Watching a great performance can be like falling through a mirror—not seeing yourself reflected, exactly, but feeling a ripple of familiarity as the character’s experience washes over you. But try that trick with Natalie Portman, and you’ll find yourself smashing your nose on cold, hard glass. For an Oscar-winning actress who’s been hailed as one of the greats since she was a child, Portman is a singularly removed performer, always keeping the audience at arm’s length. Some actors disappear into their characters; Portman stands outside hers, sizing them up with a clinician’s eye. She can, and frequently does, register as a chilly technician, note-perfect but hollow. But she comes alive when she’s playing characters who are in the same predicament as her, trying to perform a part and not quite managing to pull it off. When it comes to playing a bad actress, there’s no one better.

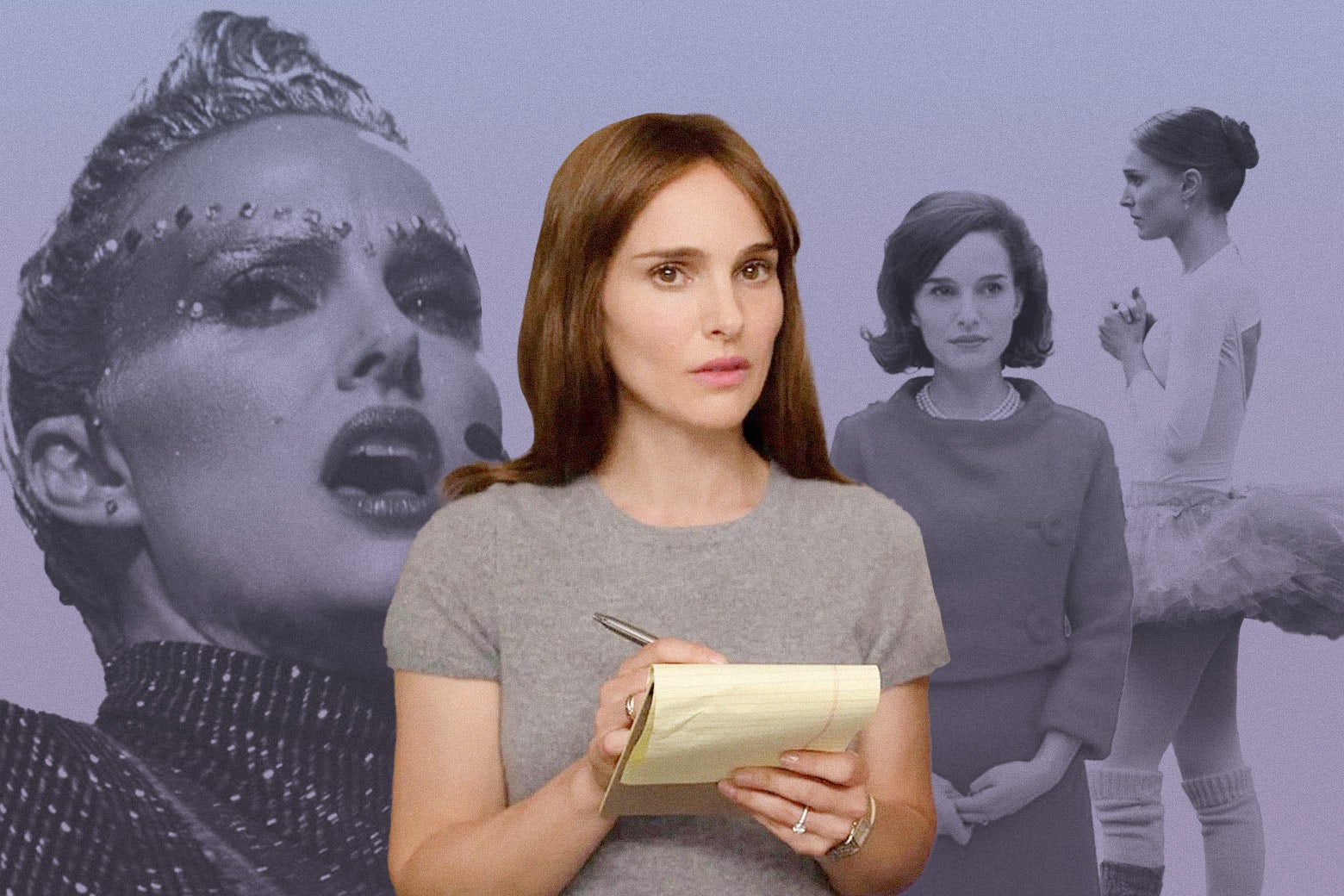

You can see Portman playing people who are trying to play other people all throughout her career: as the bereaved first lady putting on a mantle of stoicism in 2016’s Jackie, or the sex worker who swaps partners as easily as she does hairstyles in 2004’s Closer. But it’s been a long time—since 2010’s Black Swan, to be precise—since she’s taken on a role as explicitly concerned with the nature of performance as her part in director Todd Haynes’ May December, which begins streaming on Netflix on Friday.

