Whinchat Saxicola rubetra Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (43)

- Monotypic

Text last updated March 9, 2016

Sign in to see your badges

Species names in all available languages

| Language | Common name |

|---|---|

| Afrikaans | Europese Bontrokkie |

| Albanian | Ҫeku vetullbardhë |

| Arabic | قليعي أحمر |

| Armenian | Մարգագետնային չքչքան |

| Asturian | Charchar nortiegu |

| Azerbaijani | Çəmən çəkçəkisi |

| Basque | Pitxartxar nabarra |

| Bulgarian | Ръждивогушо ливадарче |

| Catalan | bitxac rogenc |

| Croatian | smeđoglavi batić |

| Czech | bramborníček hnědý |

| Danish | Bynkefugl |

| Dutch | Paapje |

| English | Whinchat |

| English (United States) | Whinchat |

| Faroese | Reyðstólpa |

| Finnish | pensastasku |

| French | Tarier des prés |

| French (France) | Tarier des prés |

| Galician | Chasco norteño |

| German | Braunkehlchen |

| Greek | Καστανολαίμης |

| Hebrew | דוחל חום-גרון |

| Hungarian | Rozsdás csuk |

| Icelandic | Vallskvetta |

| Italian | Stiaccino |

| Japanese | マミジロノビタキ |

| Latvian | Lukstu čakstīte |

| Lithuanian | Paprastoji kiauliukė |

| Norwegian | buskskvett |

| Persian | چک بوته ای |

| Polish | pokląskwa |

| Portuguese (Portugal) | Cartaxo-nortenho |

| Romanian | Mărăcinar mare |

| Russian | Луговой чекан |

| Serbian | Obična travarka |

| Slovak | pŕhľaviar červenkastý |

| Slovenian | Repaljščica |

| Spanish | Tarabilla Norteña |

| Spanish (Spain) | Tarabilla norteña |

| Swedish | buskskvätta |

| Turkish | Çayır Taşkuşu |

| Ukrainian | Трав’янка лучна |

Saxicola rubetra (Linnaeus, 1758)

Definitions

- SAXICOLA

- saxicola

- rubetra

- Rubetra

The Key to Scientific Names

Legend Overview

Field Identification

12–14 cm; 13–26 g. Breeding male has buff-streaked blackish face and crown, with prominent white supercilium, narrow white line from chin to neck side, buff mantle to rump with blackish streaks and spots, blackish wings with buff edgings and white alula, short black tail with white outer bases; rufous-ochre below, shading to white on belly; bill and legs black. Non-breeding male buffier on head, with dark stippling on breast. Female is like male but less distinctly marked, with buffy supercilium and brown face, less white in wing and tail. Juvenile is like female, with dark mottling and scaling on breast and flanks.

Systematics History

Subspecies

Hybridization

Hybrid Records and Media Contributed to eBird

-

Common Redstart x Whinchat (hybrid) Phoenicurus phoenicurus x Saxicola rubetra

Distribution

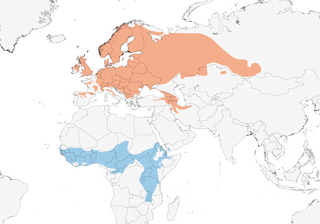

Europe E to W Siberia, E (probably also NW (1) ) Turkey, Caucasus and NW Iran; non-breeding Africa.

Habitat

Breeds in wet meadows, pastures, bogs, upland grassland, bracken-covered hillsides, heath, dry or wet open scrub and fringes of reedbeds, general requirement being for scattered shrubs, bushes, trees or man-made perches for songposts and foraging vantages, and low herb cover and bare ground in which to forage (shrubs and herb layer also needed for nesting). Precise factors in ecological separation from widely sympatric S. torquatus in W Palearctic not quantified, but tends to occupy wetter, grassier, more open terrain with less woody-stemmed vegetation; yet also more flexible, occurring in Finland and Russia in glades, clearings and burns inside forest, and sometimes perching high on dead tree or flagpole. In Poland, favours abandoned cropfields with well-developed layer of dried perennials (Tanacetum vulgare, Artemisia vulgaris, Solidago) from previous year; probability of occupation was 50% in fields of c. 1·8 ha, rising to 100% in fields larger than 13 ha, with density of territories negatively correlated with size of field, and single males inhabiting smallest fields. Reaches 500 m in Britain, 1800 m (rarely 2200 m) in Switzerland, 2230 m in Armenia. In parts of range, some evidence that Great Grey Shrike (Lanius excubitor) inhibits settlement of otherwise suitable habitat. In African winter quarters occupies moist open areas with low perches; open or lightly bushed grassland, grassy marsh (avoided in Ivory Coast), forest edge and clearings, degraded savanna, gardens, fallow and harvested fields, bare hilltops; home ranges 0·4 ha and contain 3–12 bare patches of ground used for foraging from low perch. In Sierra Leone occasionally in small mangroves; in Uganda in tall grassland up to 2300m.

