Violet-capped Woodnymph – Hummingbird

The Violet-capped Woodnymph (Thalurania glaucopis) is a hummingbird found in eastern and southern Brazil (Bahia to Rio Grande do Sul), eastern Paraguay, far north-eastern Argentina (primarily Misiones Province) and possibly northern Uruguay. Its primary habitats are forests (primarily humid), dense woodland, forest edges, gardens and parks.

It is widespread and generally common, and therefore considered to be of Least Concern by BirdLife International (and consequently the IUCN).

Description

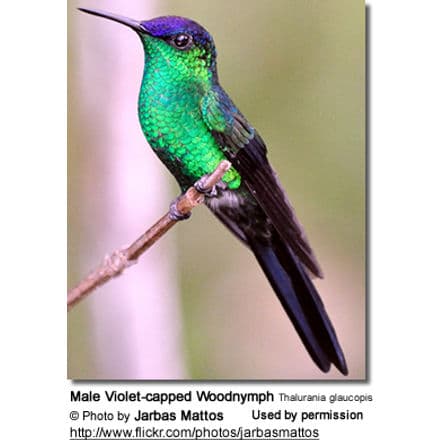

The Violet-capped Woodnymph measures about 4.4 inches (11.1 cm), including the tail. The bill is about 0.7 inches (1.8 cm) and the tongue about 1.6 inches (4 cm) long – both are well are adapted for feeding on deep, tubular-shaped flowers.

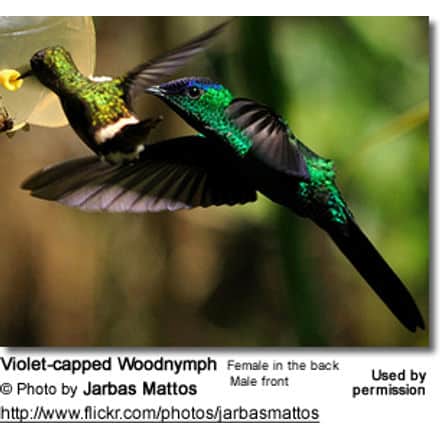

The male can be identified by his brilliant violet cap. The rest of his plumage is mostly glossy green, apart from the deeply forked dark blue tail.

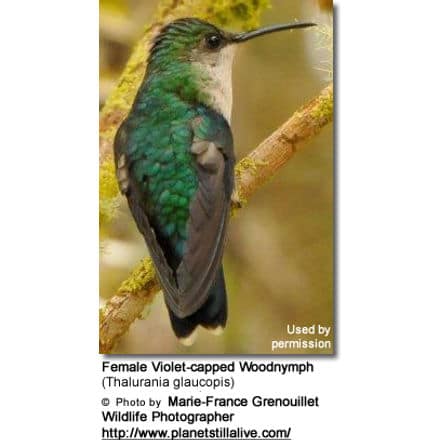

The female is not as flashy as the male. Her cap is greenish and her plumage below is whitish. There is a pale tip to her tail. Her tail is shorter than the male’s.

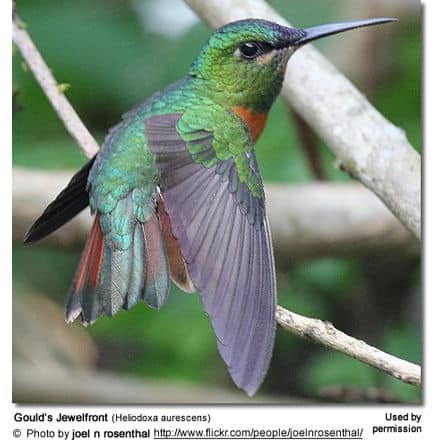

Similar Species

The male is pretty distinctive and could not easily be confused. However, the female resembles the Swallow-tailed Hummingbird, but can be told apart by her green cap, which is golden in the Swallow-tailed female.

Calls / Vocalizations

While feeding, they make sharp twitter or “chip’ sounds. The male’s song is a high-pitched piercing cheep tsew cheep tik-tik tsew.

