Birdfinding.info ⇒ Common to locally abundant from late May to mid-July in its breeding areas on the northern Great Plains—especially from Alberta to North Dakota. Briefly common in spring migration (late April to mid-May) in the Southwest. Much more widespread across North America from July to September, but numerous mainly in reservoirs of the Great Basin and Great Plains. In winter, common along the Pacific coast of South America from Guayaquil to central Chile, in the pampas of Argentina, and on Andean lakes from southeastern Peru to northwestern Argentina.

Wilson’s Phalarope

Phalaropus tricolor

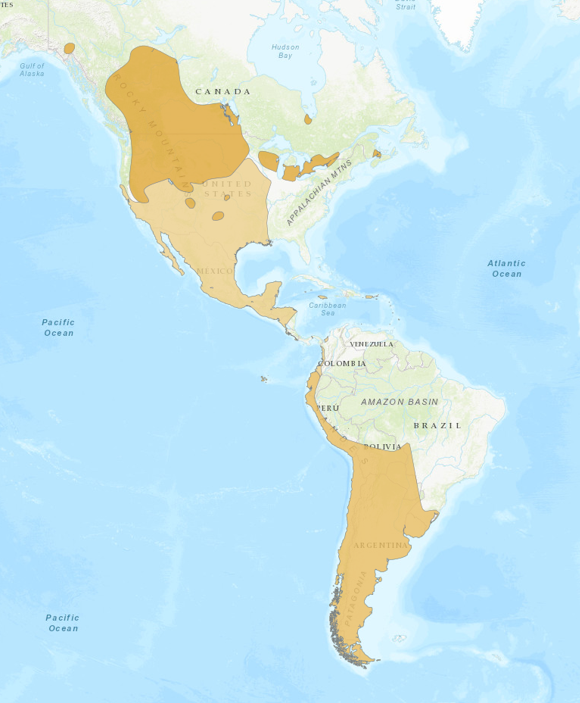

Breeds in central and western North America. Winters in western and southern South America.

Breeding. Breeds from late May to July around ponds and lakes with marshy borders and other wetland complexes that combine marshes and open water, mainly in the Great Plains and Great Basin from northern Alberta and central British Columbia south to eastern California and the Texas Panhandle. Also locally—perhaps only sporadically—north to the Yukon and Northwest Territories (Great Slave Lake region), and east to James Bay and the Great Lakes region.

Nonbreeding. Winters from October to April in ponds and marshes along the Pacific coast from Colombia to Tierra del Fuego, in Andean lakes from Ecuador south, and on the pampas of Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil—where rare but likely regular northeast to Rio de Janeiro—and south throughout Patagonia.

A few stragglers sometimes winter far north of the usual range: e.g., in Mexico, Panama, and occasionally north to California and Texas.

Movements. Northbound migration is compressed, mostly within April and May. Most migrants apparently follow the Pacific coastal plain to around the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, then fan out with some continuing along the Pacific, some moving across the central plateau, some following the Gulf coastal plain, including the Yucatán Peninsula.

Regularly overshoots to Alaska and the Canadian arctic in May and June.

Southbound migration is protracted, beginning as early as June with the departure of females almost immediately after laying their eggs. Males and juveniles depart the breeding grounds over the course of July and August.

Substantial post-breeding dispersal westward to coastal areas of the Pacific Northwest, from British Columbia south.

Breeding Bird Survey Abundance Map. U.S. Geological Survey 2015

A smaller portion of post-breeders disperse across eastern North America, regularly appearing at many sites along the Eastern Seaboard from Newfoundland south, along the Gulf Coast, and at various interior ponds and lakes from the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley south.

Small numbers of fall migrants are detected in the West Indies—mostly in Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles, which indicates that they are probably disoriented individuals that wandered far offshore, then chanced upon a fortunate landfall. Small numbers also appear annually in the Galápagos, presumably for similar reasons. Semi-regular but not quite annual in Hawaii.

