We’re all curious about what might hurt us.

―Federico García Lorca

The Benedict Canyon house was demolished years ago. A church looks down on the old ranch, which is now a state park. Most everyone who fell under his thrall is dead, or aging quietly in prison.

None of that matters. The further events recede into history, the longer their shadow looms, and that of their dark progenitor.

That’s the way it is with myth. With the stories that we tell each other, that we’ve handed down since before we huddled around the cave fire at night, seeking safety from predators. Those fables were filled with gods, mortals, evil, good, power, and forbidden pleasures; they were meant to teach us and scare us and set us on a path of righteousness.

But what if all this time we were just tricking ourselves, thinking the danger was out there in the dark and we were safe inside.

What if the predator has been in the cave with us from the beginning?

What if he is inside us?

This story is real.

It happened 50 years ago, during the extended hangover that followed the Summer of Love. Joan Didion said that it slammed the door on the 1960s. But the decade was already on life support.

You all know his name. He was born elsewhere, in obscure poverty, but, like so many, was drawn mothlike to the lights of Los Angeles, the possibility of shedding the past, reinventing himself, and claiming the fame and fortune this city has always dangled before dreamers with the wiles of a femme fatale.

Here, he began the metamorphosis from petty crook to Hollywood-adjacent wannabe to L.A.’s ur-demon.

This couldn’t have happened in Des Moines or Fairbanks. It could only have taken root in the nutrient sludge of sex, rock and roll, trust funders, drugs, outlaws, movie stars, crime, mysticism, and hippie flower power that defined ’60s L.A.

And there it bloomed like a noxious weed—in the remote sandy canyons of the Simi Hills, the rarefied green of Bel-Air, the historic hotels, recording studios, and boulevards of Hollywood and the Sunset Strip.

This article was featured in Alta Journal's free Weekend Read newsletter.

SUBSCRIBE

It fed off a society in turmoil, where the old and new orders clashed and trust in institutions eroded daily. It required the kind of upheaval that we see today, as a new reality-altering drug drips into our veins—the internet.

Maybe that’s why now, 50 years on, the tale only resonates more profoundly.

He didn’t kill anyone.

He enslaved the will of others so completely that they did it for him, laughing and chanting as they stabbed with their steely knives, grateful to be chosen. More than anything, that’s what repels us, even as it draws us in. And that’s why he tops the demonic pantheon, muscling out L.A.’s more prolific serial killers—the Hillside Strangler, the Night Stalker, the Grim Sleeper.

The press had to manufacture lurid nicknames to amplify their notoriety. He didn’t need that kind of help. Our L.A. demon had only one name—his own.

Manson.

He finally died in 2017, after surviving almost a half century behind bars. But as we’ve learned from zombie and vampire flicks, it’s hard to kill the undead.

We are complicit in stoking his myth. Greedily we seek answers: Why did he? How could they? Was it drugs? The mob? The government? The cops? Was it premeditated, or a robbery or drug deal gone wrong? Conspiracy theories swirl around our nightmare-encrusted brains—as they did around his.

Many of us faced dark times, dreamed of remaking the world, sought answers. Would we have fallen prey to him? To the promise of insta-family, free love, a communal utopia? Would our children have?

Will the day ever come when his legend crests, then slowly dwindles until he’s reduced to a bug-eyed avatar of pop evil, screaming his helter-skelter gibberish into the void?

Probably not.

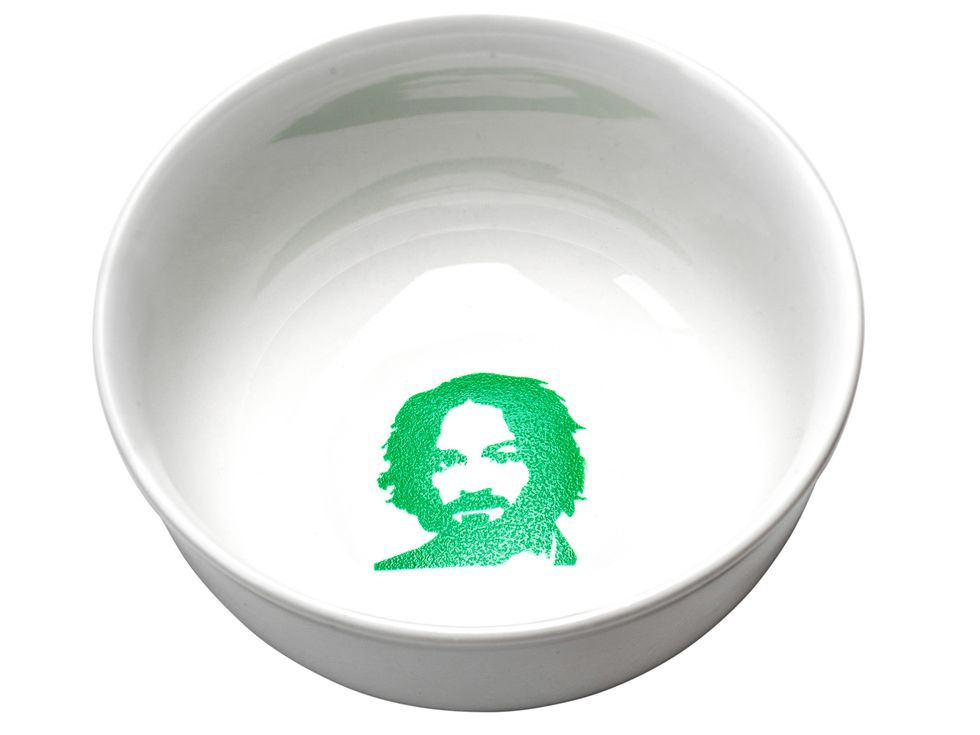

Not when each year brings new books, movies, TV shows, songs, websites, podcasts, YouTube videos, bus tours. Not when there’s still such a robust Manson merch market online—from T-shirts and coffee cups to his jailhouse flip-flops (asking price: $5,000) to white infant onesies emblazoned with his scrawny, hairy image and that evil stare.

Manson.

The truth behind the Manson Family’s crimes is even weirder, darker, and more complicated than you know.

—Description of Esotouric’s Mansonland Bus Tour

On an overcast day in late winter, I clamber aboard the bus.

The Manson bus.

Not the beat-up one the family lived in. That’s long gone.

This black luxury liner tour was dreamed up by married cultural historians Kim Cooper and Richard Schave, founders of the sightseeing company Esotouric. During our four-hour expedition, we’ll visit Manson-related sites while guest host and author Brad Schreiber’s lecture connects our demon to organized crime, drug dealers, Black Panthers, sex workers, and motorcycle gangs.

Cooper and Schave also lead tours that reveal Los Angeles through the eyes of Raymond Chandler, the Black Dahlia, and Charles Bukowski. They’re all popular, but this one is off the charts. It sold out so fast they added a second one. That sold out too.

I scan my fellow tour-istas for Manson groupies. But all I clock are curious Angelenos from 20 to 70, loaded down with snacks and water bottles, cheerfully embarking on a descent to the dark side.

I meet the 30-ish daughter of cops whose parents told her all the stories. A techie in a Manson T-shirt who complains that people don’t remember him anymore. A young true crime fan with her aunt. A woman from the West Valley whose brother used to pick up the Manson girls hitchhiking. She has friends who were “creepy-crawled” by the Manson family—those practice runs they’d make, breaking into homes, prowling around, and leaving traces that they’d been there.

“That was my time,” she says. “This is my history.”

Our first stop is El Coyote, an L.A. classic known more for its strong fishbowl margaritas than for its food, where Sharon Tate ate her final dinner with friends.

As we hurtle through the city’s past, we use our smartphones to augment the lecture, making the years stretch and double back like poison taffy. I scroll through photos of the trial, then glance out the window, where the sun is trying to emerge from the clouds. We pass a Starbucks, and suddenly the coffee mermaid warps into a wild-haired Manson girl.

We turn onto Fairfax. A guy talking to himself on the street sports the long hair, beard, wild eyes, and amphetamine physique of a 21st-century Manson. Does he also preach race wars and Armageddon? A billboard for a Netflix comedy suddenly feels less innocuous: “Turn Up Charlie,” it warns us. “Tables Will Be Turned.”

