Gummo

When Harmony Korine’s Gummo crept into theaters like a scabby thief in the night, it was greeted with the sort of critical violence that always makes me want to see the movie for myself. Sometimes a universally hated film is universally hated for a reason, and I’ve gotten stung at such movies as Even Cowgirls Get the Blues and North. But other such despised movies, like Crash and A Life Less Ordinary, made me wonder if the entirety of American critics had seen the same film I saw. We say we want something different, and yet when a film actually gives us that, we punish it, mock it, call it pretentious and pointless.

When Harmony Korine’s Gummo crept into theaters like a scabby thief in the night, it was greeted with the sort of critical violence that always makes me want to see the movie for myself. Sometimes a universally hated film is universally hated for a reason, and I’ve gotten stung at such movies as Even Cowgirls Get the Blues and North. But other such despised movies, like Crash and A Life Less Ordinary, made me wonder if the entirety of American critics had seen the same film I saw. We say we want something different, and yet when a film actually gives us that, we punish it, mock it, call it pretentious and pointless.

My honest opinion? I liked Gummo. That surprised me, since I’m not a big fan of Kids, the overhyped 1995 film that Harmony Korine wrote (Larry Clark directed it). Kids tried to be an old-fashioned cautionary tale dressed up in new-shit hipster clothes; the result was a shrewdly posturing work — a film that young urban moviegoers could attend and pretend they’d walked on the wild side. Gummo, which Korine wrote and directed, is closer to the real thing. If it were a documentary, Korine would be hoisted up there alongside Errol Morris and Terry Zwigoff as a filmmaker who captured the chaos of inner life. Because it’s fiction, Korine is denounced as an exploitative brat with a camera.

What’s really going on here? Seems to me a lot of urban baby-boomer critics have a knee-jerk aversion to any work that shows poverty-stricken rural people but doesn’t serve up a clearcut uplifting message (banks are bad, farms are good, the community will always pull together, etc.). Gummo is set in Xenia, Ohio, a town that never recovered from a tornado. (It was shot in Nashville, though.) The two main characters are Tummler (Nick Sutton) and Solomon (Jacob Reynolds), two aimless kids who kill cats so they can sell them for meat and buy glue to huff. Korine regards them neutrally, without comment, and he treats everyone else onscreen the same way. That this is condemned as condescension, and not merely depiction, shows the condescension of the critics — the same well-to-do critics who hate Jerry Springer because its guests are supposedly too ignorant (i.e., too small-town) to know they’re being exploited.

Working with cinematographer Jean-Yves Escoffier (Good Will Hunting), Korine sustains a depressive mood, a world of muted colors and no expectations, a place where entertainment consists of watching two men beat up a kitchen chair. Some may ask why we’d want to watch such things. Me, I think it’s a relief. When a film like Crash or Gummo comes along that’s so not Hollywood, so not about cute people with cute flaws and happy endings, we Americans, who claim to be sick of the same action movies and romantic comedies, have the gall to complain that movies like Gummo have no story. Well, the non-story in Gummo interested me a hell of a lot more than the non-stories that Hollywood passes off as stories.

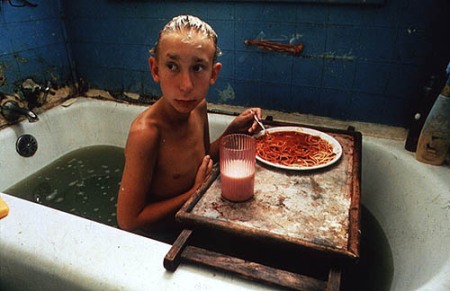

And Korine is a far more inventive visual filmmaker than his one-time director (and photographer) Larry Clark ever was. That famous shot of Jacob Reynolds eating spaghetti in a tub full of gray bathwater puts a slippery finger on a part of your brain that usually isn’t touched. The movie is full of such bothersome, elusive images (a kid with pink bunny ears strolling across a bleak landscape; a mentally disabled woman shaving her eyebrows; two skinheads pummeling each other — for real; the sight of Out of the Blue‘s Linda Manz as Solomon’s weird, tap-dancing mom). Directors have been hailed as visionaries for less. In fact, if Gummo had subtitles and came from, say, the Netherlands or Spain, some of the same critics who shat all over it might have embraced it.

There’s also a hidden compassion in Gummo — the movie’s dirty little secret is that it’s not as coldly hip as it lets on. The notorious scene in which Solomon shoots the comatose old woman in the foot is actually rather ambiguous: this is their hapless attempt to wake her up. Another scene that drew critical fire — Korine’s cameo as a drunk guy who comes on to an encephalitic black dwarf after talking about how lonely he is — struck me as oddly moving. Can we just not deal with movies that don’t express emotions the same old way? Can’t we, for just 90 minutes, rise to the challenge of genuinely difficult art?

Your reaction to the people in Gummo says more about you than it does about them or Korine. If you recoil or laugh or scoff, you should ask yourself why. Perhaps the comatose old woman is Korine’s metaphor for the lazy, narrow-minded, unadventurous American audience that he hopes to wake up. Most critics have rewarded him with a kick in the ass, but they should be thanking him. Better he should make Lost in Space? I’m reminded of a great quote by Spike Lee: when an interviewer said that Spike’s use of different styles in the same movie isn’t what some people are used to, Lee retorted, “Most of the movies that people are used to suck anyway!” A sentiment with which, I think, Harmony Korine would heartily agree.

Explore posts in the same categories: art-house, cult

Leave a comment