Nesting / Breeding

Hummingbirds in general are solitary and neither live nor migrate in flocks; and there is no pair bond for this species – the male’s only involvement in the reproductive process is the actual mating with the female.

The male will separate from the female immediately after copulation. One male may mate with several females. In all likelihood, the female will also mate with several males. The males do not participate in choosing the nest location, building the nest or raising the chicks.

The Violet-capped Woodnymph is responsible for building the fairly large cup-shaped nest out of plant fibers woven together and green moss on the outside for camouflage in a protected location in a shrub, bush or tree – usually situated over a stream. She lines the nest with soft plant fibers, animal hair and feather down, and strengthens the structure with spider webbing and other sticky material, giving it an elastic quality to allow it to stretch to double its size as the chicks grow and need more room. The nest is typically found on a low, thin horizontal branch.

The average clutch consists of one white egg, which she incubates alone, while the male defends his territory and the flowers he feeds on. The young are born blind, immobile and without any down.

The female alone protects and feeds the chicks with regurgitated food (mostly partially-digested insects since nectar is an insufficient source of protein for the growing chicks). The female pushes the food down the chicks’ throats with her long bill directly into their stomachs.

As is the case with other hummingbird species, the chicks are brooded only the first week or two, and left alone even on cooler nights after about 12 days – probably due to the small nest size. The chicks leave the nest when they are about 20 days old.

Diet / Feeding

Even though Violet-capped Woodnymph eat some small insects, they primarily feed on nectar taken from a variety of brightly colored, scented small flowers of trees, herbs, shrubs and epiphytes. They favor heliconia and banana flowers; but may also visit some flowers that open during the night for bats.

They favor flowers with the highest sugar content (often red-colored and tubular-shaped) and seek out, and aggressively protect, those areas containing flowers with high energy nectar. They use their long, extendible, straw-like tongues to retrieve the nectar while hovering with their tails cocked upward as they are licking at the nectar up to 13 times per second. Sometimes they may be seen hanging on the flower while feeding.

Many native and cultivated plants on whose flowers these birds feed heavily rely on them for pollination. The mostly tubular-shaped flowers actually exclude most bees and butterflies from feeding on them and, subsequently, from pollinating the plants.

They may also visit local hummingbird feeders for some sugar water, or drink out of bird baths or water fountains where they will either hover and sip water as it runs over the edge; or they will perch on the edge and drink – like all the other birds; however, they only remain still for a short moment.

To a lesser extent, they feed on small spiders and insects – important sources of protein particularly needed during the breeding season to ensure the proper development of their young. Insects are often caught in flight (hawking); snatched off leaves or branches, or are taken from spider webs. A nesting female can capture up to 2,000 insects a day.

Males establish feeding territories, where they aggressively chase away other males as well as large insects – such as bumblebees and hawk moths – that want to feed in their territory. They use aerial flights and intimidating displays to defend their territories.

Hummingbird Metabolism and Survival and Flight Adaption – Interesting Information

With the exception of insects, hummingbirds have the highest metabolism rate of any animal on earth (high breathing rate, high heart rate, high body temperature).

Because of their “extreme” metabolism, the active hummingbirds require frequent feedings throughout the day – every ten to fifteen minutes and potentially visiting 1,000 flowers a day, lapping up nectar at the rate of 13 licks per second. They have to eat up to half of its body mass and drink roughly eight times its body mass each day. In preparation for an impending migration, hummingbirds may consume 3 up to 10 times their body weight in food – about 14,000 calories per kilogram – per day. (Humans consume, on average, 26 calories per kilogram per day). Before migration, hummingbirds will almost double their weight as they store up fat to serve as fuel and hence increasing their potential flying time.

