- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

Few birds match the pluck and charm of the tiny but mighty Anna’s Hummingbird.

While many bird species are currently in decline, the Anna’s Hummingbird has adapted to life in urban areas across western North America and expands its range each year.

In fact, if you live in the urban west, you’ve probably got one in your yard right now – I can hear my resident male singing as we speak!

Anna’s Hummingbirds are unusual among North American hummingbirds for their fairly large size, red iridescent crowns, spectacular dive displays, and long, intricate songs.

But how do you identify one? Keep reading, and I’ll break down how to identify, observe, and appreciate the glory that is the Anna’s Hummingbird.

Taxonomy of Anna’s Hummingbird

Anna’s Hummingbirds are members of the order Apodiformes, which also includes the swifts and treeswifts. Contrary to the order name, which means “no feet” in Latin, hummingbirds do, in fact, have feet – albeit very small ones.

The hummingbird family, Trochilidae, is found only in the Americas and is extremely diverse, with over 350 recognized species.

Anna’s Hummingbird is in the genus Calypte, which only includes two species: the Anna’s, and its cousin, the Costa’s Hummingbird. Both are distinctive for their “helmets,” or iridescent head and throat feathers.

Its common name came about when French naturalist René Primevère Lesson discovered the Anna’s Hummingbird on his travels in the 1800’s and named it for Anna Masséna, who was the Duchess of Rivoli.

Taxonomy At a Glance

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Apodiformes

- Family: Trochilidae

- Genus: Calypte

- Species: C. anna

How to Identify Anna’s Hummingbird

Anna’s Hummingbirds are relatively large for North American hummingbirds, with robust bodies (3.5 to 4 inches total length) and large heads.

Compared to other hummingbirds, they have medium-length, straight bills, and longer tails. When perched, they hold their tails in line with their bodies, and their tail feathers extend well past the wingtips.

The time of year can also be helpful for identification. In many regions, Anna’s Hummingbirds are the only hummingbirds present in winter.

