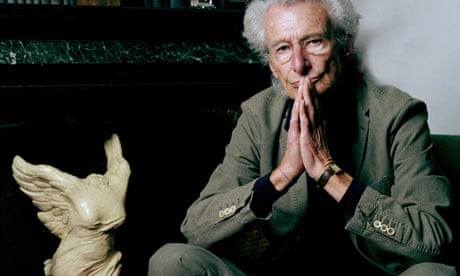

The writer Harry Mulisch, who has died of cancer aged 83, was unsurpassed in 20th-century Dutch literature but missed out on the international recognition that writing in a more widely read language would surely have brought him. He was far from alone in his belief that he should have been awarded the Nobel prize for literature.

Modesty was not one of his qualities and Mulisch made no secret of the fact that he was highly intelligent and an exceptional and versatile writer, his arrogance leavened by a strong sense of humour and occasional self-deprecation. One of his most famous remarks was that he was the second world war – in person. The conflict was the most important event in his life and the driving force behind much of his writing.

The son of Karl Mulisch, an Austrian banker who fled to the Netherlands after the first world war, and a Jewish mother, Alice Schwarz, Harry lived through the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands as a teenager in the town of Haarlem, where he was born. Most of his later life was spent in Amsterdam, where he had a canalside mansion, typically Dutch in looking modest on the outside but lavishly appointed inside.

Mulisch Sr collaborated with the occupiers, running a formerly Jewish bank to collect the assets of Dutch Jews deported to the death camps. As the son of a Jewish woman, Harry himself was a candidate for deportation, and was forced to leave school early in 1944, but his father used his influence not only to save his son but also to secure the release from a concentration camp of Alice. Her other relatives died in the Holocaust. The couple had divorced before the war and she left for America in 1945. Karl was sentenced to three years' imprisonment by the Dutch after the war for collaboration.

Harry had hoped to make a career as a scientist, but was driven to earn his living as a writer. His background, with its moral complexities – including the bitter irony of owing his life to a traitor father – equipped Mulisch to tackle head-on the profound Dutch national trauma caused by the German invasion. The Netherlands had declared itself neutral before the war, as in 1914. The Dutch in general were no prewar admirers of Hitler, but were usually favourably disposed to their German neighbours, to whom many were directly related and with whom they did the bulk of their trade. Thus the invasion in May 1940 was not just an act of war, but a colossal betrayal that generated a hostility that lasted for many decades after 1945 and was unmatched in any other country attacked by the Nazis.

Such is the context of Mulisch's most famous novel, De Aanslag (1982; translated into English as The Assault, 1985). A Dutch pro-Nazi police chief is assassinated by the resistance and his body dumped on the doorstep of an innocent family. The occupiers respond with indiscriminate reprisals against civilians, including the parents of a boy called Anton, who survives to evaluate these events as a mature man.

A first-class thriller, the book also examines how the occupation is often redacted in Dutch memories. Just one moral question among many it raises is how the resistance justified murdering a Nazi lackey, an act with no effect on the war, while knowing in advance that the Germans would shoot civilians in revenge. The Assault was translated into 32 languages and the Dutch film of the book won the Oscar for best foreign film in 1987. It is a standard school text.

If The Assault is his best-known work, De Ontdekking van de Hemel (The Discovery of Heaven, 1992; also filmed) is widely held to be his best. Not the easiest of reads, it was chosen as the best book ever written in Dutch in a nationwide poll in 2007. The central story is a friendship between two intellectual male friends in a love-triangle with a female musician, who gives birth to a boy who turns out to be a messenger from God. The book is a pyrotechnic display of fine writing, human drama, intellectual debate and profound knowledge of science and history, with dashes of mysticism and fantasy.

Mulisch produced 13 novels and at least 20 other books – essays, plays, opera librettos, poetry, short stories and reportage, including an outstanding account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the supreme bureaucrat of the Holocaust, executed by the Israelis in 1962. His last novel, Siegfried, returned to the second world war and features a successful writer of world renown, while postulating a love-child of Hitler and Eva Braun. It was published in English in 2003.

He won the Anne Frank prize in 1957, an honorary doctorate from Amsterdam University, the Prize of Netherlands Letters (a lifetime achievement award in 1995) and was decorated by the Dutch, French and German governments. British response to his work was less enthusiastic, with critics suggesting that Mulisch may have suffered in translation.

Mulisch married Sjoerdje Woudenberg in 1971. They had two daughters. The couple never divorced and remained friends even after Mulisch began a relationship in 1992 with Kitty Saal, with whom he had a son. All five survive him.