The hummingbird has the largest heart in proportion to its body – and has the highest heartbeat rate. Their hearts, on average, pump about 1,200 times per minute in flight and 200 beats per minute at rest– making it the fastest beating heart of all animals – except for the pygmy shrew with a recorded heartbeat of up to 1511 times per minute. (A shrew is a small animal that resembles a mouse – it occurs in Asia.) The Violet-capped Woodnymph’s heartbeat (resting after a flight) has been recorded at 635 beats per minute and its daytime body temperature ranges from 105° to 108°F (40.5° to 42.2°C).

To conserve energy at night when they are not feeding, their bodies go into a state of torpor (temporary or semi-hibernation). During this time the hummingbird’s body temperature drops down dramatically from its daytime temperature of about 105° (40.5°C) to 19 °C (66 °F) and the heart rate slows down from about 200 (average daytime resting heart rate per minute)to 50 – 180 beats per minute. Hummingbirds may even stop breathing for periods of time. This allows hummingbirds to use up to 50 times less energy than they would need during their daytime activities. During this time, the hummingbirds cling to a branch and sit almost lifeless; sometimes their feet (which are known to be quite weak) will loosen their grasp enough to swing downwards and hummingbirds remain hanging upside down on the branch until the next morning or until they become alert when approached. People may even find semiconscious hummingbirds on branches, window sills or in garages, and when picked up, the warmth of hands is often enough to revive them, and they will buzz off in perfect health. This so-called “suspended animation” also enables hummingbirds to survive cold nights or any time that food might be scarce. At sunrise, the body temperature goes back up (which can take a few minutes up to an hour), and they will resume their normal activities – typically feeding before doing anything else. However, whether or not hummingbirds become torpid depends on their diet, health and type of activity they are engaged in (Long, 1997). For example, nesting female hummingbirds do not enter torpidity when incubating eggs as they need body heat to keep the eggs warm.

Unique flight abilities: Hummingbirds have skeletal and flight muscle adaptations that allow them to rotate their wings almost 180° – enabling them to fly forwards, backwards, up, down, sideways, even upside down. They can also remain still in space by moving their wings in a figure-eight pattern enabling them to remain stationary in the air – hovering in front of flowers as they feed on nectar. In fact, hummingbirds are more maneuverable than helicopters. Their normal flight speed is 30 mph (48 km/h), but they can reach 50 mph (80 km/h) during an escape or chase and even 63 mph (101 km/h) during a dive. Hummingbirds also spend a higher percentage of their lives flying than any other species. All of this is amazing particularly considering that these tiny birds weigh as little as a penny.

Hummingbirds are named for the audible low-pitched humming sound made in flight. This humming sound is made by the wings, and the sounds differ depending on how fast the hummingbird beats its wings. Each hummingbird species generates a different humming sound in flight.

Alternative (Global) Names

Chinese: ????? … Czech: kolib?ík fialovotemenný, Kolibrík mnohobarvý … Danish: Violetkronet Skovnymfe … Dutch: Violetkapbosnimf … Finnish: Sinineitokolibri … French: Dryade glaucope, Nymphe des bois du Brésil … Guarani: Mainumby … German: Blaukronennymphe, Veilchenkopfnymphe, Veilchenkopf-Nymphe … Italian: Driade capoviola, Ninfa dei boschi corona violetta … Japanese: sumireboushihachidori … Norwegian: Fiolettkronedryade … Polish: widlogonek fioletowoczelny, wid?ogonek fioletowoczelny … Portuguese: beija-flor-de-fronte-violeta, Tesoura-de-fronte-violeta … Russian: ????????????? ?????????, ?????????????? ?????? ????? … Slovak: dryáda ciapockatá, dryáda ?iapo?katá, Kolibrík fialkovotemenný … Spanish: Colibrí Hada de Coronilla Azul, Picaflor Corona Violacea, Picaflor corona violácea, Picaflor Frente Violacea, Picaflor verde de frente azul, Zafiro Capirotado … Swedish: Violettkronad skogsnymf

Hummingbird Resources

- Hummingbird Information

- Hummingbird Amazing Facts

- Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden

- Hummingbird Species

- Feeding Hummingbirds