Movement

Migratory, most wintering in tropical Africa; loose aggregations form during migration. Leaves European breeding grounds late Aug to Sept (juveniles generally earlier than adults), those from NW & C Europe moving SW through W France, W Iberia and W Mediterranean , passing through Spain and N Africa late Aug to Nov/Dec (main passage mid-Sept to end Oct) and through N tropics late Sept to mid-Nov; paucity of ringing recoveries in autumn from N Africa suggests that many make single flight across Sahara from S Europe. E populations migrate through Middle East; main passage Israel mid-Sept to mid-Oct, Jordan mid-Sept to early Oct, Bahrain (scarce) Sept–Oct; passage in Africa generally light, suggesting broad-front movement and often in a single step; rapid passage in Eritrea late Aug to mid-Sept. Main arrival in winter quarters Oct–Nov, but in extreme S areas (Zambia, Malawi) only late Oct to Dec; ringing recoveries from Tunisia and Libya and from Togo and Nigeria suggest origin in C Europe; birds on passage in Egypt and Ethiopia and wintering in E & S of African range presumably originate in Russia. High site fidelity detected at a winter locality in Nigeria: across two years, 54% of birds returned to and all returning birds reoccupied the territories they used in the previous winter (2). Spring departure mainly Feb in Zambia, otherwise mid-Mar to early Apr, and in W Africa mainly early Apr; passage in Senegal mid-Mar to early May, in Ethiopia mid-Apr, but many migrants appear to undertake direct long-haul journey to reach at least N Africa, where passage strong between late Mar and mid-May; main spring passage Israel Apr and first half May, Jordan mid-Apr to early May, UAE second half Mar to end Apr, Bahrain late Mar to mid-May (mostly Apr). Arrival on breeding grounds mid-Apr in S, late Apr or early May in C & NW Europe, but many N parts of range not occupied until late May. In C Nigeria birds leave their winter territories throughout Apr, with males departing on average 8 days earlier than females; since departure dates show a discrepancy of at least 2 weeks with arrival dates in S Europe, and given that birds depart their winter territories with a predicted mass of c. 17 g, considerably less than the c. 24 g required for the average Whinchat to cross the Sahara directly, it seems that they possibly stage further north, closer to the southern limit of the Sahara (3).

Diet and Foraging

Mainly invertebrates, supplemented in autumn by fruit or seeds. Animal food includes adult and larval beetles of at least twelve families, adult and larval lepidopterans of at least three families, flies of at least eight families, sawflies, ants and bees, mayflies, dragonflies, grasshoppers, earwigs, bugs, caddis flies, spiders, woodlice, centipedes, millipedes, snails and earthworms. In three small samples of stomachs from Russia and Ukraine, spring, summer and autumn, beetles and ants predominated by number, with following data from Sept: 28% beetles, 25% ants, 17% bugs, 3% grasshoppers, 8% unidentified insects, and 19% Solanaceae seeds. In other samples beetles sometimes exclusively taken, while only other reported plant food is blackberry (Rubus fruticosus), taken in autumn prior to migration. Young at five Russian nests fed mainly with mid-sized prey, initially soft-bodied animals such as small spiders and sawfly larvae. Of 709 prey items brought to large nestlings in Poland, 25% were adult and 16% larval lepidopterans and sawflies, 15% craneflies, 13% grasshoppers, 10% spiders, 6% flies, 11% unidentified insects, and less than 5% snails, Odonata, beetles and wasps. In Switzerland, elevational influence of proportions of animal food fed to nestlings revealed by study of 15 nests at 900–1000 m and five nests at 1400–1500 m, respectively yielding 27% and 60% hymenopterans, 27% and 2% beetles, 21% and 12% flies, 14% and 18% lepidopterans, 3% and 4% grasshoppers, 2% and 0% bugs, 3% and 2% snails, 2% and 2% spiders, 1% and 0% earthworms, but with complete avoidance of abundant moths Odetia atrata, scorpionflies, staphylinid and chrysomelid beetles and dungflies. An individual recorded taking a young small lizard (Lacerta vivipara) in France (4). Forages from perch, taking prey from ground, less frequently from vegetation or in flight; aerial sallying may be common in winter quarters, where tall grass often covers and hides open ground. Sometimes establishes temporary territory on wintering grounds.

