Caves of Faith

In a Silk Road oasis, thousands of Buddhas enthrall scholars and tourists alike.

The human skeletons were piled up like signposts in the sand. For Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk traveling the Silk Road in A.D. 629, the bleached-out bones were reminders of the dangers that stalked the world's most vital thoroughfare for commerce, conquest, and ideas. Swirling sandstorms in the desert beyond the western edge of the Chinese Empire had left the monk disoriented and on the verge of collapse. Rising heat played tricks on his eyes, torturing him with visions of menacing armies on distant dunes. More terrifying still were the sword-wielding bandits who preyed on caravans and their cargo—silk, tea, and ceramics heading west to the courts of Persia and the Mediterranean, and gold, gems, and horses moving east to the Tang dynasty capital of Changan, among the largest cities in the world.

What kept Xuanzang going, he wrote in his famous account of the journey, was another precious item carried along the Silk Road: Buddhism itself. Other religions surged along this same route—Manichaeism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and later, Islam—but none influenced China so deeply as Buddhism, whose migration from India began sometime in the first three centuries A.D. The Buddhist texts Xuanzang carted back from India and spent the next two decades studying and translating would serve as the foundation of Chinese Buddhism and fuel the religion's expansion.

Near the end of his 16-year journey, the monk stopped in Dunhuang, a thriving Silk Road oasis where crosscurrents of people and cultures were giving rise to one of the great marvels of the Buddhist world, the Mogao caves.

Emerging from the wind-sculptured dunes some 12 miles southeast of Dunhuang is an arc of cliffs that drop more than a hundred feet to a riverbed lined with poplar trees. By the mid-seventh century, the mile-long rock face was honeycombed with hundreds of grottoes. It was here that pilgrims came to pray for safe passage across the dreaded Taklimakan Desert—or in Xuanzang's case, to give thanks for a successful journey.

Within the caves, the monochrome lifelessness of the desert gave way to an exuberance of color and movement. Thousands of Buddhas in every hue radiated across the grotto walls, their robes glinting with imported gold. Apsaras (heavenly nymphs) and celestial musicians floated across the ceilings in gauzy blue gowns of lapis lazuli, almost too delicate to have been painted by human hands. Alongside the airy depictions of nirvana were earthier details familiar to any Silk Road traveler: Central Asian merchants with long noses and floppy hats, wizened Indian monks in white robes, Chinese peasants working the land. In the oldest dated cave, from A.D. 538, Xuanzang would even have seen those bandits again—only in this rendition, the thugs had been captured, blinded, and ultimately converted to Buddhism.

When Xuanzang passed through Dunhuang, he could not have known that his translations of the Buddhist sutras would inspire Mogao's artists for centuries to come. Nor could he have known that more than 1,200 years later his work would lead to the rediscovery and plunder, and ultimately the protection, of the grottoes. All the monk could see was that here, in a desert on the outskirts of the empire, the Buddhist faith was already being transformed with each stroke of paint in the darkness.

For a religion that preaches the transience of all things, the ever shifting sands of China's western deserts might seem the perfect setting for such glorious artistic expression. But the miracle of the Mogao caves is not their impermanence but rather their improbable longevity.