It’s just a coincidence, man.

We pass what was once a hair salon owned by Jay Sebring, one of the inspirations for the film Shampoo, who was murdered with his friend and former lover Tate on Cielo Drive. The salon’s gone, but the words “Dolls Kill” are scrawled, graffiti-style, on a nearby storefront. It’s only the name of a shop, not a reference to Manson’s girls. At least the letters are white, not written in blood. They don’t say “Pig.”

The sun emerges, lighting up the Hollywood sign like the Promised Land. Then gloom descends once more and we drive into darkness. It’s 1 p.m.

Los Angeles is beaming secret messages to me, its native daughter, on a wavelength that hasn’t existed for 50 years.

We’re on Hollywood Boulevard now, passing the renovated Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, where the first Academy Awards were held in 1929. By the late 1960s, it had fallen on such hard times that Manson was running prostitutes there.

We zigzag onto Franklin Avenue, and our guide points out the site of a long-demolished fleabag apartment where Manson once lived. Now it’s a parking lot. I think about how so much of L.A. has been bulldozed and rebuilt. The old landmarks, famous and infamous. And yet their afterimages are seared into our collective retinas. Eyes wide shut, we reconstruct them, visit them, summon their ghosts. And we shiver.

Later, Cooper and I discuss Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia, whose dismembered body was found in a Crenshaw bean field in 1947. Just as Manson epitomized the excess of the ’60s, the Black Dahlia was a cautionary tale for the film noir ’40s.

“They’re both blank slates,” Cooper muses. “Anything you want to know about the 1940s, Beth Short can be it. A hustler, a semi-prostitute, an actress, this good girl who was mentally disordered by grief. In the same way, Charlie can be a victim or a monster. He can be a total charlatan or a maniac. You can project anything onto them that you want. Their personalities were performative.”

“I am only what you made me,” Manson taunted the world. “I am only a reflection of you.”

I don’t remember the Manson killings, but I read my parents’ copy of Helter Skelter like all my friends. For years, I gave long-haired hippies of both sexes a wide berth. There were still Mansonites around, including Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, who tried to kill President Ford in 1975. Like the black goo that bubbles up from the La Brea Tar Pits, they emerged from cracks in the ground to wreak havoc.

Manson even tainted my love of the Beatles, though I never heard the black uprising Manson divined in “Blackbird.” Nor did the proto-punk delivery of “Helter Skelter” inspire anything in me but spasmodic flailing, which I’d perfect in L.A. clubs.

Later, working as an L.A. Times reporter and passing the Hall of Justice, I pictured the Manson girls walking the corridors with their carved-X foreheads, shaved heads, and tatterdemalion outfits. They were modern Furies from Greek myth, flickering behind spacey smiles. Manson was Loki, the trickster god who could slip his chains and disappear into the ether. Lo and behold, he did, returning as the ghost in the machine called the internet. In his old age, he even found a new Manson girl to adore him and shave off her hair, a 20-ish daughter of Missouri Baptists called Star who moved to Corcoran to be near him.

This is the closest to Pulp Fiction that I’ve done.

—Quentin Tarantino, on Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood

Bus tours are but a sliver of the pop culture juggernaut that is Manson Inc. The movies, books, reportage, podcasts, websites, musicals, and even an opera continue to arrive. In the 2015 film Manson Family Vacation, two dysfunctional brothers tour Manson crime sites while trying to bond. In a recent TV series, Aquarius, David Duchovny plays an LAPD detective in 1967 tracking down a missing teen girl who has joined the Manson family. Karina Longworth’s excellent podcast You Must Remember This devoted an entire season to Manson. Numerous novels use the crimes as backdrop (Steve Erickson’s Zeroville) or explore growing up in a Manson-like cult (Emma Cline’s The Girls). The angles and approaches to the 50-year-old story are as inexhaustible as our imaginations.

From June to November last year, L.A. residents might have thought they’d stumbled through a portal into late-1960s Tinseltown.