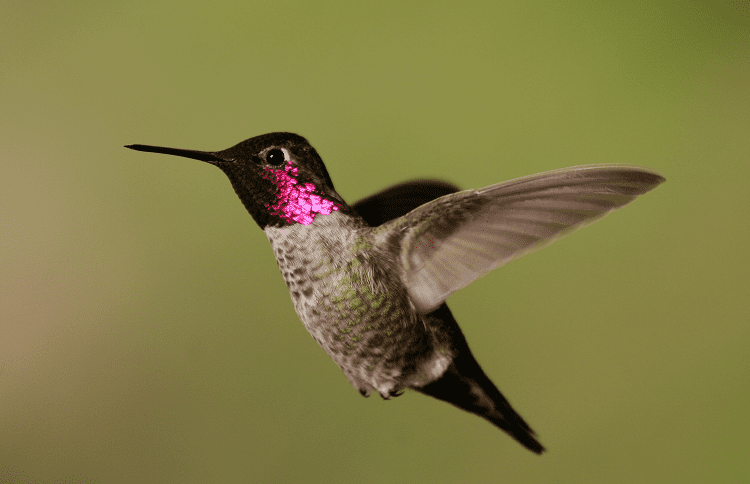

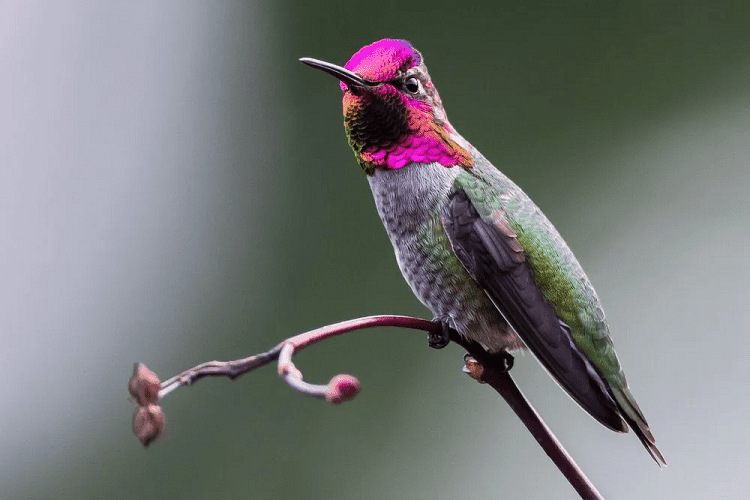

Adult Males

Male Anna’s Hummingbirds are fairly easy to identify. They are the only male hummingbirds in North America with red crowns; that is, the feathers on top of their heads are bright, rosy red. They also sport long red gorgets, or, throats. The older the bird, the longer the corners, or sides of the gorget, will be.

The feathers of both the crown and gorget are iridescent, which is also unusual for North American hummingbirds, and the color will appear redder than the more purplish hues of the similar Costa’s Hummingbird. As the feathers become worn with sun damage and age, the rosy red color will take on a more orange or coppery hue.

When the birds are not angled to face the sun, their heads will appear dark gray and drab. This is due to the structural coloration of the iridescent feathers, which rely on light to produce their colors, much like a prism. The backs of male Anna’s Hummingbirds are also iridescent, and are a vivid green with hints of metallic blue when in direct sun.

While the crown and gorget are the most distinguishing features, there are a few other markings you can check for. Male Anna’s Hummingbirds have a white ring around their eyes. They also have pale edges on their upper breast feathers, which gives them a scaly appearance.

If you still aren’t sure that you have a male Anna’s, check the tail. The underside of the feathers will be edged with gray, and the outermost tail feathers are narrow and rounded at the tip.

Adult Females

Female Anna’s Hummingbirds are a little trickier to identify. Like all female hummingbirds, they are drabber than the males and are typically iridescent green on their backs and pale mottled gray on their undersides. These earth-tones allow them to stay camouflaged on the nest while they incubate and tend their young.

Compared to other female hummingbirds, they have relatively broad tails, the outermost tail feathers of which are banded in dark grayish green or black and tipped with white.

Also, look for the white crescent above their eyes and the small, red gorget patch in the middle of their throats which is unusual among female hummingbirds. This throat patch varies from a few gray feathers with a hint of bronze to a bright red iridescent diamond. As with the males, the older females have larger throat patches.

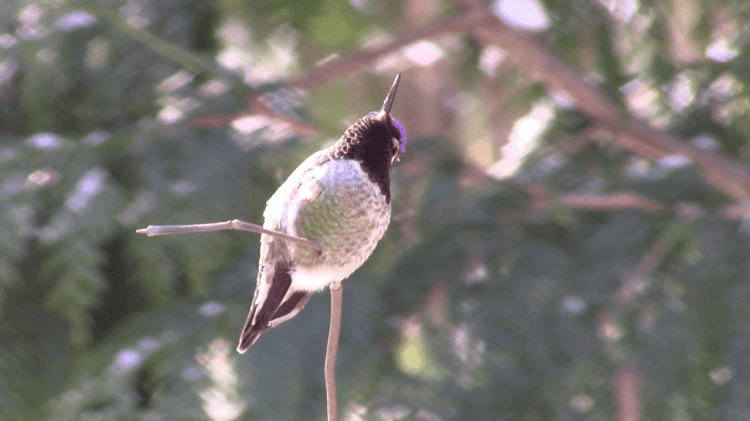

Immature Birds

If you have a juvenile bird, typically encountered between June and September, pay close attention to the gorget.

Immature female Anna’s Hummingbirds look similar to adult females but do not have the extensive throat patch. On young birds, it may only consist of a few grayish feathers and often lacks iridescence.

Immature males look a lot like adult females but will have a more defined central throat marking with larger iridescent feathers visible. Immature males also have paler feather edges on their breasts, giving them a scaly look.

Note: Anna’s Hummingbird occasionally hybridizes with the closely related Costa’s Hummingbird. Hybrids often look like a Costa’s Hummingbird but vocalize like an Anna’s.