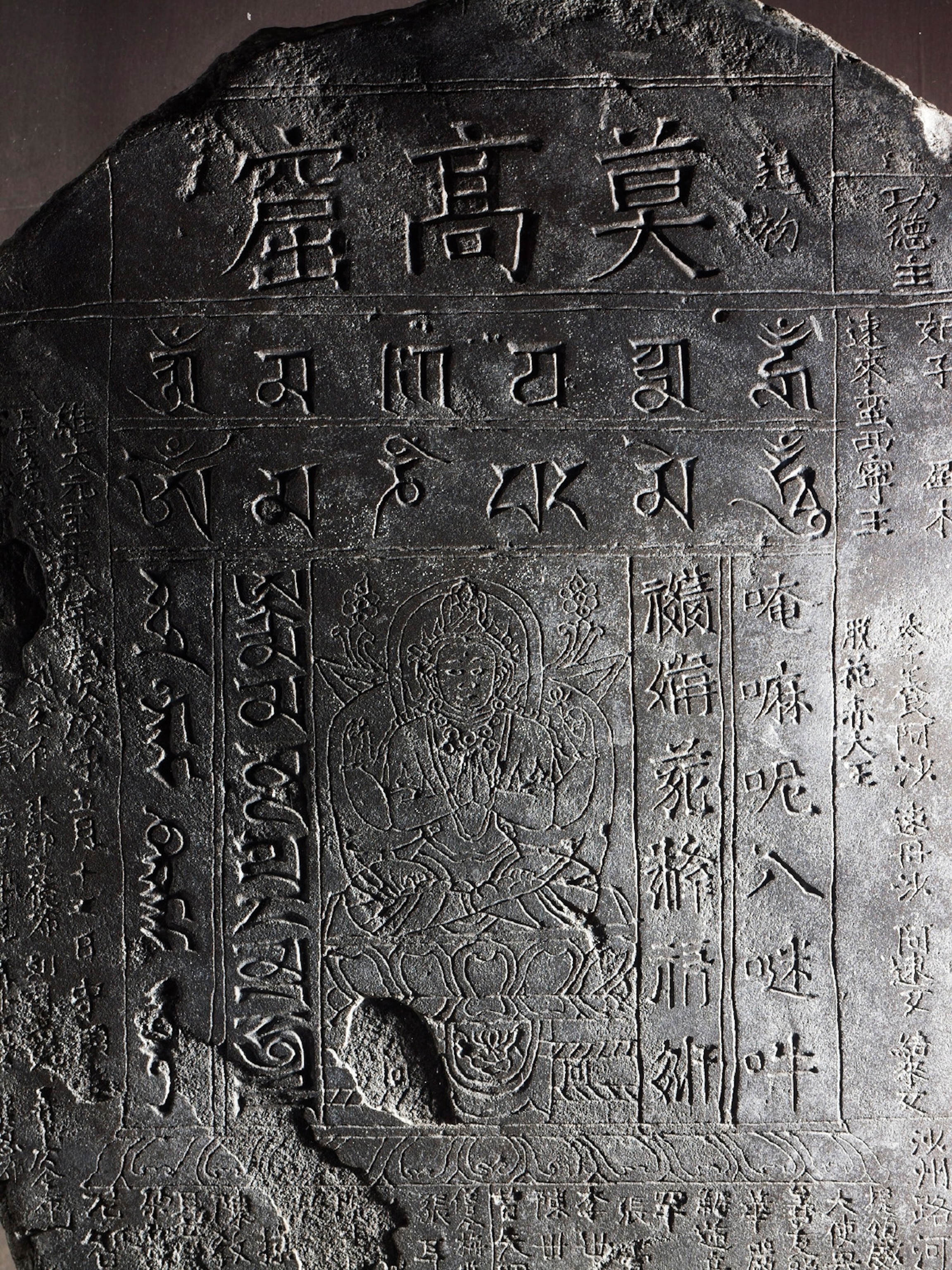

Carved out between the fourth and 14th centuries, the grottoes, with their paper-thin skin of painted brilliance, have survived the ravages of war and pillage, nature and neglect. Half buried in sand for centuries, this isolated sliver of conglomerate rock is now recognized as one of the greatest repositories of Buddhist art in the world. The caves, however, are more than a monument to faith. Their murals, sculptures, and scrolls also offer an unparalleled glimpse into the multicultural society that thrived for a thousand years along the once mighty corridor between East and West.

The Chinese call them Mogaoku, or "peerless caves." But no name can fully capture their beauty or immensity. Of the almost 800 caves chiseled into the cliff face, 492 are decorated with exquisite murals that cover nearly half a million square feet of wall space, some 40 times the expanse of the Sistine Chapel. The cave interiors are also adorned with more than 2,000 sculptures, some of them among the finest of their era. Until just over a century ago, when a succession of treasure hunters arrived across the desert, one long-hidden chamber contained tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts.

