Woody Herman led big bands for a half-century, but in the beginning it seemed unlikely he would last more than a year or so. Herman spent his first years as a bandleader struggling to find both an audience and a distinctive musical style. Yet the early Herman orchestra was one of the better bands of the late 1930s and early 40s and had a special affinity for the blues.

This week on SDPB Radio’s Big Band Spotlight we’ll hear a few highlights from Herman’s often overlooked “Band That Plays the Blues.”

The beginnings of Woody Herman’s long career as a bandleader date to 1936 when he was playing saxophone and clarinet and singing in Isham Jones’ popular dance orchestra. After some two decades in the band business, Jones was ready to hang up his baton and retire from music. He was only 40 years old, but songwriting royalties from such popular songs as “It Had to Be You,” “Swingin’ Down the Lane,” “There is No Greater Love” made him a wealthy man. A group of the more jazz-oriented musicians from the Jones’ orchestra decided to form their own group and chose Herman as the leader. Even though he was the youngest at 23, Herman had been in show business the longest, having started as a nine-year-old singing, dancing and playing saxophone in Milwaukee and Chicago vaudeville houses.

The new Herman band was a co-operative unit with each member owning a share of the group, which meant every decision was made by committee. They rehearsed for several weeks while wondering if they were ever going to land a job. Finally on Election Day, November 3, 1936, as Franklin Roosevelt was defeating Alf Landon in a landslide, the band opened at the Brooklyn Roseland Ballroom (not to be confused with the more famous Roseland in Manhattan). The young Herman orchestra got a record deal with the Decca label and started cutting sides a few days later. Although the band wanted to play jazz, their first half-dozen records were mostly tame, forgettable, sweet-styled numbers featuring Herman’s friendly vocals.

The Herman band was a hit at the Roseland Ballroom in Brooklyn and moved up to Manhattan’s Roseland. For a while they played opposite an unknown band from Kansas City: Count Basie’s. Herman’s drummer Frank Carlson watched and listened closely to the loose and free approach of Basies’ great drummer Jo Jones, and that influence helped give the Herman band a lighter rhythmic feel than most swing bands of the day. Herman and the Count became friends for life and both led bands well into the 1980s.

Even though they were “The Band That Plays the Blues,” Herman recalled that they had to fight to play them at the Roseland. The management wanted mostly fox trots, waltzes and rumbas to keep the dancers happy. According to big band writer and historian George T. Simon, Herman told the manager to get lost and quit bothering him. But he was so good-natured yet so firm and positive that the manager not only took it but also became one of the band’s biggest fans.

Despite its billing, this Herman band played more than the blues. Their book was filled with romantic ballads, novelty numbers, dance tunes and Dixieland-style instrumentals reminiscent of the Bob Crosby Orchestra. But this meant the band didn’t really have a distinctive personality. It didn’t help that the group’s role at Decca Records was as something like the label’s unofficial house band. It cranked out covers of other group’s hit and backed up Decca’s singers, including Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Mary Martin, Connie Boswell, the Andrews Sisters and others.

In the fall of 1938 the Herman band turned two years old, but was still struggling. The musicians were so short of cash that one night while they were playing at a hotel in Cincinnati, they pooled their money and sent violinist Nick Hupfer across the river to Kentucky where there was gambling to win at poker. But he didn’t do too well and the musicians ended up worse off than they were before.

In the fall of 1938 the Herman band turned two years old, but was still struggling. The musicians were so short of cash that one night while they were playing at a hotel in Cincinnati, they pooled their money and sent violinist Nick Hupfer across the river to Kentucky where there was gambling to win at poker. But he didn’t do too well and the musicians ended up worse off than they were before.

Nevertheless, the band was getting good press with magazine writers predicting the band was about to make it big. On April 12, 1939 Herman and his band went into the Decca studios and at the last minute waxed a simple blues that had evolved on the bandstand back at the Brooklyn Roseland Ballroom over two years earlier. This was “Woodchoppers’ Ball” and it became by far Herman’s biggest hit. For the next forty-five years, Herman had to play the tune nearly every night. Understandably, he grew to hate it. Herman once said of “Woodchopper’s Ball”: “It was great, the first thousand times we played it.”

The record would ultimately sell a reported five million copies, but it took a few years before it became a hit. In the meantime, the band’s struggles continued and so did face-offs with ballroom and theater managers who demanded softer, commercial dance music.

Perhaps the biggest hindrance to the Herman orchestra’s efforts in establishing a stronger musical personality and public presence was its organization as a co-operative band. Although being a co-op created a strong esprit de corps, because each musician owned a share in the band, every decision required a meeting and a vote – often in men’s rooms. According to Herman biographer Gene Lees, even wives of the musicians had something to say about many minor matters, such as travel arrangements. It also proved difficult to get rid of musicians who weren’t working out. Bookings and record dates were sometimes messed up and opportunities missed.

But in the fall of 1941 the band recorded “Blues in the Night” and it became an immediate hit, unlike “Woodchoppers’ Ball.” It was also the only Herman record to reach the top the charts. Finally after five years of scuffling, the Herman orchestra was becoming a popular name band. “Suddenly we got hot,” Herman said. “We played like we always had, but the customers suddenly began to act like they liked it.” Drummer Frank Carlson, one of the original members of the band, recalled that everywhere they played people screamed in appreciation.

“The Band That Plays the Blues,” like all the other bands during World War Two, lost musicians to the military draft. However this gave Herman the opportunity he needed to take command of the orchestra. Herman was exempted from the draft because of a second hernia and as each member was drafted he bought his stock until eventually he had it all and complete authority.

Although Herman claimed the band was just playing like it always had, there was a new energy and sound as the band moved from Dixie-styled swing to a much more modern approach. Records like 1941’s “Woodsheddin’ with Woody” and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Down Under” from 1942 signaled the band’s change in direction. (Herman was so impressed by Gillespie’s arranging that he advised him to give up the horn and stick to writing. “Thank God he ignored me,” Herman said later.)

Those records also marked the beginning of the end of Herman’s “Band That Plays the Blues.” By November 1944 Herman was the only one left from the group that debuted at Brooklyn’s Roseland Ballroom eight years earlier. No longer a cooperative group, Herman was in complete control and soon he’d soon startle the music world with a spirited, adventurous and modern orchestra that was not only very popular, but also one of the greatest big bands in jazz history. This was the band given the rather inaccurate nickname “The First Herd.”

Because of the greatness of the bands that followed, Herman’s first group is usually given short shrift. It might not have been the most inventive and distinctive band of the Swing Era, but few could match its impeccable musicianship and easygoing swing.

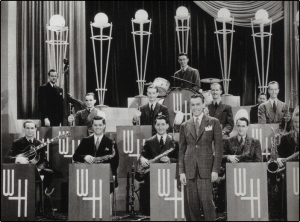

“The Band That Plays the Blues” made a Warner Brothers Vitaphone short in 1938 that included this performance of “Carolina in the Morning.” (The audience was clumsily edited into the short and they look woefully out of place.)

Also from the 1938 short is this Herman performance of an old King Oliver number, “Doctor Jazz.”