Puerto Rican Nightjar

The Puerto Rican Nightjars (Caprimulgus noctitherus) is a very rare nightjar that was first described in 1888 from a previously misidentified skin found in Bayamón in the northern coastal valley near San Juan and sub-fossil bones from cave deposits. These specimens were considered to be the last remnants of a “prehistoric” bird and the Puerto Rican Nightjars was for all intends and purposes considered extinct at that time.

In 1911, Wetmore reported a sighting of this nightjar.

There were no further records of it until 1961, when the Puerto RIcan Nightjars was rediscovered by R. Cotte who spotted this bird in the Guánica forest in southwestern Puerto Rico (located on southern coast).

At the time, its numbers were considered to be tiny, and this nightjar’s conservation status was assessed as Critically Endangered. However, the results of more recent surveys suggest that species is more common than previously thought and the south-eastern population appears to be expanding its known range. Therefore, its status has been down listed to “Endangered.” This species is still at risk due to its limited and fragmented range and environmental degradation; and its numbers appear to be declining. It is now a legally protected species.

The Puerto Rican Nightjars is a member of the nightjar or goatsucker family, named such as they were once believed to drink a nanny’s goat’s milk during the night (the Latin word for goat-sucker or goat-milker is Caprimulgus). In the past, night-flying birds – such as the nightjars – were suspected of witchery.

Alternate (Global) Names:

Chinese: 波多黎各夜鹰 … Czech: lelek portorický … German: Puerto-Rico-Nachtschwalbe … Danish: Puerto Rico-natravn … Dutch: Puertoricaanse Whip-poorwill … Finnish: puertoriconkehrääjä … French: Engoulevent de Porto Rico … Italian: Succiacapre di Portorico … Japanese: puerutorikoyotaka … Norwegian: Puertoriconattravn … Polish: lelek czarnogardly … Slovak: lelek ciernohrdlý … Spanish: Chotacabras Portorriqueño … Swedish: Puerto Riconattskärra

Distribution / Range

Historically, the Puerto Rican Nightjars is believed to have occupied moist limestone and coastal forest in northern Puerto Rico, as well as the southern karst forests of the island, and may have ranged into the dry lower montane forests of La Cordillera Central (the Central Mountain range).

However, nowadays, this non-migratory bird is mostly restricted to three major areas in southwestern Puerto Rico, where it inhabits coastal dry and lower cordillera forests, namely:

- Susúa Forest and Maricao (a montane reserve located approximately 6 miles or 10 km to the northwest of Susúa) – most abundant in the southern regions of the Susúa Forest. Throughout the reserve, they are restricted to the drier forest on the steep slopes and ridges. Not found in the moist forest of Susúa, nor do they occur in gallery forest along rivers.

- Guayanilla HIlls – Peñuelas – Nightjars are abundant in this region of mature dry forest. Peñuelas is the only protected nightjar habitat in this portion of their range. They are not found in the moist forest and deep canyons.

- Guánica forest and adjacent private lands at Ensenada. Also Parguera Hills & Sierra Bermeja (east of Parguera). Most abundant in semi-deciduous and evergreen forests at elevations above 245 feet or 75 meters.

As part of conservation efforts, Guánica, Susúa and Maricao are now public lands designated as state forests. Guánica is a biosphere reserve (environmentally sensitive and nationally protected area). It comprises coastal areas with several mangrove cays and subtropical dry forest

In recent years, this species has been expanding its territory from Ponce through south-central Puerto Rico to Guayama province in the south-east.

Additional records exist from Parguera Hills and Sierra Bermeja, located on the southwestern tip of Puerto Rico (Vilella and Zwank 1993).

They are mostly found in closed canopy dry forest on limestone soils at elevations between 246 ft (75 m) up to 755 ft (230 m). These forests are composed of semi-deciduous hardwood trees with little or no ground vegetation, and abundant leaf litter on the ground.

At lower densities, they occur in dry, open, scrubby secondary growth, dry scrubland, open scrub-forest and thorny forest undergrowth. A few of them inhabit Eucalyptus (robusta) plantations.

