Ptiloris

Magnificent Riflebird by Eric Gropp, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: Feather Nostrils

First Described By: Swainson, 1825

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Eupasseres, Passeri, Euoscines, Corvides, Corvoidea, Paradisaeidae

Referred Species: P. magnificus (Magnificent Riflebird), P. intercedens (Growling Riflebird), P. paradiseus (Paradise Riflebird), P. victoriae (Victoria’s Riflebird)

Status: Extant, Least Concern

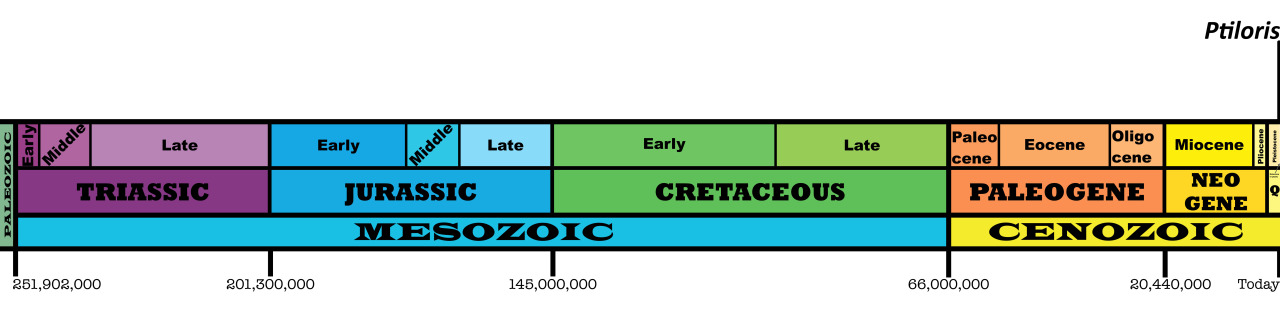

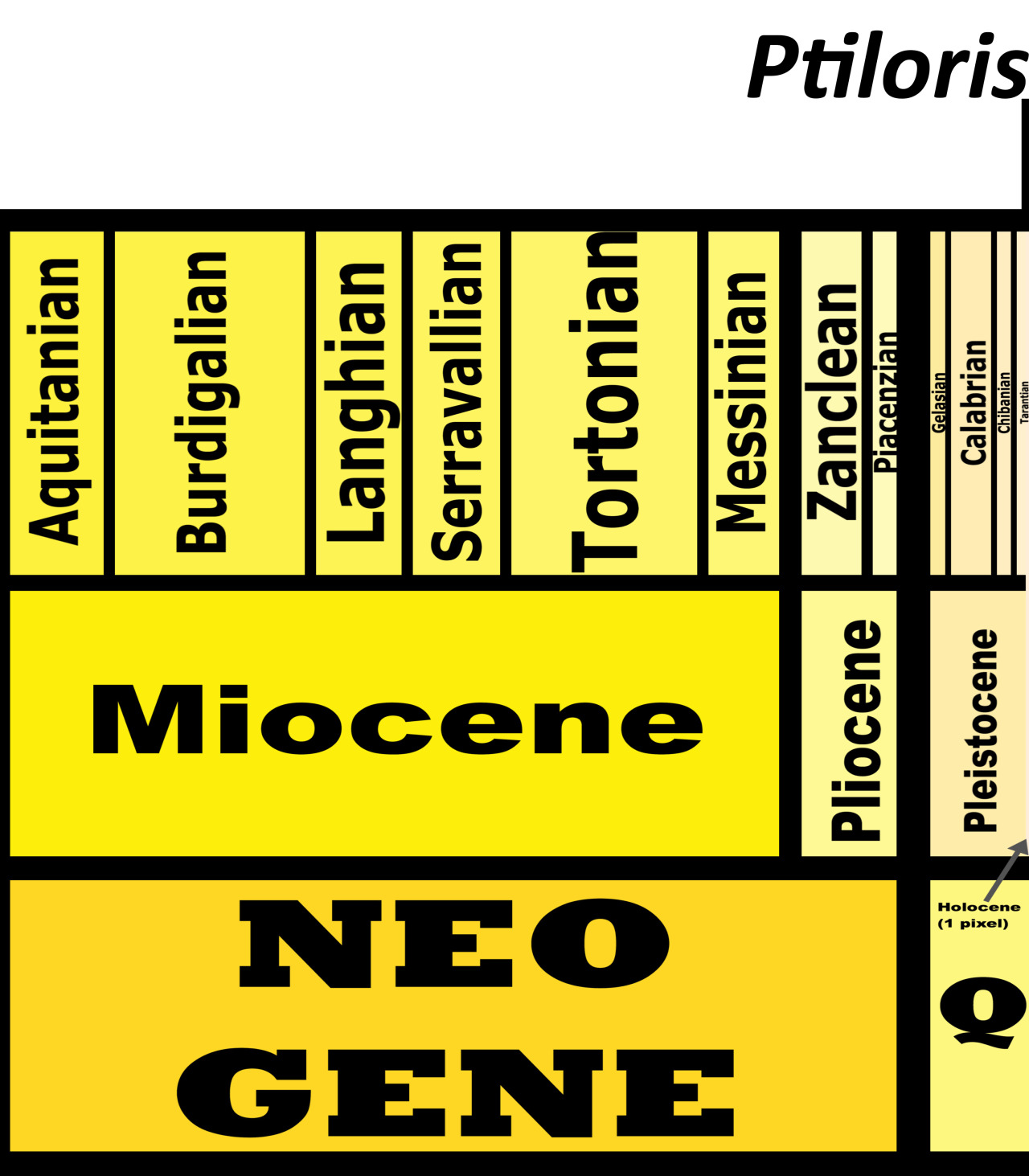

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Riflebirds are known from Papua New Guinea and Australia

Physical Description: The Riflebirds are Birds of Paradise - extremely beautiful and weirdly patterned birds with distinctively colored males and fairly drab females, so different that it is not unreasonable to think they’re different birds. In this case, the Riflebird females are a chestnut brown color on their backs, wings, and tails; with brown and white stripes on their heads. They also have white and brown striping across their bellies and bellies and breasts. This is the same for three of the four species - distinctively enough, the females of Victoria’s Riflebird look different still, with more grey feathers on the back, tail, and head; and beige bellies with brown spots. The females are invariably smaller than the males - at 23 - 29 centimeters in length.

Paradise Riflebird by Dominic Sherony, CC BY-SA 2.0

The males, meanwhile, are ridiculous. At 25 - 34 centimeters in length, they are, on average, much larger than the females, and very large perching birds overall. They are generally black in color, with blue-green patches all over their bodies. These patches occur on the tops of their heads, the undersides of their necks, and across their tails, varying a little from species to species, and generally very iridescent and beautiful to look at. They have very large, black wings, that are able to spread out into amazing displays - displays for sex! More on the specifics of the display in the Behavior section, but for now, it’s important to note what these birds can look like. They often raise up their wings during these displays, making a crescent of black shiny feathers. They then can fold out the wings and their tails, leaving two white spots in a sea of black, over a long strip of turquoise feathers - the famed Weird Bird Mating Display of nature documentary fame.

Victoria’s Riflebird by Joseph C. Boone, CC BY-SA 4.0

Both sexes are long in body, with long tails and heavy wings. They have small heads and compact necks. Their bills are very long, grey, and curved. They have long, thin grey legs as well. In short, even if these things weren’t distinctive in their color and behavior, they would be very distinctive in their overall body shape!

Diet: The Riflebird feeds primarily on both fruits and small to medium sized animals, including insects, spiders, centipedes, and even flower nectar from time to time. Some species feed more on fruits than on insects, while others are the reverse.