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Song, by male only (often at night in spring; rarely in winter quarters), a series of loud, fast and abrupt short phrases (1–1·5 seconds long), each a buoyant jumble of scratchy rattles, hoarse rasps, clear whistling and (often excellent) snatches of mimicry; in courtship song becomes softer “ziwüziwü”, and in male-male confrontations a rapid scratchy rattling. Calls include whistled “fiu” or “djü” for alarm-contact, harsh “tec tec” in stronger warning, and a combination of both, e.g. “hüü-tuc-tuc”, in alarm near nest.

Breeding

Mid-Apr to early Aug in NW Europe. Territory less than 1 ha, average 0·43 ha in Netherlands, at least 0·75 ha in W Germany; site-fidelity among adults high (of 54 breeding males, 47% returned to same area after one year, 15% for two years and 4% for three years, and almost half of all these reoccupied same territory). Nest a cup of grass stems, leaves and moss, lined with fine stems and hair, placed in low bush or tussock. Eggs 4–7, pale blue with fine reddish-brown speckling; incubation period 12–13 days; nestling period 12–13 days, although young not capable of flight until 17–19 days; post-fledging dependence 15–18 days. In Britain, hatching success 72% and fledging success 94%, giving 86·5% overall breeding success. Causes of mortality among ringed individuals in NW Europe are domestic predator 10%, human-related (accidental) 24%, human-related (deliberate) 55%, other 11%. Age of first breeding 1 year.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened (Least Concern). European population in mid-1990s estimated at 2,441,507–3,044,673 pairs (highest numbers in Belarus, Latvia and Finland), with additional 100,000–1,000,000 pairs in Russia and 500–5000 pairs in Turkey; at that time Spain estimated to hold 15,000–20,000 pairs, although more recently minimum population put at 2775 pairs. By 2000 total European population (including European Russia and Turkey) revised to 5,400,000–10,000,000 pairs, and considered generally stable. Densities in optimal habitat on unimproved farmland, abandoned farmland and high alpine meadows 1 pair/ha (100 pairs/km²), but commonly less, e.g. 0·8 and 0·65 pairs/ha in lower alpine meadows and falling to 0·06–0·12 pairs/ha in S Wales and 0·03–0·04 pairs/ha in SW Scotland. Since 1955, densities in W & C Europe have been declining with agricultural intensification, and populations in Britain, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany have fallen by 50%, although lessening or levelling c. 1980 owing to reductions in rates of farming intensification; but only 5–7 pairs left in Belgium in 1998. In some areas (e.g. SW Germany), key issue is date of mowing; and in France intensive farming in Auvergne directly caused loss of 72% of first broods through early harvesting, and 63% of second broods. Rate of deliberate capture in winter quarters of birds ringed in NW Europe remarkably high, and may be a factor in declines. Nevertheless, a study of colour-marked birds overwintering at six sites in Nigeria found very high overwinter survival, implying that population declines may not be due to circumstances in the winter quarters (5). In Africa, common to abundant visitor in guinea savanna and savanna-forest mosaic, less common in soudan belt; frequent to uncommon E of L Victoria and S of c. 3º S; density in N DRCongo 0·8 birds/ha.

- Year-round

- Migration

- Breeding

- Non-Breeding