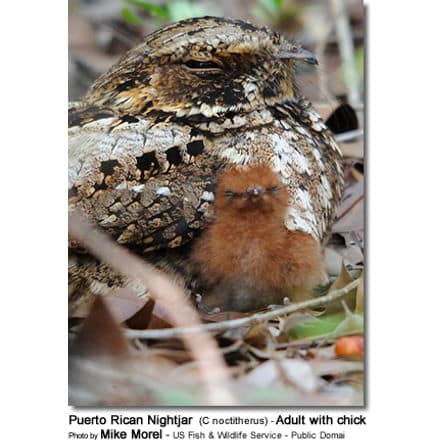

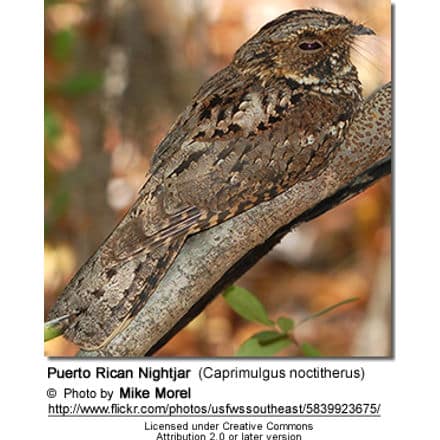

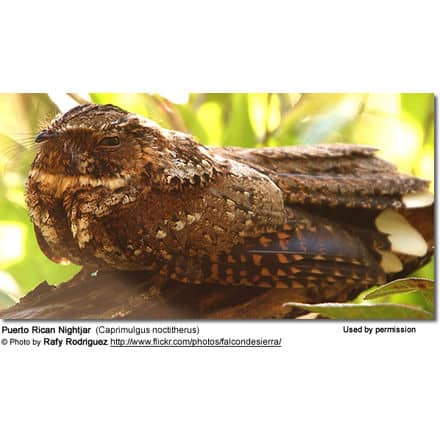

Their cryptic appearance blends perfectly into their habitat and they are very difficult to spot during the daytime, when they are usually hidden away sleeping. They are most easily detected at night when light from car headlights are reflected ruby-red from their eyes, as they are sitting on roads. However, their presence is most often made known by their loud calls given at dusk. They are generally seen alone (solitary).

Status

This species was previously believed to be extinct and this was mostly attributed to the introduction of the small Indian mongoose Herpestes auropunctatus (Vilella and Zwank 1993b), but also to early 20th century deforestation.

In more recent history, a proposed Wind Farm development consisting of 25 large turbines spread out over 725 acres situated in Karso del Sur IBA could have potentially wiped out 5% of the total breeding population due to the risk of collision with the turbines at night. Even though this project was originally approved, it was rejected by the government in 2010.

They nesting adults and young are at risk from being preyed on by mammals, predatory birds such as the Short-eared Owl and Pearly-eyed Thrasher, as well as reptiles. The very young may become victims to aggressive fire ants.

According to Vilella and Zwank (1993), the minimum population is estimated to consist of 1,400 – 2,000 individuals distributed among three separate areas of southwest Puerto Rico – based on 712 calling males found within 66% of the suitable habitat within its known range.

- Susúa-Maricao – 177 males

- Guayanilla-Peñuelas – 188 males

- Guánica-Bermeja – 347 males

Description

The Puerto Rico nightjar averages 8.6 inches (22 cm) in length – including its tail – and has a wing span of about 5.3 inches (135 mm).

The plumage is mottled grey, brown and black, resembling bark or leaves. The black throat is bordered by a white band. It has white markings on the outer-tail feathers. It has a relatively long bill surrounded by conspicuous rictal bristles (whiskers).

The female looks similar to the male, except she has a buff throat-band and outer-tail feathers.

Unlike other birds, they like to perch along a branch, rather than across it, which helps to conceal them during the day.

Like other nightjars, they have special physical adaptations that facilitate foraging at night and catching prey in mid-air, for example:

- The beak has evolved to be much wider than it is long, and it opens wide both – vertically as well as horizontally. The resulting big gaping mouth allows it to more easily scoop up insects in flight.

- Its large eyes are placed on each side of the head (laterally) – which significantly increases its visual field.

- A reflective membrane behind the retina (tapetum) enhances its vision at night by augmenting the light-gathering ability of its eyes.

- They also have forward-facing whiskers that may either help them funnel food into the mouth or protect the eyes.

Similar species:

- The Puerto Rico nightjar is smaller in size and is darker-plumaged than the related Whip-poor-will from the North American mainland.

- The Chuck-will’s-widow (a northern winter migrant) is larger with a more reddish plumage and less white in tail.

- The Antillean Nighthawk can be identified by its distinctive white wing patches.

Reproduction / Nesting

The Puerto Rican Nightjars peak breeding season is between April and June. However, nesting can commence as early as late February through early July. They are believed to be monogamous (only one mate for the duration of the breeding season).

The male establishes his territory and sings at night to keep rivals away and at the same time to attract a female.

The act of mating is preceded by several days of courtship (usually 2 to 7). The courtship ritual is usually performed close to the chosen nesting site and during the early evening hours (before 9 pm / 21:00 hours).

The pair will perch horizontally facing each other. The male will first perform his mating song and then drop his wings and spread his tail, while his body is vibrating in excitement. He will slowly walk towards the female – while both birds will emit soft, clucking sounds.

Nesting appears to be timed in such a way that the moon is more than half full at the time they are feeding their young – likely as the additional light during the night facilitates caring for the young and foraging for food.

Nightjars don’t actually construct a nest, as most other bird species do. They simply place the eggs on the ground on open soil covered with dead leaves. The nest is situated in a somewhat protected area — never in exposed areas or clearings. They are often reuse the same nest site.

After copulation, the female roosts for a few days close to the chosen nest site. The eggs are usually deposited directly on the ground. The clutch consists of 1 to 2 eggs (mostly two). The eggs are buffy brown with brownish purple spots (Kepler and Kepler 1973,

During the day, the incubation of the eggs is mostly undertaken by the female, while both parents share the incubation at night. The incubation period is about 18 to 20 days.

The hatchlings are covered in down and are capable of short-distance movements within 24 hours of hatching. They usually move apart shortly after hatching, maybe to make it more difficult for predators to spot them. The parents also shove them apart with their feet as they flush from the nest. The male usually stands guard and defends the nest and the young. He will hover in place near the nest with his body in a nearly vertical position and his tail spread showing off the white tail tips. The adults communicate with their young via soft clucking sounds to which the chicks respond.

Both parents feed the young regurgitated food (insects), and they continue to brood them until fledging. The young take their first flight when they are about 20 to 21 days old.

If conditions are favorable, the female may lay a second clutch close to the first and while she is incubating the new set of eggs, the male continues to care for the young from first brood.

They have developed several behavioral adaptations to minimize predation:

- Their nocturnal (night) lifestyle reduces the likelihood of being detected by daytime predators. During the daytime, they typically sleep on the ground where they are perfectly camouflaged by their “earthy” colored plumage. They almost always change their roost sites on a daily basis.

- When nesting, they sit quietly on the eggs, minimizing any movements that could get them detected.

- If an intruder does get close to the nest, the parents may try to lead them away by first flushing off the nest and when landing feigning injury as they lead the potential thread away from the nest. While the parent performs this distraction display, the young may scatter and freeze.

- The parent who is not incubating the eggs or brooding the young will roost away from the nesting area.

- They may also move the eggs or young to prevent them from being preyed upon.

Nightjars avoid voicing when they hear the calls made by predatory nocturnal animals, such as owls.

The Feeding Habits of Nightjars / Nighthawks

Calls / Vocalizations

Even though Male Puerto Rican nightjars sing throughout the year, they are most vocal during the breeding season between February and July, as they are singing to attract females. Their songs consist of continuously whistled whip whip whip. Usually its song consists of 2-15 notes, but may be maintained for up to 160 notes.