That was when the Quentin Tarantino show rolled in. Bygone restaurants, shops, and movie theaters like the Pussycat and the Vogue were magically re-created along stretches of Sunset and Hollywood Boulevards, and the sidewalks were thronged with long-haired girls wearing miniskirts, boots, and crochet purses and long-haired guys with bandannas, peace beads, and muscle cars.

Tarantino has been secretive about his new film, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood, which opens July 26, except to say that it’s not about Manson. The film follows a cowboy actor and his stunt double buddy (played by Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt) as they navigate a rapidly changing Hollywood that no longer embraces westerns. The cast includes Australian actor Damon Herriman as Charlie, as well as Dakota Fanning as Manson follower Squeaky Fromme. Oh, and DiCaprio also happens to live at the top of Benedict Canyon, on a street called Cielo Drive, next door to a beautiful blond actress named Sharon Tate (portrayed by Margot Robbie). So yeah, plenty of Manson, though perhaps the biggest fantasy for us in 2019 is a fading cowboy who can afford Benedict Canyon.

The film captures a world, like Manson’s, in which fame was always tantalizingly close, or fleeting even when you reached it. Spahn Ranch was a 1920s-era western set that was being used mainly as a horse ranch when Manson lived there. Several filmmakers wanted to make documentaries about his family’s hippie lifestyle. Manson’s associates knew experimental filmmaker Kenneth Anger and had been active on the fringes of the film and music worlds.

But the big break never came. And so, eaten away by hate and jealousy, lusting for revenge and power, Manson took a different path.

There’s a time for living

Time keeps on flying

Think you’re loving baby

But all you’re doing is crying

—Charles Manson, “Look at Your Game, Girl”

Manson was a crap musician and songwriter. But the course of history might have been different if he’d made it in rock and roll.

He got several shots in 1968, when Beach Boy Dennis Wilson picked up two Manson girls hitchhiking on Sunset and brought them to his Pacific Palisades mansion for a romp. Within weeks, Manson and his family were living there and tooling around town in Wilson’s burgundy Rolls-Royce. Wilson liked Manson’s guitar playing and got him a recording gig.

He even introduced him to Terry Melcher, the record producer son of Doris Day, who ultimately declined to sign Manson. Maybe he thought Manson stank. Maybe he’d heard about how Manson had pulled a knife in the studio because he didn’t like the way Wilson’s team wanted to change his music.

Despite his lack of musical chops, Manson managed to achieve rock infamy decades later. Guns N’ Roses covered his song “Look at Your Game, Girl” as a hidden track on their 1993 album The Spaghetti Incident? Brian Hugh Warner won multiplatinum success after taking the stage name Marilyn Manson and working snippets of Charlie’s lyrics into his debut.

The Beach Boys and Nine Inch Nails sit at opposite ends of the musical spectrum, but they both drew inspiration from Manson.

Listening to the dulcet harmonies on the Beach Boys’ “Never Learn Not to Love,” a reworking of Manson’s “Cease to Exist,” is spooky. This is not the tender melancholy of Pet Sounds. A dissonant specter hovers over it.

Dennis Wilson spent only one mad summer with Manson, then fled into the arms of more traditional demons. A generation later, Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails submerged himself in the macabre by moving into 10050 Cielo Drive to record his landmark 1994 album The Downward Spiral.

Reznor claims—somewhat disingenuously—that he didn’t know it was the Tate house when he moved in. Still, he embraced the setting, hoping to infuse his already dark music with some Manson juju. He christened the home studio he built there Pig, the word a Manson girl had scrawled in blood across the front door the night of the murders. When Reznor moved out, he took the door as a souvenir.

“I’d come home and find bouquets of dead roses and lit candles in the front gate,” Reznor said at the time. “It was really eerie. Who were they leaving the shrines for: Tate or Manson?”

The ghosts claimed their pound of flesh. Reznor entered his own downward spiral of drugs and depression, though the album would go on to be a worldwide hit and defining sonic moment of the 1990s.

As for Manson’s music, you can judge for yourself. If you download his songs, profits go to the son of Wojciech Frykowski—the Polish filmmaker murdered along with Tate—who won a court judgment against Manson. Other tape-recorded Manson songs have also surfaced.