Annual as a transatlantic vagrant in western Europe—especially the British Isles and Iberian Peninsula—as well as Bermuda and Macaronesia. There are at least a few records from almost every part of Europe and adjacent Mediterranean coasts.

Its penchant for vagrancy sometimes takes it farther afield. There are records from the Falkland Islands, the Pribilofs, Wrangel Island, Yakutia, South Korea, Japan, Guam, New Zealand, Australia, Gabon, Namibia, South Africa, the U.A.E., and Oman. An exceptional individual found dead on Alexander Island near Antarctica in October 1968 is among the most southerly records of any shorebird.

Identification

The largest and most terrestrial of the three phalaropes—though still partly aquatic—also peculiar in structure and behavior.

Visually similar in all plumages to the more widespread Red-necked Phalarope (see below), but differs in several details. Wilson’s is much larger, has a proportionately long, black bill, and lanky, ungainly structure, with a long neck, small head, and large, pot-bellied body.

Wilson’s is one of the few shorebirds that can often be identified by behavior alone. When foraging on land, it pursues prey by running frenetically, usually with its head down and its tail up. In the water, it often swims in a similar fashion, riding low in the water and chasing flies at the surface.

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Big Lake, Molt, Montana; May 29, 2020.) © Jan Thom

Like other phalaropes, Wilson’s reverses the usual sex roles: females are larger and more colorful than males, and depart immediately after laying the eggs.

Female in breeding plumage has a black mask that continues down the side of its neck, where it is bordered by a brick-red patch toward the shoulder and a salmon-pink wash on the front of the neck. The female also has a brick-red streak on the scapulars.

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Nicolet Bird Sanctuary, Baie-du-Febvre, Quebec; May 15, 2017.) © André Lanouette

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Lewisville Lake Park, Lewisville, Texas; May 21, 2017.) © Katherine Cavazos

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Estero Llano Grande State Park, Texas; April 28, 2018.) © James Hoagland

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (New Haven, Macomb County, Michigan; June 11, 2017.) © Brendan Klick

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage—an exceptionally pale individual. (Hebron Fish Hatchery and Wetlands, Licking County, Ohio; April 28, 2019.) © Brad Imhoff

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Lewisville Lake Park, Lewisville, Texas; May 21, 2017.) © Katherine Cavazos

Wilson’s Phalarope, dorsal view of female in breeding plumage, showing reddish streaks on back. (Lewisville Lake Park, Lewisville, Texas; May 21, 2017.) © Katherine Cavazos

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Lehi, Utah; May 2, 2014.) © Matthew Pendleton

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Chico Basin Ranch, Pueblo County, Colorado; May 1, 2013.) © Bill Maynard

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (University at Buffalo – North Campus, Getzville, New York; June 17, 2014.) © Jim Pawlicki

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage, showing an atypically dark—blackish—crown. (Lee Creek, Salt Lake County, Utah; June 20, 2020.) © Max Malmquist

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, Sacramento, California; June 25, 2015.) © Matt Davis

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage, showing salmon-pink blush on front of neck and chest. (Tommy Thompson Park, Toronto, Ontario; May 12, 2020.) © Jonathan Chu

Wilson’s Phalarope, dorsal view of female in breeding plumage, showing reddish streaks on back. (IRWD San Joaquin Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary, Irvine, California; June 24, 2017.) © Don Hoechlin

Wilson’s Phalarope, female (foreground) and male in breeding plumage. (IRWD San Joaquin Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary, Irvine, California; June 24, 2017.) © Don Hoechlin

Male in breeding plumage looks like a washed-out version of the female, but in addition to being duller it has a slightly different pattern—sometimes showing rusty fringes throughout its upperparts, but usually lacking the female’s concentrated reddish streaks.