In May December, Portman plays Elizabeth Berry, a TV star who’s attempting to make the transition to serious acting by playing the lead in a movie about Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore), a pet shop employee who was jailed for having sex with a seventh grader.* (Samy Burch’s screenplay is inspired by the real-life case of Mary Kay Letourneau, who died in 2020.) Twenty-four years later, Gracie and Joe (Charles Melton), who’s now in his mid-30s, seem to be happily married, preparing to send the last of their three children—the first of which Gracie was carrying when she went to prison—off to college. But Elizabeth’s arrival in sleepy Savannah, combined with the prospect of the couple facing each other without the buffer of children for the first time in decades, stirs up unresolved issues, not least of which is whether 13-year-old Joe was as consenting a part of their sexual relationship as he’s always believed himself to be. Elizabeth both foments and feeds on their unrest, pouncing on every opportunity to peek behind Gracie’s blandly welcoming facade.

As she pores over vintage tabloids recounting the details of Gracie’s past (“BABY BORN BEHIND BARS”), we hear Elizabeth’s notes aloud: “Eyes round … pointy … closed when they’re open. … Mechanical, or just removed?” It can’t be an accident that Haynes, the metatheatrical master behind I’m Not There, Far From Heaven, and Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, has cast as Elizabeth an actress of whom you could often ask the same question. When she’s playing a person with nothing to hide, who simply is who she claims to be, Portman can feel like an honors student stuck in a remedial class, going through the motions while her attention is elsewhere. But give her a more complicated equation, and she sets her entire intellect to solving it.

That’s not the same as throwing herself into a role. In fact, the more you watch Portman, the less clear it is that you’re ever seeing a glimpse of the real her. Movie stars tend to build their careers around a core personality—Tom Cruise’s cocky determination, Margot Robbie’s kewpie-doll subversions—but Portman’s star persona has no core at all, or at least not one we’re allowed access to. In 2018’s Vox Lux, she’s Celeste, a Gaga-esque icon who entered the public eye as the survivor of a school shooting, leveraging her notoriety to build a career singing vapid pop songs to bridge-and-tunnel crowds. Portman plays the adult version of the character with a conspicuously artificial Staten Island accent, and although she says that she’s “sick of everybody treating me like I’m not a real person,” it’s not clear the movie believes that she is one. As Celeste prepares to go onstage for the extended concert sequence that closes the film, we catch a glimpse of her eyes, and there’s nothing behind them. Singing isn’t how she expresses who she is. It’s how she avoids having to be anything at all.

In Black Swan, Portman’s Nina is a ballerina who’s given her entire life to dance, so much so that she barely seems to exist outside it. She still lives with her domineering stage mother in a bedroom that looks as if it hasn’t been redecorated since the third grade. She’s flawless, but also lifeless, as precise and predictable as a music-box figurine. “Perfection isn’t just about control,” her company’s director, Thomas (Vincent Cassel), instructs her. “It’s also about letting go.”

Although Portman admits that The Professional, in which she played the 12-year-old protégée to a middle-aged hit man, looks awfully “cringey” these days, especially in the light of sexual assault allegations against director Luc Besson, she’s also said that her experience as a child actress was a largely positive one, without the trauma that seems to freeze some child stars’ emotional development at the moment they enter the public eye. (The way male directors sexualized the teenage Portman isn’t not like the way May December’s Gracie treated Joe, and Melton often plays him as if he’s a 13-year-old in a 36-year-old’s body.) Still, it’s not hard to see echoes of Portman’s life, or at least the life she might have lived if she had less conscientious stage parents, in Black Swan’s portrait of a child prodigy whose pursuit of external perfection has come at the expense of any connection to her inner self.

Even decades into her career, there’s still a touch of the precocious kid actor about Portman, a tendency to display technique for its own sake rather than use it as a tool of personal excavation. Nina is desperate to land the lead in a production of Swan Lake, but there’s a catch: Thomas wants the same person to dance the part of the virginal White Swan and her dark and earthy double, the Black Swan. If it were only a matter of casting the former, he tells her, she’d already have the part. But instead, she’s forced to compete with Lily (Mila Kunis), a new dancer who possesses only a fraction of Nina’s technique but is far more in touch with her primal self. Nina may be “perfect,” Thomas tells her, but when Lily dances the lusty black swan, you can tell “she’s not faking it.”

We don’t get to see May December’s Elizabeth act in front of a camera until the movie’s final scene, but Haynes keeps dropping hints that she may not even be all that talented. Her Juilliard training may be enough to impress a high-school drama teacher, but her biggest claim to fame remains playing the lead on a popular TV show called Norah’s Ark, which sounds like a version of Grey’s Anatomy set in an animal hospital. Apart from a glimpse of a skin-care commercial, where she does indeed look suitably luminous, the only other evidence of Elizabeth’s career is a snippet of a nude scene discovered online by Joe’s creepy neighbor. She does her best to play the role of a serious actress, mouthing platitudes about how she’s studying Joe and Gracie in the hope of being able to portray “something true” about their relationship. But Gracie sees right through her, in part because her life is a sustained performance of its own. On the outside, Gracie is unflappable, maintaining a chipper veneer even when a box of human excrement shows up in her mail. Behind closed doors, she frequently bursts into sobs, over matters as small as a longtime customer canceling an order from her cake-baking business.

Elizabeth keeps saying that she wants to make something real, but there’s no indication that she’d recognize the truth if she saw it—or if, indeed, there is such a thing. (In one especially Haynesian aside, she mentions that her mother wrote “a pretty respected book on epistemic relativism,” a branch of philosophical thought in which the validity of knowledge is determined entirely by its context.) She copies Gracie’s mannerisms, including her pronounced lisp, and even learns to do her makeup the same way, as if mimicking her subject’s outsides will reveal her innermost secrets. But Elizabeth can’t see beyond what Haynes’ Far From Heaven called “the surface of things,” because she’s all surface herself. Gracie, who’s spent two decades convincing herself that it was her 13-year-old student who seduced her, has buried her sense of culpability, but you can feel that it’s still there, somewhere. Inside Elizabeth, there’s nothing but need.

Portman’s version of Jackie Kennedy is more like Gracie than she is like Elizabeth, in the sense that she has access to her emotions but they are hers alone. In a private moment after JFK’s assassination, we see her breaking down on Air Force One, her face streaked with tears and her husband’s blood. But in front of others, she is always performing. Whether she’s speaking to a reporter, stage-managing her husband’s funeral, or leading a TV crew on a tour of the White House, she’s hyperaware of how she’s being perceived, and in the rare instances when she drops her guard, she quickly reminds her interlocutor that it’s to be kept off the record. Portman doesn’t look much like the real Jackie, and her mid-Atlantic accent is every bit as affected as Jackie’s, but that’s part of what makes Portman’s performance so strangely moving. This isn’t a woman who can ever just be.

What matters, Portman’s Jackie makes clear, isn’t what’s real. It’s what people see on television, the self-image she creates and controls. In movie after movie, Portman’s characters come face-to-face with a vision of themselves, but their reflections don’t always play by the rules. In Black Swan, the mirrored walls of a dance studio produce an infinitely receding procession of Ninas, one of whom steps out of line with a menacing sense of autonomy. At the end of Annihilation, Portman’s character meets an alien doppelganger with shimmering skin that first takes on her form and then threatens to absorb her. And in Vox Lux, a group of terrorists stages a mass shooting wearing costumes taken from one of Celeste’s music videos: masks made out of mirrors.

The most profound exchanges between May December’s Elizabeth and Gracie also take place in front of a mirror, but instead of seeing their reflections, we just see them, staring out toward the camera as they stand in front of a bathroom sink. For all of Elizabeth’s dedication, they don’t look much alike, and between the two of them, it’s clear that Gracie, the predator who’s played the wronged woman for years, is the more convincing actress. But Elizabeth’s failure is Portman’s greatest achievement. Her emptiness makes a place for us to find ourselves, and to reflect on how impossible it is to truly know what’s inside anyone, no matter how closely we watch.

Correction, Dec. 4, 2023: This article originally misidentified Julianne Moore’s character as a former schoolteacher.