Manson realized at least one of his goals: his music is better known today than ever, his songs recorded by global superstars and disseminated online.

As for Le Pig, it was torn down with the house in 1994. The owner built a new house and had the street address changed, but people still arrive daily to view and ponder the blood-stained earth.

Manson’s eyes glittered when he looked up at me. I was not what he expected. I was darker than assumed, a full head taller and outweighed him by 80 pounds…. His angular face and sable shoulder-length hair gave him the look of a shrunken, wily-eyed Christ…. He asserted he wasn’t a racist but a realist…. Didn’t I realize that what Nietzsche wrote wasn’t intended for the likes of me? Especially the part about a race of Supermen?

—Wanda Coleman, “Love-Ins with Nietzsche”

In the summer of 1968, a young African American poet often spent time with her family in Griffith Park. One day, her musician husband, who was white, told her they were moving their blanket to “Charlie’s” tent.

When Manson saw she had a book by Nietzsche, he asked to borrow it and, to her surprise, politely returned it two weeks later, after which they debated black revolution. In a 2000 chapbook, Wanda Coleman recalls that conversation.

“Manson maintained that if…revolution of any kind was to take place in the U.S., only Whites could defeat Whites because Blacks—if Martin Luther King were any example—did not have the guts or the intelligence to lead either an armed or organized resistance.”

At this, Coleman left. But at his urging, she also went to “check out his women.”

“Two of the dazed-eyed naiads took me by the arm and led me to the women’s quarters…. They liked playing with our kids. But I could not connect. We had nothing in common. Their sole interest was their reverence for their Charlie. They spent hours discussing his needs, wants and lessons. Otherwise, they seemed spaced out, or high—flitting about without ambition or purpose. I had no experience with the drug culture and no way of understanding who they were.”

Manson also invited Coleman to Spahn Ranch and promised her husband much-needed work. He went alone and returned empty-handed. Manson and his followers were bad people, he told her, and the “work” was stealing cars.

It wasn’t until the following year that Coleman learned how bad Manson was, and that he had hoped the Tate-LaBianca murders would trigger a race war that his family would sit out in the desert. (Indeed, he was captured at Barker Ranch in Death Valley.) In Manson’s worldview, black people would win the race war, then invite him to rule over them after being unable to govern on their own.

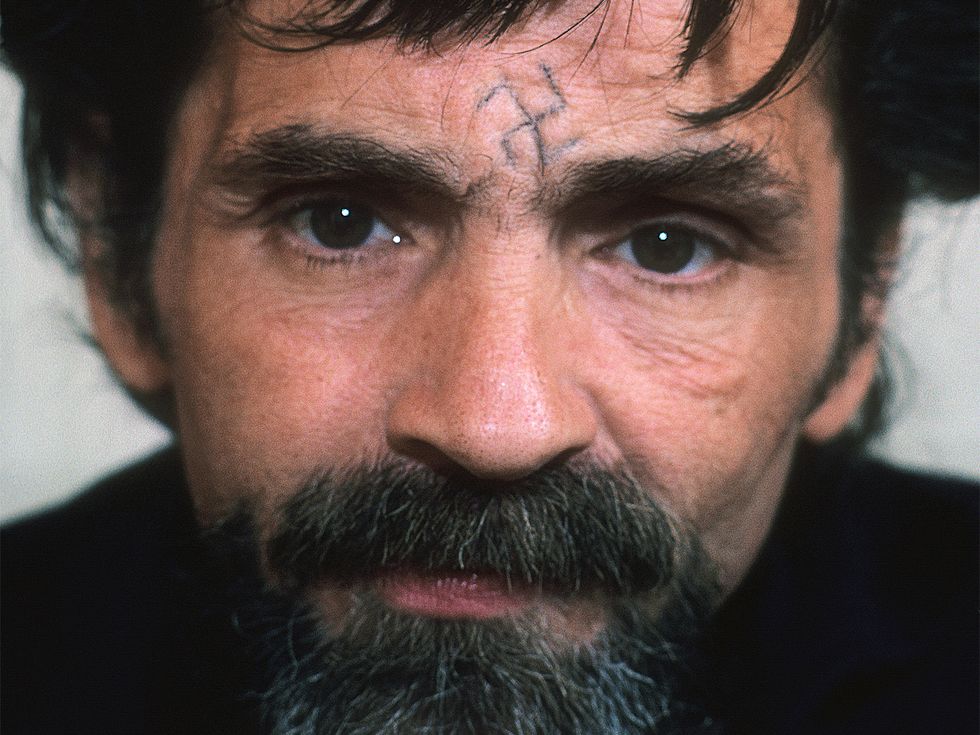

Coleman’s chance encounter underscores what was initially downplayed owing to his more sensational crimes. Despite his denials, Manson hated and feared African Americans. The swastika carved between his eyes? A big fuck-you to the world, yes, but it, too, revealed his racism.

Manson’s apocalyptic notions weren’t even original; they were cobbled from the beliefs of previous cults, gurus, and charlatans who had infested the region almost since the pueblo’s founding.

“Paradoxical in all things, Southern California is a land of exaggerated religiosity and also of careless skepticism, where old faiths die and new cults are born,” wrote historian Carey McWilliams in the 1946 classic Southern California: An Island on the Land.

That included the followers of Krishna Venta. When Manson moved to Spahn Ranch, he found remnants of this utopian cult living one hill over in Box Canyon, where since 1949 white-robed vegetarian adherents had farmed and kept goats and sheep. Their wild-haired, barefoot group had followed Krishna Venta, “the Master,” who preached an American Armageddon in which all but his disciples would be destroyed in a race war. Marriages were sexless, but Krishna Venta slept with a different female member each night and snuck off to L.A.’s Sodom for gambling sprees. In 1958, two male followers confronted Krishna Venta, and a bomb they were carrying exploded, killing all involved.

Cooper and Schave, who have researched the cult, say that Manson spent time with the Krishnavantas and absorbed their ideas. The site has passed through various owners’ hands since the 1960s. According to newspaper stories, the area is a stronghold for an anti-government conspiracy group called Sovereign Citizens. A decade after the Manson murders, his paranoid quasi-religious prophecies found new expression in the racist, anti-Semitic novel The Turner Diaries and the string of white power massacres that began with Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building, which killed 168 people. Manson was just ahead of his time.

Merry Christmas Charlie Manson

—South Park

It’s been 21 years since the South Park episode in which cartoon Manson breaks out of prison with Eric’s uncle and spends the Christmas holiday with the Cartman family, where he finally learns the error of his ways and converts the swastika tattoo into a smiley face. When the cops arrive, Manson surrenders. He knows he belongs in prison.

It seems that each generation gets the Manson it deserves. Drug-addled hippie Manson. Goth Lucifer music Manson. And today, white supremacist, Hollywood, and defanged cultural influencer Manson.

It’s easy to gloss over the real-life costs of pop culture’s breezy embrace of a sinister and murderous cult leader. Debra Tate, Sharon Tate’s sister, who became an advocate for victims’ rights after her sister’s murder, is dismayed by the attention lavished on Manson, instead of on his victims. She once confronted Trent Reznor, accusing him of using the murders for malevolent publicity. She isn’t happy about the Tarantino movie, either.

As Tate told TMZ, “To [celebrities] it’s a paycheck and these people just don’t care. They are terribly hurtful to the actual family and all the living victims. They don’t give a shit.”

But sadly, Tate is fighting the darker side of human nature.

Manson is a virus, and we’re all infected.•

Denise Hamilton is a Los Angeles native, crime novelist, and former reporter for the Los Angeles Times. She’s the editor of Los Angeles Noir and Los Angeles Noir 2: The Classics and was a finalist for the Edgar Award. Read more about her at denisehamilton.com.

![ATA070219manson_img08 A still from a 1998 episode of the cartoon [em]South Park[/em], in which an animated Charles Manson breaks out of jail and learns the error of his ways.](https://hips.hearstapps.com/altaonline/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ATA070219manson_img08.jpg?resize=980:*)