Anna’s Hummingbird Vocalizations and Sounds

One of the best ways to identify Anna’s Hummingbirds is to listen for their characteristic sounds.

Song

Male Anna’s Hummingbirds sing a repeated 10-second-long series of scratchy, buzzy, metallic notes with a few more melodic whistles thrown in that kind of sounds like a squeaky wheel.

It might not seem like a song to most, but it is actually fairly long and complicated for a hummingbird, which is not a true songbird! Listen for this song year-round, and look for a singing male perched 6 feet or more off the ground.

Calls

When confronting intruders, males will give an unmistakable “zeega, zeega, zeega!” battle cry.

Both males and females issue a “chik” call, usually singly but sometimes doubly. When agitated, they may issue a rapid series of calls.

Dive Noise

Male Anna’s Hummingbirds also produce a loud squeak with their tail feathers as part of their dive display that sounds like a sneaker scuffing on a gym floor.

Where Does Anna’s Hummingbird Live: Habitat

Range

Historically, Anna’s Hummingbirds were only found in the chapparal biome of southern coastal California and northern Baja California. The introduction of exotic garden plants, eucalyptus trees, irrigation, and feeders allowed them to rapidly colonize the west in the mid-19th century.

Today, Anna’s Hummingbirds are found throughout the west, as far north as British Columbia, and as far east as Texas. Their range is still expanding, and vagrant birds turn up all over the United States and Canada each year.

Anna’s Hummingbirds are found farther north than any other hummingbird species on a year-round basis, making use of feeders and their ability to go into torpor, a form of suspended animation similar to hibernation, when conditions become too harsh.

Habitat

Anna’s Hummingbirds are very adaptable and are now common in urban areas like parks, gardens, and backyards with feeders. They also frequent eucalyptus groves, orchards, and riverside woodlands. Where they have colonized the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts, they do not stray too far from water and food sources.

Anna’s Hummingbirds are also found in wilder areas similar to their original range, including: inland chaparral, coastal scrub, riparian woodlands, oak savannah, and evergreen-oak woodland. They prefer lower elevations and are most common between sea level and 5,700 feet.

Anna’s Hummingbird Migration

Unlike most other hummingbirds, Anna’s Hummingbirds do not migrate in the conventional sense. Depending on conditions, they may migrate short distances to find better food sources or a milder climate.

This typically involves relocating from lowlands to the mountains to follow the wildflower blooming seasons, moving from east to west in the deserts, or flying a short distance south from extreme northern areas to a warmer part of their range in winter.

Anna’s Hummingbird Diet and Feeding

Nectar

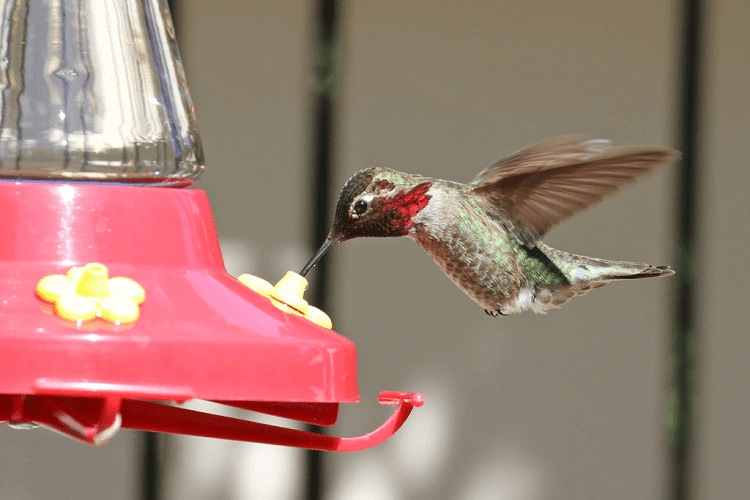

Anna’s Hummingbirds feed primarily on nectar from a wide variety of flowers (or the sugar water substitute offered in feeders).

