $100m fine meted out by the FIA to the McLaren team in 2007, after McLaren were deemed guilty of appropriating technical secrets from Ferrari in the so-called “spygate” scandal. As ever, conclusive proof was nowhere to be found.

Mosley will be remembered as a brilliant but flawed figure who, with Ecclestone, was pivotal in transforming Formula One into a global spectacle. As FIA president, he proved himself an innovative thinker who pushed through safety measures and technological advances in motor sport and in the wider world of motoring. Yet there was always a sense that everything he did was only a substitute for the mainstream political career that had been denied him.

He is survived by Jean and their son Patrick. Another son, Alexander, predeceased him.

Max Rufus Mosley, motor racing executive, born 13 April 1940; died 23 May 2021