DNA Reveals How Darwin's Finches Evolved

A study finds that a gene that helps form human faces also shapes the beaks of the famously varied Galápagos finches.

Wide, slender, pointed, blunt: The many flavors of beak sported by the finches that flit about the remote Galápagos Islands were an important clue to Darwin that species might change their traits over time, adapting to new environments.

Now scientists peering into the DNA of these birds have found a piece of genetic code that contributes to the striking variation in beak shape. (Watch a video to learn more about the unique animals of the Galápagos.)

The discovery is described in a study published today in the journal Nature that also brings fresh insights into the forces that drive the formation of new species. The birds' past—and their current connections to one another—is more tangled than previously thought.

The Galápagos finches are ideal subjects for observing the drama of evolution. The islands kept them isolated from competition with other birds on the South American mainland, and each island became its own little world. As a result, the 14 species show a startling range of beak shapes. Each is finely tuned to a specific way of getting food.

To actually see evolution take place, starting in 1973 Rosemary and Peter Grant began spending months each year on the tiny volcanic outcrop called Daphne Major, meticulously measuring changes in the shapes and sizes of the finches there in tandem with variations in food supply and climate. The married scientific team are among the authors of the new paper. (Learn more about the Grants.)

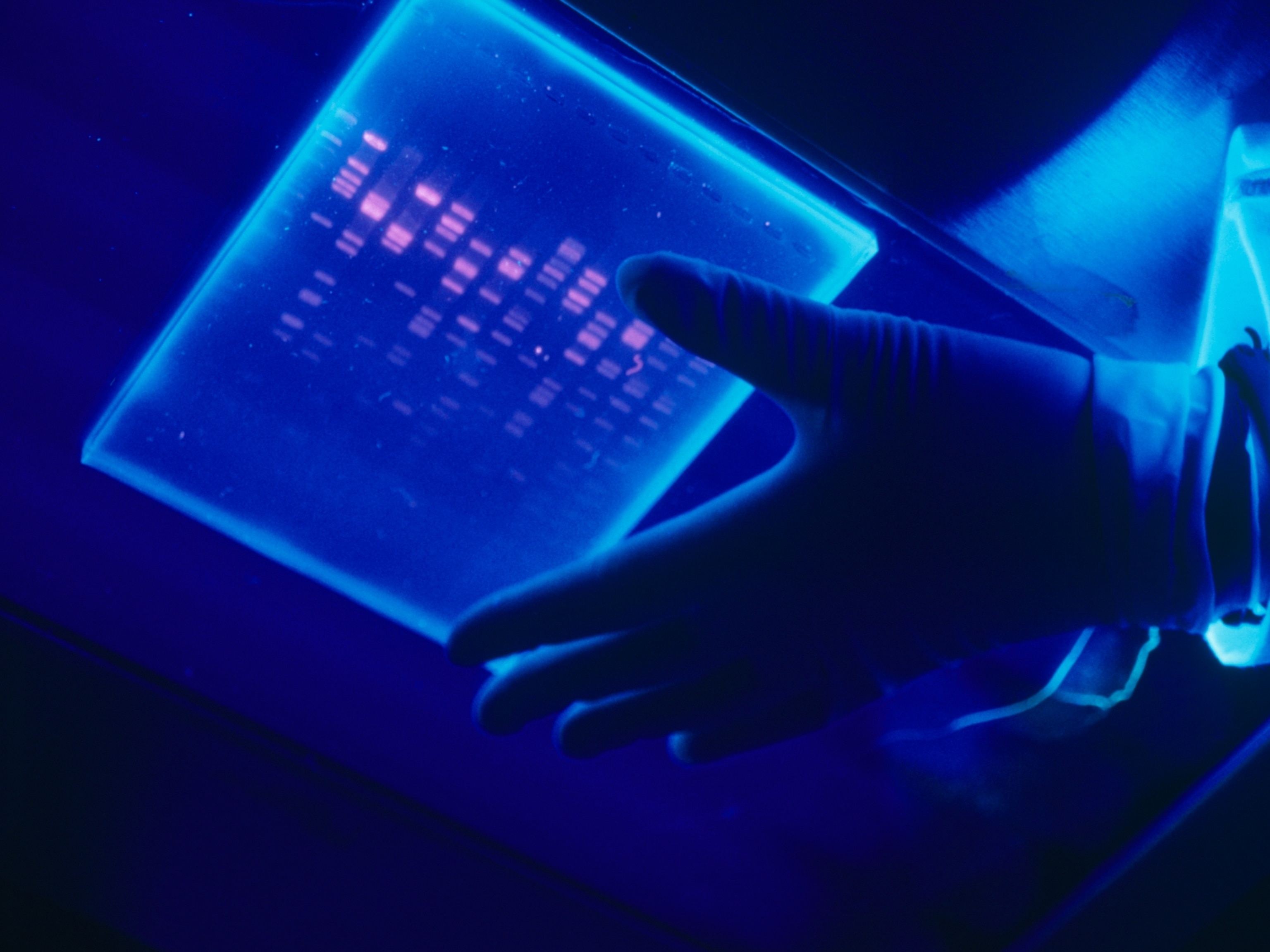

In the new article, scientists for the first time sequenced the genomes of the finches. They looked at 120 individuals, drawing from all of the known species.

By comparing the genomes, they found a handful of subtle variations that appear connected to beak shape. The most obvious is in a gene known as ALX1, which is critical to the formation of facial and head bones. In humans, the malfunctioning of this gene results in deformities such as cleft palates. In the finches, a tiny difference in the ALX1 gene distinguished between birds that use a blunt, stout beak to crack open tough seed casings, and other birds whose more pointy beaks are better equipped to pick little seeds off the ground.

Among the ground finches (Geospiza fortis) of Daphne Major, birds that inherited the blunt version of the gene from both parents had the bluntest beaks, those with one blunt and one pointy version of the gene had intermediate beaks, and those with two pointy variants had the sharpest.

"I'm convinced that these are one of the changes that is explaining the difference between blunt and pointed [beaks]," said Leif Andersson, a geneticist at Sweden's Uppsala University, and one of the paper's authors.

William Provine, a professor at New York's Cornell University and an expert in the history of evolutionary science, cautioned that the picture of which genes are controlling beak shape might not be as clear as this paper suggests. If more finch genomes are deciphered, the results could add new twists. "You don't know what else affects beak shape," Provine said.

Andersson said they are now working to expand the collection of finch genomes, in hopes it will further clarify the genes driving differences between the birds.

Galápagos mockingbirds (upper right) first gave Darwin the idea that island species might vary. Back in England, he examined the finches (three species on upper left; bottom left is a yellow warbler) more closely and realized their significance.

Origins of New Species

Additionally, the researchers discovered the species categories weren't as neat as they appeared. One species was made up of three distinct genetic groups, and the genomes of others are more similar than the team expected, suggesting that the birds interbred much more than we had realized, and over a longer time period, say the Grants.

"The most important take-home message may be that species are not fixed, shut off from other species by inability to interbreed. On the contrary, for a long time, millions of years in some cases, they are capable of exchanging genes," the Grants wrote in an e-mail.

The ground finches on Daphne Major illustrate why this can matter to the survival of a species. There, the G. fortis finches have interbred with two other species that tend to have pointy beaks, adding more of the pointy-beak variants into the gene pool. When a devastating drought hit the island in the mid-1980s, the Grants watched as the G. fortis population veered toward a pointier beak better suited to the remaining food supply.

This new discovery—that interbreeding plays a bigger role in evolution than previously thought—echoes the first scientific encounter with these birds, said Frank Sulloway, a historian of science who has written extensively about Darwin. When Darwin first set foot on the Galápagos in 1835, the birds varied so much he failed to realize they were all finches. Another scientist pointed it out when he returned to England.

"In a sense he was fooled by the extraordinary complexity and diversity," Sulloway said. "What this most recent study shows is this process of unfooling ourselves is still going on."

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?