Whether taking the longer northern route or the more arduous southern passage, travelers converged on Dunhuang. Caravans came loaded with exotic goods redolent of distant lands. Their most important commodities, however, were ideas—artistic and religious. It's no wonder that the Mogao painters, illustrating the greatest of all Silk Road imports, infused their murals with an array of foreign elements, from pigments to metaphysics.

"The caves are a time capsule of the Silk Road," says Fan Jinshi, director of the Dunhuang Academy, which oversees research, conservation, and tourism at the site. A sprightly 71-year-old archaeologist, Fan has worked at the grottoes for 47 years, ever since she arrived in 1963 as a fresh graduate of Peking University. Most other Silk Road sites, Fan says, were devoured by the desert or destroyed by successive empires. But the Mogao caves endured largely intact, their kaleidoscope of murals capturing the early encounters of East and West. "The historical significance of Mogao cannot be exaggerated," Fan says. "Because of its geographical location at a transit point on the Silk Road, you can see the mingling of Chinese and foreign elements on nearly every grotto wall."

Today East and West are converging again on Dunhuang, this time to help save the grottoes from what may be the biggest threat in their 1,600-year history. Mogao's murals have always been fragile, the thinnest tissue of paint caught in a corrosive battle between rock and air. Over the past few years, they have faced the combined assault of natural forces and a surge of tourists. In an effort both to conserve the Silk Road masterpieces and to contain the tourists' impact, Fan has enlisted the help of teams of experts from across Asia, Europe, and the United States. It is a cultural collaboration that echoes the glorious history of the caves—and may help ensure their survival.

The caves began as a vision of light. One evening in A.D. 366, a wandering monk named Yuezun saw a thousand golden Buddhas blazing in a cliff. Inspired, he chiseled a small meditation cell into the rock; others quickly followed. The first caves were no larger than coffins. Soon, monastic communities began carving out larger caverns for public acts of devotion, adorning the shrines with images of the Buddha. It is these early grottoes that inspired the nickname the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.

Their canvases consisted of nothing more than river mud mixed with straw, but Dunhuang's artists would, over the centuries, record on these humble surfaces the evolution of Chinese art—and the transformation of Buddhism into a Chinese faith.

One of Mogao's creative peaks came during the seventh and eighth centuries, when China projected both openness and power. The Silk Road was booming, Buddhism was flourishing, and Dunhuang was paying fealty to the Chinese capital. The Tang cave painters displayed a fully confident Chinese style, covering whole walls with minutely detailed Buddhist narratives whose color, movement, and naturalism made the imaginative landscape come alive. The Middle Kingdom would later turn inward, finally shutting itself off from the world during the Ming dynasty in the 14th century.

"Unlike Indian Buddhists, the Chinese wanted to know in detail all the forms of the afterlife," says Zhao Shengliang, an art historian at the Dunhuang Academy. "The purpose of all this color and movement was to show pilgrims the beauty of the Pure Land—and to convince them that it was real. The painters made it feel like the whole universe was moving."

More earthly tumult periodically swept through Dunhuang. Yet even as the town was conquered by competing dynasties, local aristocracies, and foreign powers—Tibet ruled here from 781 to 847—the creative enterprise at Mogao continued without pause. What accounts for its persistence? It may have been more than a simple respect for beauty or Buddhism. Rather than wiping out all traces of their predecessors, successive rulers financed new caves, each more magnificent than the last—and emblazoned them with their own pious images. The rows of wealthy patrons depicted on the bases of most murals increased in size over the centuries until they dwarfed the religious figures in the paintings. The showiest patron of all may have been Empress Wu Zetian, whose desire for divine projection—and protection—led her to oversee, in 695, the creation of the complex's largest statue, a 116-foot-tall seated Buddha.

By the late tenth century the Silk Road had begun to fade. More caves would be dug and decorated, including one with sexually charged tantric murals that was built in 1267 under the Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan. But as new sea routes opened and faster ships were built, land caravans slipped into obsolescence. China, moreover, lost control over large portions of the Silk Road, and Islam had started its long migration over the mountains from Central Asia. By the early 11th century several of the so-called western regions (part of modern-day Xinjiang, in China's far west) had been converted to Islam, and Buddhist monks placed tens of thousands of manuscripts and paintings in a small side chamber adjoining a larger Mogao grotto.