They approach a food source and either perch or hover before it, using their long, extendable tongues to pull in the nectar through capillary action. They feed every 10 to 15 minutes and can visit up to 2,000 flowers per day (or, for backyard birds, one feeder repeatedly).

Preferred food plants are those found in their historic chaparral range, such as: fuchsia-flowered gooseberry, manzanita, wooly blue curls, chaparral currant, California fuchsia, pitcher sage, red bush-penstemon, bush monkeyflower, and western columbine.

They have developed preferences for certain exotic plants over the years as well. These include: aloes, eucalyptus, bottlebrush, citrus, and tree tobacco.

Insects and Spiders

Anna’s Hummingbirds also eat more insects than any other North American hummingbird, especially during winter and nesting season. A single female Anna’s can eat up to 2,000 insects a day when feeding young!

They are known to take gnats, midges, leaf hoppers, whiteflies, thrips, small caterpillars, fruit flies, insect eggs, spiders, and spider eggs and young.

Insects are most often snatched right out of the air – if you notice a hummingbird flying erratically in bizarre zig zags in an open area, they are likely hunting a swarm of winged insects in a behavior called hawking!

Insects are also taken from the undersides of leaves, out of flowers, along stream banks, from leaf litter, from within crevices and bark, and even plucked right out of spiderwebs.

Anna’s Hummingbirds have also been observed feeding on tree sap oozing from sapsucker wells (as well as the insects stuck in it). They will also consume sand and ashes for the supplemental minerals.

Feeders

If you choose to feed hummingbirds, use a mixture of white table sugar and water in a ratio of 1-part sugar to 4-parts water. This concentration most closely mimics the nectar naturally found in flowers. Never use honey, other sugars, or red dye.

If you store the mixture, boil the water first. Be sure to change the sugar water and clean the feeder frequently to avoid the growth of bacteria and fungi than can be deadly to hummingbirds.

Anna’s Hummingbird Breeding

The Anna’s Hummingbird breeding season begins in late December and extends well into summer. Males and females have completely separate roles in breeding, with females building nests and rearing young solo while males rigorously defend territories against rivals and ceaselessly perform courtship displays.

Male Dive Display

Breeding begins with an elaborate courtship display known as a dive display performed by the male, who defends a feeding territory year-round to increase his likelihood of interacting with females.

When a female, who has been quietly scouting nest sites, ventures into a male’s territory to feed, the resident male will approach her – hovering over her singing a series of buzzy notes.

He will then shoot straight up into the air, rising 65 to 130 feet in a matter of 7 to 8 seconds. At the apex, he will orient himself, so his iridescent gorget faces the sun, flashing her with his intense color. Then he will plummet back to his starting point in no more than two seconds, emitting a loud squeak or dive noise with his outer tail feathers as he passes the perched female.

He will often repeat the sequence many times and, on occasion, uses the dive display to intimidate rival males, other birds, and even people. The loud dive noises of the male Anna’s Hummingbird sound similar to a sneaker scuffing on a gym floor and are a sure sign that the breeding season has begun!

Male Shuttle Display

If the female deems the male worthy, she will lead him back to her chosen nest site. There, he will often perform a shuttle display, in which he hovers back and forth above her like a pendulum, pointing his bill directly at her, raising his gorget feathers, fanning his tail, and vocalizing rapidly.

The female watches this display, orienting herself on her perch to face him as he zooms back and forth. If she approves, she will then allow him to mate with her.

Anna’s Hummingbirds do not form pair bonds, and both males and females will likely mate with several partners over the course of a single season.

Anna’s Hummingbird Nesting

Female Anna’s Hummingbirds handle all nesting responsibilities alone with no assistance from the male. They select and defend territories with good nesting sites.

A female first selects a suitable nest site, which is typically a horizontal branch 4 to 25 feet above the ground that is close to a reliable nectar source. Trees and shrubs, particularly oaks, sycamores, and eucalyptus, are the most common nest sites, but on occasion, vines, poison oak, and manmade structures like wire cables and eaves have been utilized.

The female Anna’s then begins constructing the nest, which usually takes 3 to 14 days (rarely up to a month) depending on the individual, time of year, and availability of materials. She starts with the bottom of the cup, then sits in the nest and builds it around her. Females search high and low for nest-making components and will even steal them from other nests.

The cup lining is built out of soft materials, such as white plant fibers, animal hair, plant down (like cattail and thistle fluff), fine stems, leaves, lint, carpet fibers, and feathers, and is held together with silk from spiderwebs and insect cocoons. The silk makes the nest elastic and allows it to stretch as the nestlings grow.

The outside of the nest is then camouflaged with lichens, plant debris, moss, leaves, and sometimes artificial materials like cigarette paper and paint chips to disguise the lighter-colored inner cup. Females may finish this part while incubating eggs.

Anna’s Hummingbird Eggs

Anna’s Hummingbirds typically lay two eggs per clutch. On rare occasions, they will lay only one or will lay up to three. Eggs are laid every two days, so nestlings will always be at least two days apart in age.

The eggs are small (0.6 inches by 0.3 inches), white, and elliptical. They are smooth, more matte than glossy, and feature no speckles or markings.

The female incubates the eggs for 16 to 17 days before the young hatch.

Anna’s Hummingbird Nestlings

Young Anna’s Hummingbirds are altricial, meaning they are helpless and mostly naked with eyes closed when they first emerge. The chicks have black skin, sparse light gray down, short bills, and bright yellow mouths.

The female continues to brood them for an additional 12 days after they hatch as they cannot regulate their own body temperatures.

The female Anna’s Hummingbird must then search for food nonstop to nourish the rapidly growing chicks. She feeds them by sticking her bill deep in their mouths and regurgitating nectar mixed with protein-rich insects.

At 5 days old, the chicks’ eyes open up. By the end of their first week, their first pin feathers have emerged. They fledge the nest at 20 to 26 days old.

A female Anna’s Hummingbird will raise 2 to 3 broods in a single season. They are diligent mothers and, on occasion, starve to death, brooding their young during inclement weather.

Anna’s Hummingbird Population

The Anna’s Hummingbird is the most common hummingbird on the west coast. They are numerous throughout their current range, and their range continues to expand each year.

According to Partners in Flight, they have an estimated global breeding population of 9.6 million birds. The North American Breeding Bird Survey shows that their numbers have increased by over 2% per year between 1966 and 2019. This is likely due to their adaptability and range expansion.

Is Anna’s Hummingbird Endangered?

The Anna’s Hummingbird is not endangered. In fact, it is thriving, and its population is increasing each year.

The Anna’s Hummingbird has an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List ranking of Least Concern and is not currently at immediate risk for extinction.

Anna’s Hummingbird Habits

Foraging

Anna’s Hummingbirds are often seen flying from flower-to-flower drinking nectar or visiting backyard feeders. Often, they will visit feeders and flower patches in a predictable order each day in what is known as trap-lining.

They usually hover before a food source but will also perch. Unlike the tail-wagging Black-chinned and Costa’s Hummingbirds, Anna’s hold their tails still while hovering.

Territorial Defense

Adult male Anna’s Hummingbirds make themselves known by singing a series of metallic, buzzy notes with a few melodic whistles mixed in to proclaim their feeding territory and are quite entertaining to watch.

Males will perch about 6 feet or more off the ground on a bare tree branch or powerline near their nectar source and sing to ward off rival males and attract females.

If another male approaches, he will sway back and forth on his perch, flaring his gorget and raising his crown, all while singing and chattering harshly. He will also move his head from side to side to flash his iridescent feathers at the intruder as a warning.

If the interloper does not take the hint and leave, he will hover in front of him, gorget flared, and sing and chatter intensely. The encounter will then escalate to a chase accompanied by the aggravated “zeega zeega zeega!” war cry and, on occasion, a battle that can take both birds to the ground.

