The toy aisle at Wal-Mart looked like some kind of ransacked mausoleum. In the four hours after Dale Earnhardt died, people had come and pillaged the diecasts, the model cars, the Hot Wheels recreations. In the men’s section, the Number Three hats and shirts were gone. In automotive, more of the same, all the way down to the “Piss on Dale” bumper stickers. Standing there, my dad grabbed my hand and squeezed it. We’d come down to the South Knoxville Wal-Mart off Chapman Highway to find something to remember Dale by, but the stone had already been turned. The body and all memory of it had been taken.

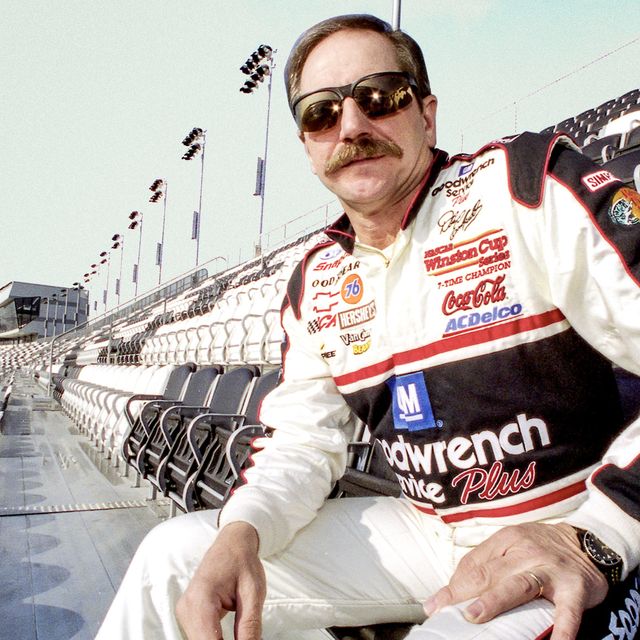

In the South in particular, NASCAR is akin to religion: church on Sunday morning, NASCAR on Sunday afternoon. Drivers are patron saints. Our house praised the works of Earnhardt. Two hours after his death, our dining room table had become a memorial to him—Dad had pulled out old mementos. A bent baseball cap. Some trading cards. A yellow and blue model car, from before Dale adopted his signature color scheme. In the middle, a NASCAR-licensed, black and red and white racing jacket with a big three on the breast. For most of the evening following that February 2001 Daytona race, Dad sat at the head of the table and surveyed all of it in silence. It was the first time I’d seen him cry. After a while, he asked me to head down the highway to Wal-Mart.

I cared a lot about Dale, but not in the same way as Dad. He’d found him in the ‘80s and adopted him as a role model. Ten years my dad’s senior, Dale hovered somewhere between father and older brother territory. He was driven and passionate and hot-headed. He encapsulated all those same qualities in my dad, but unlike the men in my dad's life, Dale gave him a healthy place to direct them. And then suddenly, after what appeared to be a harmless accident in turn four of the biggest race of the year, he was gone. The wreck was so unremarkable that Dad went to take a nap after it, bitching about Earnhardt’s ability to blow a top three spot in the final lap of Daytona. It wasn’t until later that we found out the wreck had been fatal. My mom woke him up when it was announced: Dale Earnhardt was dead.

Ever since, February 18 has been one of those lingering dates. You know the ones I’m talking about—dates that seem to leap off the calendar, magically highlighting themselves, as if your brain is wired to never escape the memory of a family member dying or a house fire or something equally tragic. Yet, it’s difficult to say, “I’m having a rough one. My hero died on this day.” I think we convince ourselves it’s not an acceptable grief, because we’d never met the person. They weren’t in our physical orbits. We might seem like we’re too invested. But being in this club, the Dead Heroes Club, is legitimate. It’s not about being a fan. It’s about losing a friend. A father-figure. The good thing that made you feel like you, too, could be elite.

The last time I recognized a death like that was about a year ago, when Kobe Bryant died in a helicopter crash. The thing about deaths like Kobe’s and Dale’s, or even Hank Aaron’s last month, is that there’s a unified, eulogic wave that sweeps the nation. Athletes occupy this particular place in our culture: Giants among men whose physical and strategic prowess exalt them to mega-human status. It’s why their demise also feels so startling. Then people show up to the metaphorical funerals with their metaphorical casseroles. Add in social media, and it becomes a cacophony of loss, with die-hard fans entangled in the same conversation as topical vultures. You’re forced to share this moment of loss with the rest of the world.

Then the news cycle moves on, and your pain remains. You don’t want to suggest that the rest of the world isn’t feeling sadness as hard as you’re feeling it, because all mourning is legitimate. You don’t want to be a dick, but when death comes so fast and unforgiving and the world is so fast and unforgiving, all you want is a moment to breathe without having to explain your grief to people who you're sure never felt it like you did. And when the sadness is online and performative like it so often is these days, you feel like that moment is being stolen from you. I watched a year ago as people joined the symphony of Kobe’s mourners, and I wondered if they knew him like his most fervent fans or whether it was a moment for engagement.

It makes me grateful that Twitter wasn’t a thing when Dale died. People were left to their own devices, to seek out closure in their own ways. Our local radio station announced that it would be setting up booths across town for Earnhardt fans, where, for five dollars, you could buy a commemorative CD honoring Dale’s life. On it were songs like Eric Clapton’s “Tears in Heaven” and Reba McEntire’s “If I Had Only Known,” spliced intermittently with recordings of Dale’s voice. The people who showed up to wait in line weren’t doing so for social clout. They were choosing to go to this impromptu receiving of friends, in the parking lot of a used Dodge dealership on the Airport Motor Mile, because they needed some place to say goodbye.

Waiting in line, people around us shared all their favorite memories from Dale’s career. My dad kept telling people that he'd heard that Dale’s final words over the radio were, “Look at them boys go,” referring to his son and running mate driving ahead of him moments before he died. I’ve spent years trying to confirm whether that’s true, never finding evidence that it actually happened. But sometimes that’s what people need. They need to be around their people, remembering their heroes. They need CDs with little clips of his voice. They need to sit with the emptiness and recognize it for the valid loss it is.

Join Esquire Select

I think we forget how real these connections are, especially now, when every headline is deemed breaking news. We urge ourselves to dismiss the grief that follows deaths like Dale’s, pushing it aside because we don’t know how to tell the people around us that a basketball player or a race car driver carved out a more prominent space in our lives than some family members. By the time we find the words, something else has happened. You’re left processing the loss of someone that defined a piece of who you are, which is already yesterday's news.

A few months back, my dad told me over FaceTime that he was clearing out his closet and found that black and red and white jacket. The one with the three on the breast. He held it up to the camera, and we sat quietly for a moment, in the same way that a photo of an old relative might take you by surprise. Then he said, “You know that’s going to be yours one day.” It may not make sense to you. He was just a man, right? Drove in circles while people drank cheap beer and cheered. It's just a sport. It's just a car. It's just a headline. But there’s nothing of my dad’s that I want more.

Justin Kirkland is a Brooklyn-based writer who covers culture, food, and the South. Along with Esquire, his work has appeared in NYLON, Vulture, and USA Today.