Growling Riflebird by Markus Lilje

Behavior: Riflebirds spend almost all of their time foraging alone or in pairs, though they do sometimes form groups or even mixed-species foraging flocks. They search for fruit in the upper canopy, but look for insects in the lower canopy, moving back and forth between rainforest levels looking for different sources of food. They especially like going to trees such as Pandan trees that have extensive fruit and insects. They will probe along the branches, pecking at bark and investigating holes with their huge beaks to get food. They move quickly through the jungle, making sure to not stay in any one spot for too long. As they move about the forest, tney make “hrrak-hrrow-hrrak-hrrow” calls back and forth. Some species do make more “woiieeet-woit” calls instead. They can be aggressive to one another, making “kek-kek-kek-kek” calls. Parents will make soft “kuk” calls to their children on the rim of the nest. To attract females, males will literally go “Yaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaas” loudly in the jungle, which I just think ups their meme potential to maximum levels. These calls can be very loud, reaching up to 1 kilometer away. These birds don’t migrate based on food availability, though sometimes males will move out of rainforests into adjacent woodlands during the winter.

The Riflebirds have the most famous mating display of any bird, honestly, popularized by such things as nature documentaries. The male will first advertise loudly throughout the forest, dispersed greatly from one another but not necessarily enforcing mating territories. First, the male will erect his throat patch and the bright feathers on the sides to catch the sunlight and show off the coloration. Then, he curves his rounded wings above his body, tilting his head back and forth to expose the throat color to the light even more. He then moves back and forth from side to side. They then open their bills, showing a bright yellow mouth, still while moving from side to side. Finally, the males will flatten out their wings, creating a flat surface that looks like a blue screaming mouth on a black background. He then hops back and forth around the female. If the female is happy with this display, she will reward him with multiple matings; the female then leaves to build her nest, while the male tries to woo more females.

Victoria’s Riflebird by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

The female then goes to make a nest out of a raggedy cup made of sticks, supported by branches near the trunk of the tree. They are usually supported with fibres and dry leaves to form wires around the cup. The clutches are usually 1 to 3 eggs and are well guarded, to the point that the incubation and nestling periods of the eggs isn’t well known. In Victoria’s Riflebird, at least, the eggs are incubated for nearly three weeks; the female then feeds and rears the chicks for about two to three weeks before fledging and leaving the nest, sticking with the mother for a little while before going off on their own. Male Riflebirds have been known to live up to 15 years in the wild.

Ecosystem: The Riflebirds live primarily in subtropical and temperate rainforests, as well as adjacent dry forests. They’re usually found in mid-level elevations - not on high mountains, not above 1200 meters, but also not below 200 meters except in some cases of being near sea level in species such as the Victoria’s Riflebird. They do sometimes visit mangroves swamps and selectively logged forests.

Victoria’s Riflebirds by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: The Riflebirds are not globally threatened, and while they can be uncommon in certain locations, they are overall commonly found in a variety of habitats. Even so, their preferred ecosystems are, in general, threatened by climate change, making Riflebirds a unique species in need of protection regardless.

Species Differences: The Riflebirds are primarily allopatrically separated - they look similar and behave similarly, but all occupy different locations. The Magnificent Riflebird lives throughout most of Papua New Guinea apart from the most eastern tip, and the tip of the Cape York Peninsula. The Growling Riflebird lives on the eastern parts of Papua New Guinea, where the Magnificent Riflebird isn’t found. Victoria’s Riflebird is known from the eastern coast of the Cape York Peninsula. Finally, the Paradise Riflebird is known from the eastern coast of mainland Australia.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

del Hoyo, J., Collar, N. & Christie, D.A. (2019). Growling Riflebird (Lophorina intercedens). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Frith, C., Frith, D. & Christie, D.A. (2019). Magnificent Riflebird (Lophorina magnifica). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Frith, C. & Frith, D. (2019). Paradise Riflebird (Lophorina paradisea). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Frith, C. & Frith, D. (2019). Victoria’s Riflebird (Lophorina victoriae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.