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage. (New Haven, Macomb County, Michigan; June 11, 2017.) © Brendan Klick

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage—more vividly colored than most. (Burns, Oregon; May 25, 2007.) © Greg Gillson

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage. (Salton Sea, California; June 21, 2020.) © Sharif Uddin

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in faded breeding plumage. (Mono Lake – South Tufa Area, California; July 13, 2019.) © Matt Davis

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage. (Summer Lake, Oregon; June 9, 2018.) © Eric VanderWerf

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage. (Lee Creek, Salt Lake County, Utah; June 20, 2020.) © Max Malmquist

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage. (Lee Creek, Salt Lake County, Utah; June 20, 2020.) © Max Malmquist

Wilson’s Phalarope, male entering breeding plumage. (Riparian Preserve at Gilbert Water Ranch, Gilbert, Arizona; May 7, 2018.) © Sean Fitzgerald

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in unusually pale breeding plumage. (Clinton, Maine; May 16, 2017.) © Josh Fecteau

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in faded breeding plumage. (Walden Reservoir, Jackson County, Colorado; July 8, 2019.) © Charles Hundertmark

Adults in nonbreeding plumage are generally pale-gray above and can be distinguished from other species in flight by three features: an all-white rump, pale-gray (sometimes whitish) tail, and unmarked wing (i.e., no wing-stripe).

Leg color changes during the life-cycle: black in breeding adults and variably yellow, orange, or greenish in nonbreeding adults and immatures.

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in nonbreeding plumage. (Moss Landing Wildlife Area, California; August 16, 2018.) © Steve Kelling

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage. (Port Aransas Nature Preserve, Port Aransas, Texas; October 27, 2016.) © Ruth Danella

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage. (Punta del Chileno, Maldonado, Uruguay; August 24, 2020.) © Joaquin Muñoz

Wilson’s Phalarope, female showing vestiges of breeding plumage. (Mono Lake – South Tufa Area, California; July 13, 2019.) © Matt Davis

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage, showing unmarked wing and white rump. (San Clemente Island, California; July 30, 2018.) © Nicole Desnoyers

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage. (Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, New York; September 17, 2017.) © Ken Feustel

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage, showing pale-gray tail. (Parc Le Jardin des Souches, Montmagny, Quebec; September 16, 2020.) © Mathieu Binet

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage. (Craigton, Ohio; September 11, 2019.) © Don Danko

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage. (Glendale, Arizona; August 2, 2020.) © Pierre Deviche

Wilson’s Phalarope, nonbreeding plumage. (Glendale, Arizona; August 2, 2020.) © Pierre Deviche

Immatures generally resemble nonbreeding adults, but go through a briefly-held juvenile plumage that is warm-brown and buffy.

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile. (Robert Lake, Kelowna, British Columbia; August 3, 2020.) © Kalin Ocaña

Wilson’s Phalarope, typical juvenile plumage. (Pointe Mouillee State Game Area, Michigan; August 29, 2013.) © Darlene Friedman

Wilson’s Phalarope, unusually warm rusty and buffy juvenile plumage. (Port Susan Bay TNC Reserve, Snohomish County, Washington; July 26, 2008.) © Steven Mlodinow

Wilson’s Phalarope, typical juvenile plumage. (Ashbridge’s Bay Park, Toronto, Ontario; July 17, 2018.) © Jean Iron

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile molting into nonbreeding plumage, showing large, lobed, yellow-orange feet. (Aéroport Pôle Caraïbe, Guadeloupe; October 10, 2017.) © Anthony Levesque

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile molting into nonbreeding plumage —note peculiar small-headed, long-billed, pot-bellied structure. (Prewitt Reservoir, Colorado; July 22, 2020.) © Caleb Alons

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile. (Glendale, Arizona; August 2, 2020.) © Pierre Deviche

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile—note peculiar small-headed, long-billed, pot-bellied structure. (East Sullivan, La Vallée-de-l’Or, Quebec; August 26, 2017.) © Raymond Ladurantaye

Wilson’s Phalarope, typical juvenile plumage. (Redmond Sewage Ponds, Deschutes County, Oregon; July 4, 2019.) © Charles Gates

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile molting into nonbreeding plumage. (Point Park, Riverview, New Brunswick; August 23, 2019.) © Jim Carroll

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile molting into nonbreeding plumage. (Ensley Bottoms, Memphis, Tennessee; September 13, 2014.) © Michael Todd

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile molting into nonbreeding plumage. (Ensley Bottoms, Memphis, Tennessee; September 13, 2014.) © Michael Todd

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage. (Meadow Springs, Colorado; July 23, 2019.) © Andy Bankert

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage, showing unmarked wing, white rump, and mostly pale-gray tail. (Amherst Island, Ontario; May 17, 2019.) © Jean Hebert

Wilson’s Phalarope, showing white rump and mostly pale-gray tail. (Antelope Island State Park, Churchill County, Utah; August 16, 2020.) © Max Malmquist

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage. (Fox Lake, Wisconsin; June 16, 2006.) © Jack & Holli Bartholmai

Wilson’s Phalarope, female in breeding plumage, showing unmarked wing, white rump, and mostly pale-gray tail. (Horicon National Wildlife Refuge, Wisconsin; June 29, 2020.) © Victor Chen

Wilson’s Phalarope, male in breeding plumage, showing unmarked wing, white rump, and mostly pale-gray tail. (Kelly Prairie, Morrow County, Oregon; July 15, 2017.) © Russ Morgan

Wilson’s Phalarope, male surfing on female. (Mitchell Lake Audubon Center, San Antonio, Texas; May 2, 2018.) © Robert Michaelson

Wilson’s Phalarope, juvenile molting into nonbreeding plumage, exhibiting one its distinctive feeding behaviors, chasing flies. (Ensley Bottoms, Memphis, Tennessee; September 13, 2014.) © Michael Todd

Wilson’s Phalarope, exhibiting one of its distinctive feeding strategies: stealthy fly-stalking. (Antelope Island State Park, Utah; August 16, 2020.) © Max Malmquist

Wilson’s Phalarope, exhibiting one of its distinctive feeding strategies: stealthy fly-stalking. (Antelope Island State Park, Utah; August 16, 2020.) © Max Malmquist

Cf. Red-necked Phalarope. Red-necked and Wilson’s Phalaropes occur together during migration and are similar enough to be confusing under some circumstances—especially the breeding male plumages, in which both species have a somewhat blurred blend of rust, gray, and white on their necks.

The key differences, which hold true in all plumages, are size, bill length, wing pattern, and rump pattern. Wilson’s is substantially larger and proportionately longer-billed, and has a plain, unmarked wing, and an all-white rump, whereas Red-necked has a whitish wing-stripe and divided rump: blackish in the middle and white on the sides.

In nonbreeding plumages, Red-necked and Wilson’s also differ in head pattern. Red-necked has a blackish mask that extends to the ear-coverts, whereas Wilson’s has a faint, pale-grayish mask that extends down the neck.

Notes

Monotypic species. Sometimes assigned to its own monotypic genus Steganopus.

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

Ascanio, D., G.A. Rodriguez, and R. Restall. 2017. Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London.

BirdLife International. 2016. Steganopus tricolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22693472A93409634. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693472A93409634.en. (Accessed November 6, 2020.)

de la Peña, M.R., and M. Rumboll. 1998. Birds of Southern South America and Antarctica. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2020. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed November 6, 2020.)

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2011. Field Guide to the Birds of Macaronesia: Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

Jaramillo, A. 2003. Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Marchant, J., T. Prater, and P. Hayman. 1986. Shorebirds: An Identification Guide to the Waders of the World. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Raffaele, H., J. Wiley, O. Garrido, A. Keith, and J. Raffaele. 1998. A Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. Princeton University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Salt, W.R., and J.R. Salt. 1976. The Birds of Alberta. Hurtig Publishers, Edmonton, Alberta.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Sinclair, I., P. Hockey, W. Tarboton, and P. Ryan. 2011. Birds of Southern Africa (Fourth Edition). Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd. Cape Town, South Africa.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wells, J.V., and A.C. Wells. 2017. Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Cornell University Press.

Wikiaves. 2020. Pisa-n’água, https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/pisa-n_agua. (Accessed November 6, 2020.)