A male Anna’s Hummingbird will defend his territory year-round. Due to this taxing lifestyle, in which nutrition is neglected in favor of territorial behaviors, male hummingbirds do not live as long as females.

Female Anna’s Hummingbirds will defend their nesting territories as well. Predators, rival females, and sometimes humans will be run off with dives and chittering calls if they get too close to the nest.

Anna’s Hummingbird Predators

Adult Anna’s Hummingbirds are small, fast, and agile. This keeps them safe from many predators, but not all of them.

By far, the greatest threat to these birds are outdoor domestic cats. Cats will stake out feeders or pounce on hummingbirds while they are feeding on flowers low to the ground. Cats kill more Anna’s Hummingbirds than any other animal.

Predatory birds like American Kestrels, Sharp-shinned Hawks, Merlins, Greater Roadrunners, Western Scrub-Jays, and Loggerhead Shrikes have also been known to feed on Anna’s Hummingbirds. Even some opportunistic songbirds, like Curve-billed Thrashers, will take one if they get the chance.

Owls and snakes may capture hummingbirds at night while they are sleeping or in torpor.

More unusual predators include: large praying mantids, large orb-weaver spiders, South American bird-eating tarantulas, frogs, fish, and lizards.

Eggs and young are eaten by a wide variety of predators, including: snakes, lizards, bats, birds (like corvids, grackles, and toucans), squirrels, chipmunks, and rats.

Other causes of death include: window collisions, infections from drinking bad feeder mix, and, rarely, getting bees impaled on their bills, which causes them to starve to death.

Anna’s Hummingbird Lifespan

Anna’s Hummingbirds live about 8 years. Currently, the oldest banded bird lived to be at least 8 years and 2 months old.

On average, female hummingbirds live longer than males due to their camouflaged coloration and less physically demanding lifestyles.

Like all hummingbirds, they have high mortality rates early in life. Most Anna’s Hummingbirds do not survive past their first year.

FAQs

Answer: Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are smaller and less robust birds. Male Ruby-throats will have a black mask and a green crown, while male Anna’s have white eye rings and red crowns. Female Ruby-throats lack the red throat patch and do not have a thin white strip over their eyes like female Anna’s do.

In addition, the range of these two species does not overlap. If you are in North America, Anna’s Hummingbirds dominate the West Coast, while Ruby-throated Hummingbirds live on the East Coast. If you are in Mexico or South America, you are most likely to encounter a Ruby-throated Hummingbird, as Anna’s only occur in northwestern Mexico.

While vagrant rarities occur, you are far less likely to see a bird outside of its natural range. This should help narrow down the identity.

Answer: Much like many other birds, male Anna’s Hummingbirds sing for the dual purposes of announcing their territory to rival males and attracting females. Since they defend a food resource, like a flower patch or feeder, rather than a breeding territory as many birds do, they sing year-round.

Answer: Anna’s Hummingbirds are remarkably easy to attract. If you live in their natural range, simply set out a hummingbird feeder. Use a mixture of 1-part white table sugar to 4 parts water. Don’t use honey, other sugars, or red dye, and be sure to change the mixture regularly, especially in hot weather.

Usually, hummingbirds will notice your feeder within days and will become frequent visitors. A male may even stake out your feeder and begin guarding it! This will allow you to view their unique behaviors up close.

You can also plant a garden of their favorite nectar plants, like sage, penstemon, aloes, eucalyptus, bottlebrush, citrus, and currant.

Hummingbirds love to bathe, so a bird bath will also attract them to your yard.

Research Citations

Books

- Alderfer, J., et al. (2006). Complete Birds of North America (2nd Edition). National Geographic Society.

- Baicich, P.J. & Harrison, C.J.O. (2005). Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (2nd Edition). Princeton University Press.

- Kaufman, K. (1996). Lives of North American Birds (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Sibley, D.A. (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Williamson, S.L. (2001). Hummingbirds of North America (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Online

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Annas_Hummingbird/overview

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: