The origins of the Koran: From revelation to holy book

- Published

The Prophet Muhammad disseminated the Koran in a piecemeal and gradual manner from AD610 to 632, the year in which he passed away.

The evidence indicates that he recited the text and scribes wrote down what they heard.

Some of the Prophet's associates set out to collect into single volumes all the "suras" (chapters) that had been disseminated in this fashion.

This endeavour yielded a number of versions of the scripture belonging to different "Companions" of the Prophet, versions which today we call "Companion codices".

Shortly after the Prophet's death, different Companion codices became popular in different parts of the Muslim lands.

For example, in Kufa, a new town in southern Iraq, the popular codex was that of the Companion Ibn Masud who had gone to live there.

Standardization

The Companion codices were highly similar. For example, the sequences of verses within the suras were the same, and so were most of the words within the verses.

Nonetheless, some words and phrases were different.

The differences reflected the partially oral transmission of the text, which is to say they are of the sort we expect to see when an oral text is written down.

These differences sometimes affected the meaning, but they did not change the basic ideas of the Koran.

For example, they did not affect the scripture's notions about the nature of God or change major religious obligations.

Around AD650, the Caliph Uthman, who himself had been a close associate of the Prophet, had a committee establish an official version of the Koran based on the existing copies of the scripture and the knowledge of experts.

It is reasonable to conjecture that he worried about textual diversity and wanted to promote textual uniformity.

He sent this official version to different cities and people began copying it.

This Uthmanic textual tradition dwarfed and ultimately replaced the traditions of Ibn Masud and other Companion codices everywhere in the Muslim world, thus fulfilling Uthman's aim of greater textual uniformity from place to place.

Different readings

Uthman's act of standardization succeeded in reducing textual variation, but did not eliminate it altogether. The text established by Uthman accommodated multiple readings.

Because the script in which the early Korans were written lacked most of the vowels and marks that could distinguish several of the consonants, it was possible to read the text in different ways.

To be sure, oral tradition placed a check on variation, disallowing many otherwise feasible readings.

Nonetheless, numerous variant readings arose. Some of these affect the meaning, but none change the basic ideas of the Koran.

For example, reciters disagreed over whether verse 57 in sura 6 says God "tells" the truth (yaqussu) or "judges" truthfully (yaqdi), two words that look similar in the Arabic script. But since both ideas are ubiquitous in the Koran, the overall message of the scripture is not affected by either reading.

From the above, it is evident that Muslims have lived with a measure of diversity within an otherwise largely stable and uniform text since the beginnings of Islam.

Muslim theologies have assimilated this historical reality in various ways.

While opposing opinions have always existed and persist today, the predominant view has been that the different versions and readings of the Koran that are traceable to early Islam all enjoy God's endorsement.

This idea was embodied in the early statement that God revealed the Koran in multiple forms, and it was fleshed out later by authors such as the 15th-Century scholar, Ibn al-Jazari.

New insights

For many centuries, there has been a rich and sophisticated tradition of Koranic scholarship. However, it is in the nature of knowledge to evolve.

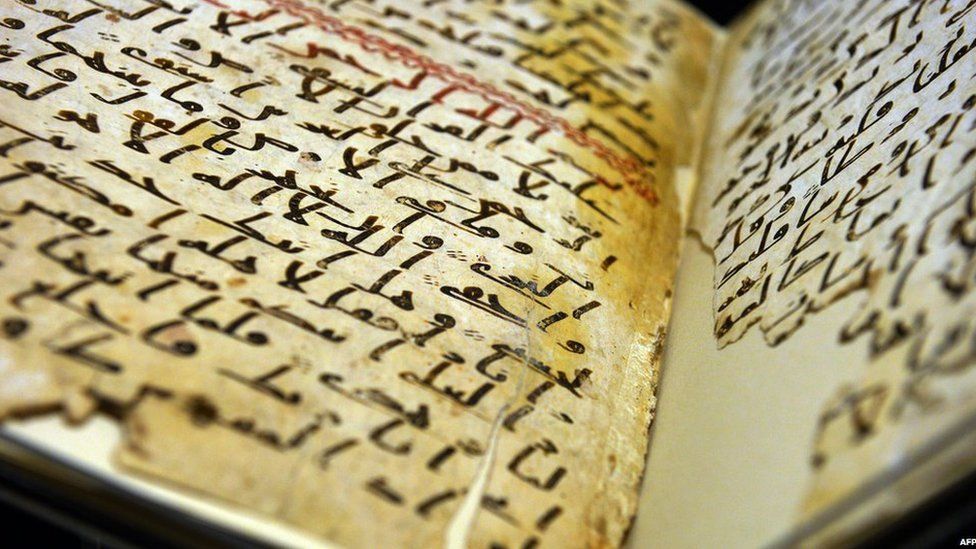

Early Koranic manuscripts present one of the resources that can add new insights and nuance to our knowledge of the text's history.

Radiocarbon dating, thanks to technical advances in recent decades and the rigorous efforts of numerous scientists, has developed into an effective and accurate way of dating manuscripts, particularly when performed at the best labs, such as those in Oxford, Arizona, and Zurich.

However, experimental error can creep into the work of the best scientists.

One can control for error by testing more than one sample from a manuscript.

Several tests on a Koranic manuscript called "Sanaa 1" (including a new test that Mohsen Goudarzi and I will publish soon) have dated it to the first half of the 7th Century.

Researchers continue to test more and more manuscripts, many of them datable to the first century of Islam. All of this presents a pleasing prospect for Koranic scholarship.

Behnam Sadeghi is an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Stanford University and specializes in the early centuries of Islam. He is the author of The Logic of Law Making in Islam: Women and Prayer in the Legal Tradition, published by Cambridge University Press in 2013.

- Published22 July 2015

- Published4 October 2021