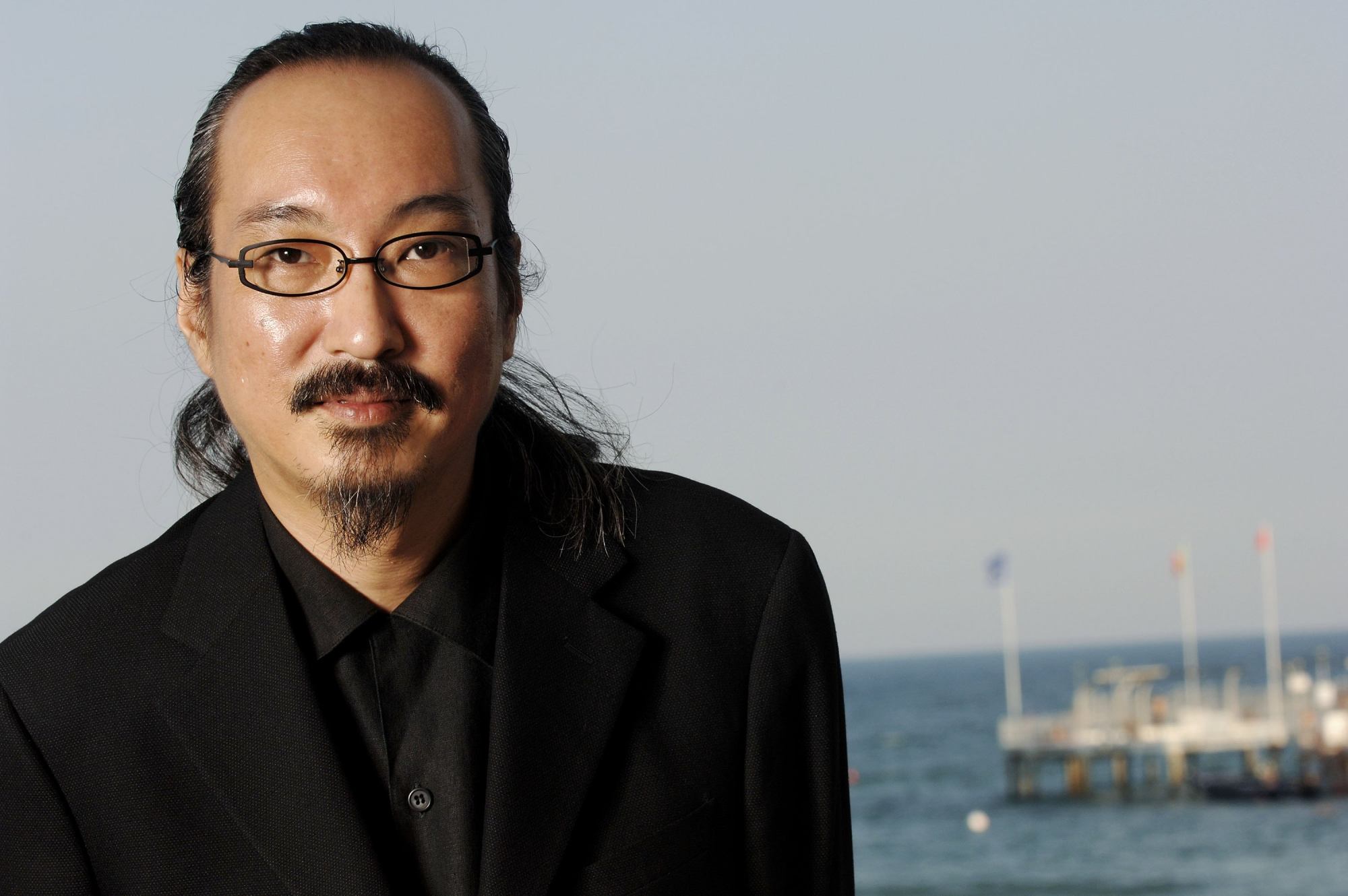

Explainer | Who was Satoshi Kon, Japanese animation director of Perfect Blue and Paprika who influenced filmmakers including Darren Aronofsky?

- Satoshi Kon may have directed only four feature films, but his influence on other filmmakers, among them Darren Aronofsky, is unmistakable

- As a young man, he helped artist Katsuhiro Otomo serialise his sci-fi classic Akira, and his own later works influenced Aronofsky’s Black Swan

Satoshi Kon directed just four feature films before his untimely death in 2010 at the age of 46, yet he is widely regarded as one of the most influential animators of his generation.

Born and raised in Sapporo, the largest city on Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, Kon chose his vocation at a very young age.

After high school, he enrolled in Musashino Art University, where he studied graphic design. During this time he drew his first manga, which was recognised by influential publishing house Kodansha in its annual Tetsuya Chiba awards.

Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist – celebration of an amazing talent

He was offered his first job as a manga artist at Kodansha’s lead publication, Young Magazine, in which Katsuhiro Otomo’s seminal science-fiction classic Akira was being serialised.

Thrown together with one of the form’s leading creative forces, Kon subsequently worked with Otomo on a number of projects, including his live-action feature film World Apartment Horror (1991) and, most notably, as scriptwriter and background artist for “Magnetic Rose”, one segment of the animated sci-fi anthology film Memories (1995).

Drawing inspiration from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Ridley Scott’s Alien, the story follows the crew of a deep-space salvage freighter, who answer a distress call from an abandoned space station only to be bombarded by hallucinations relating to their own memories once on board.

It would be the first time that Kon would explore fluctuating perspectives and characters who wrestle with their grasp on reality – themes that would resurface time and again throughout his work.

These experiences led to a number of collaborations with Mamoru Oshii, another giant of the medium, including co-writing the manga series Seraphim 266613336Wings. Conceived to emulate the success of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, this proved a less fruitful experience.

Kon and Oshii clashed over the creative direction of the post-apocalyptic series, and the project was abandoned prematurely in 1995. Oshii grew frustrated with the shy and deferential Kon, who was known to become stubborn and nasty if he felt his artistic vision was being compromised.

Following these unsatisfying experiences, Kon vowed to focus his efforts solely on anime projects where he could retain full creative control. That moment materialised when he was invited by producer Masao Maruyama of Madhouse Studios to direct his first animated feature film.

After Nezha and Chang An, is Chinese animation ready to take on the world?

In the West, Kon also found inspiration in the films of Terry Gilliam, particularly his time-travelling fantasy Time Bandits and Orwellian thriller Brazil, and the writing of science fiction author Philip K. Dick.

Similarly, many Hollywood filmmakers have revealed that Kon influenced their films. Darren Aronofsky has been a vocal fan, and echoes of Perfect Blue are clearly visible in both Requiem for a Dream and Black Swan.

Kon’s final film, Paprika, addresses many of the same themes and dream-weaving concepts as featured in Christopher Nolan’s 2010 blockbuster Inception.

At the time of his death, Kon was deep in development on his next feature, Dreaming Machine. Producer and friend Masao Maruyama had vowed to complete the film, but after acknowledging that Kon’s original vision would be lost in the hands of another filmmaker, it remains far from completion.

Where to begin: Perfect Blue (1997)

Kon’s electrifying debut is the perfect entry point for the uninitiated, as it lays out the blueprint for what would become his signature style and storytelling approach.

Almost all of Kon’s output focuses on a female protagonist. In Perfect Blue, his heroine is Mima, a former pop idol who has decided to quit her girl group to pursue a career in acting.

It is a decision that upsets many of her passionate followers, and attracts the unwanted attention of a stalker who calls himself Me-Mania, and chronicles her every waking moment in terrifying detail on a website known as Mima’s Room.

Mima’s change of artistic vocation, paired with the growing realisation that she may be in danger, sees the young starlet spiral into hysteria that is fuelled by paranoia and further exacerbated by the challenging nature of her first acting role.

Kon dives headlong into the realm of psychological horror – largely uncharted waters for anime at that time – and his debut is a dizzying, disorienting nightmare of fractured personalities and mental instability that skewers celebrity culture and the exploitative nature of the media as readily as it shocks with its genuinely chilling imagery.

The masterpiece: Millennium Actress (2001)

Within his limited oeuvre, Kon can take solace in the fact that he never directed anything close to a bad film, and any one of his four completed features – the others being Tokyo Godfathers (2003) and Paprika (2006) – can legitimately be hailed as representing his finest hour.

His second feature, Millennium Actress, is at once a reverent celebration of the Japanese film industry’s golden studio era, a whistle-stop history lesson that traverses five decades of post-war evolution in under 90 minutes, and a visually and structurally audacious odyssey through the fading memory of an ageing, heartbroken performer.

The story sees documentarian Genya Tchibana go in search of Chiyoko Fujiwara, a legendary screen actress who has since retired and become a recluse – inspired by Setsuko Hara, favourite of Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu.

They worked together at a once-prestigious film studio which has since gone out of business. Genya presents Chiyoko with a key that was once hers, which he has kept for her for many years. This triggers a whirlwind of memories for the elderly actress as she recalls a lifetime spent in the movies, and pining for the young dissident who entrusted the key to her as a young girl.

Kon’s film fabulously intertwines Chiyoko’s memories with her career in cinema, blurring the lines between her life and the characters she embodied in everything from samurai epics to sci-fi spectacles.

What unfolds is a beautiful acknowledgement that life does not begin and end with one’s actions, but also includes all the stories, both real and imagined, that we experience throughout our lifetimes.

The hidden gem: Paranoia Agent (2004)

Kon’s only anime series is this endlessly inventive 13-episode detective story, which begins as an investigation into a series of disturbing assaults by a young attacker who wields a baseball bat.

Much like David Lynch’s genre-defying Twin Peaks, however, the crime is merely a jumping off point for Kon’s exploration of the lives of the many people who unwittingly come into contact with the violent young man.

Police officers, schoolchildren, gangsters, call girls, and the staff at an animation studio are just a few of the lonely souls whose world is turned upside down, but under Kon’s meticulous direction all become compelling protagonists in his unflinching depiction of urban malaise.