Were the monks hiding documents for fear of an eventual Muslim invasion? Nobody knows for sure. The only certainty is that the chamber—now known as Cave 17, or the Library Cave—was sealed up, plastered over,and concealed by murals. The secret cache would remain entombed for 900 years.

The diagonal scar gouged by an ancient sand drift is still visible on the murals outside Cave 17. By the turn of the 20th century, when a Taoist priest named Wang Yuanlu became the sanctuaries' self-appointed guardian, many of the abandoned grottoes were buried in sand. In June 1900, as workers cleared away a dune, Wang found a hidden door that led to a small cave crammed with thousands of scrolls. He gave some of them to local officials, hoping to elicit a donation. All he received was an order to seal up the contents of the cave.

It would take another encounter with the West to reveal the secrets of the caves—and to sound China's patriotic alarms. Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-born scholar working for the British government in India and the British Museum, made it to Dunhuang in early 1907 using Xuanzang's seventh-century descriptions to guide him across the Taklimakan Desert. Wang refused to let the foreigner see the bundles from the Library Cave—until he heard that Stein too was a keen admirer of Xuanzang. Many of the manuscripts, it turned out, were Xuanzang's translations of the Buddhist sutras that he had brought from India.

After days of wheedling Wang and nights of removing scrolls from the cave, Stein left Dunhuang with 24 cases of manuscripts and five more filled with paintings and relics. It was one of the richest hauls in the history of archaeology—all acquired for a donation of just 130 pounds sterling. For his efforts, Stein would be knighted in England, and for-ever vilified in China.

Stein's cache revealed a multicultural world more vibrant than anyone had imagined. Nearly a dozen languages appeared in the texts, including Sanskrit, Turkic, Tibetan, and even Judeo-Persian, along with Chinese. The used paper on which many sutras had been copied offered startling glimpses into daily life along the Silk Road: a contract for trading slaves, a report on child kidnapping, even a Miss Manners-style apology for drunken behavior. One of the most precious objects was the Diamond Sutra, a 16-foot-long scroll that had been printed from woodblocks in 868, nearly six centuries before Gutenberg's Bible.

Others—French, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese—quickly followed in Stein's path. Then in 1924 came American art historian Langdon Warner, an adventurer who might have served as inspiration for the fictional Indiana Jones. Enthralled by the beauty of the caves—"There was nothing to do but to gasp," he later wrote—Warner nevertheless contributed to their destruction, hacking out a dozen mural fragments and removing an exquisite Tang-era sculpture of a kneeling bodhisattva from Cave 328. The art is still in the careful custody of the Harvard Art Museum. But the defaced murals—and the empty space where the sculpture once knelt—are heartrending all the same.

Some Chinese officials, echoing their counterparts in Egypt and Greece, have called for the Mogao artifacts to be returned. Even the Dunhuang Academy's otherwise dispassionate book on the grottoes has a chapter titled "The Despicable Treasure Hunters." Foreign curators, meanwhile, contend that their museums have saved treasures that might otherwise have been lost forever—destroyed in the wars and revolutions of 20th-century China.

Whatever one's views on the issue, there is an inescapable fact: The scattering of Mogao artifacts to museums on three continents has given rise to a new field of study, Dunhuangology, and today scholars around the world are working to preserve the treasures of the Silk Road.

Fan Jinshi didn't set out to be the guardian of the caves. Back in 1963, when she reported to the Dunhuang Academy, the 23-year-old Shanghai native never imagined she would last a year in the forsaken outpost, much less a lifetime. The Mogao caves were impressive, to be sure, but Fan couldn't bear the food, the lack of running water, or the fact that everything—houses, beds, chairs—seemed to be made out of mud.

Then came the Cultural Revolution in 1966, when Chairman Mao's regime laid waste to Buddhist temples, cultural artifacts, and foreign emblems across China. The Mogao caves were a natural target. Fan's group didn't avoid the ferment; the staff of 48 split into about a dozen revolutionary factions, then spent their days condemning and interrogating each other. But for all the bitter infighting, the factions agreed on one principle: The Mogao caves should not be touched. Says Fan, "We nailed shut all the gates to the grottoes."

Nearly half a century later, Fan is leading a very different sort of cultural revolution. As afternoon sunlight streams into her office at the Dunhuang Academy, the director—a diminutive woman with short salt-and-pepper hair—gestures out the window toward the dun-colored cliff face. "The caves have almost every ailment," she says, rattling off the damage caused by sand, water, soot from fires, salt, insects, sunlight—and tourists. Fan oversees a staff of 500, but she recognized as far back as the 1980s that the academy could use the help of foreign conservationists. This may sound simple, but collaborating with foreigners is a sensitive issue at Chinese cultural heritage sites—and the plunder of the Mogao caves a century ago serves as a powerful cautionary tale.

The sky outside Fan's window, cloudless and eggshell blue for days, suddenly darkens. A sandstorm has kicked up. Fan notices only long enough to remember the first project she undertook with one of the academy's longest serving partners, the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI). To prevent the kind of sand invasion that had buried some of the caves—and damaged paintings—GCI erected angled fences on the dunes above the cliff, reducing wind speeds by half and decreasing encroachment by 60 percent. Today the academy has dispatched bulldozers and workers to plant wide swaths of desert grasses to perform the same job.

The most painstaking efforts occur inside the caves. GCI has also set up monitors for humidity and temperature in the caves and is now measuring the flow of tourists as well. Its biggest project took place in Cave 85, a Tang dynasty grotto where GCI and academy conservationists worked for eight years devising a special grout to reattach mural segments that had separated from the rock face.

At a site this old, ethical ambiguities abound. In Cave 260, a sixth-century grotto that the University of London's Courtauld Institute of Art is using as a "study cave," Chinese students recently used micro-dusters to clean the surfaces of three small Buddha images. Almost invisible before, the Buddha's red robes suddenly sparkled. "It's wonderful to see the painting," says Stephen Rickerby, a conservator who is coordinating the project. "But we're ambivalent. The dust contains salts that can damage the paint, but removing the dust exposes it to light that will cause it to fade."

This is the dilemma Fan Jinshi faces: how to conserve the caves while exposing them to a wider audience. The number of tourists visiting Mogao reached more than half a million in 2006. The income has buoyed the Dunhuang Academy, but the moisture from all the breathing could damage the murals more than any other factor. Tourists are now limited to a rotating set of 40 caves, ten of which are open at any given time.

Digital technology may provide one solution. Following up on a photo-digitization project completed in 23 caves with the Mellon International Dunhuang Archive, the academy has launched its own multiyear marathon to digitize all 492 decorated caves (so far, the staff has completed 20). The effort mirrors an international push to digitize the scattered scrolls from Cave 17.

Fan's dream is to bring together digital archives from East and West to re-create the full three-dimensional experience of the caves—not at the site itself, but in a sleek new visitor's center proposed to be built 15 miles away. The center has not yet moved beyond the planning stages. But Fan believes that reuniting all of Mogao's treasures in one place, even virtually, will guarantee that their glories will never again be buried in the sand. "This will be a way," Fan says, "to preserve them forever."

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- We finally know how cockroaches conquered the worldWe finally know how cockroaches conquered the world

- Move over, honeybees—America's 4,000 native bees need a day in the sunMove over, honeybees—America's 4,000 native bees need a day in the sun

- Surveillance Safari: Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

- Paid Content

Surveillance Safari: Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa - Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

Environment

- Wildlife wonders: connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Wildlife wonders: connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

History & Culture

- Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?

- They were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendaryThey were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendary

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

Science

- Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?

- Scientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.RexScientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.Rex

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

Travel

- The ‘Yosemite of South America’ is an adventure playgroundThe ‘Yosemite of South America’ is an adventure playground

- These farmers make it possible for hikers to access Alpine trailsThese farmers make it possible for hikers to access Alpine trails

- A guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadowA guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadow

- How to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplingsHow to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplings